College Readiness Indicator Systems Framework

A new framework from the CRIS initiative provides guidance for schools and districts to implement a system of indicators and supports for students who are off track for post-secondary success.

The authors wish to thank their colleagues at the three CRIS research partner organizations for their helpful comments on this article.

More students than ever are enrolling in college after high school, but concerns are growing among policymakers, educational leaders, the business community, and other stakeholders because many of them are not college ready, as evidenced by low rates of college completion (Turner 2004). The sense of urgency to close the gap between college eligibility and college success has been captured by the Common Core State Standards, explicitly designed to reflect “the knowledge and skills that our young people need for success in college and careers.”1

In the face of the higher expectations embedded in the new standards, districts must look beyond the goal of high school graduation to ensure that their students graduate ready for college and career. To that end, an important task is to link information about the performance of high school students to their post-secondary enrollment and degree attainment, and districts increasingly have access to data that allows them to do just that. The wealth of information now available creates an unprecedented opportunity for district administrators, educators, and community partners to monitor and support students in attaining their educational aspirations.

However, the ready availability of data is just a starting point. Increasing college readiness and success rates among students, particularly historically underrepresented students, will require ways to measure college readiness that go beyond test scores and grades. It will require indicator systems that identify students who fall off track and assess the effectiveness of the supports and interventions used in response. It will also require fostering a culture of data inquiry in schools and school systems and building the capacity of administrators, educators, and community partners to effectively use data in supporting students.

However, the ready availability of data is just a starting point. Increasing college readiness and success rates among students, particularly historically underrepresented students, will require ways to measure college readiness that go beyond test scores and grades. It will require indicator systems that identify students who fall off track and assess the effectiveness of the supports and interventions used in response. It will also require fostering a culture of data inquiry in schools and school systems and building the capacity of administrators, educators, and community partners to effectively use data in supporting students.

Furthermore, education stakeholders need a framework to link a vision for college readiness to specific and multidimensional constructs of readiness, measurable and valid indicators, data use, and supports and interventions. As partners in the College Readiness Indicator Systems (CRIS) initiative, the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, the John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities at Stanford University, and the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research have worked with four urban districts and one school support network to develop and study the implementation of a system of indicators and supports designed to significantly increase students’ readiness to enter and succeed in college.2 This collaborative work has helped deepen our understanding of the interconnect- ed elements and strategies necessary for an effective college readiness indicator system, which we describe in this article as the CRIS framework.

The CRIS framework is meant to provide guidance to district administrators, community partners, and educators in building and implement- ing an indicator system that monitors students and guides the allocation of supports and resources to ensure that more students finish high school ready to be successful in college and career. The work of building this system in response to new national college readiness expectations is still in an early stage, and in that spirit we will share promising strategies emerging from the experiences of the CRIS sites in several CRIS tools and resources, now in development, which will be available in 2014.

The CRIS framework: A systematic approach to keeping students on track for college readiness

Many school systems already have in place “early warning systems” to keep their students on track to high school graduation.3 The CRIS framework builds upon and enhances existing early warning systems in several ways.

First, CRIS looks beyond high school graduation and college eligibility to target college readiness. Moreover, most monitoring systems currently in use focus on academic preparation, as defined by a limited number of academic measures such as course credit and grade point average. But educators are increasingly aware that academic content alone is not enough to ensure success. CRIS conceptualizes college readiness not just as academic preparation but also as the knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes necessary to access college and be successful once in college.4

Second, the CRIS framework recognizes that indicators are needed at three levels: individual (student), setting (school), and system (district). Individual-level indicators help identify students who need support. Setting- and system-level indicators serve to monitor whether the conditions are in place to promote college readiness and inform decision-making (e.g., allocation of resources; design of new policies) when those conditions are not met.

Finally, CRIS recognizes that the responsibility for making college readiness supports available goes beyond the district. The CRIS indicators and their respective cycles of inquiry can serve to mobilize efforts by the district and its community partners to establish a citywide network of college readiness supports directly aligned with the needs identified in the student population. Indicators and cycles of inquiry also serve to monitor the effectiveness of those supports. In this way, CRIS affords flexibility and attention to local variation in needs, capacity, and opportunities and guides use of resources available in the community to provide the supports and interventions that prove to be most effective for college readiness.

Framework components

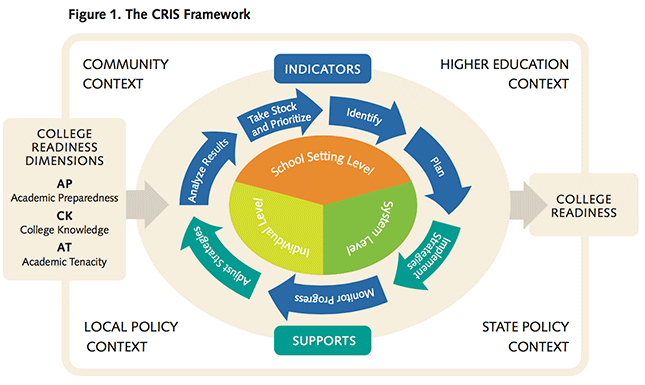

The CRIS framework, depicted in Figure 1, provides a conceptual foundation for the development and implementation of college readiness indicator systems.

Dimensions of College Readiness: Beyond Academic Preparedness

Implicit in the framework is an understanding of college readiness as multifaceted, encompassing not just academic preparation but also the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors necessary to access college and overcome obstacles on the road to post-secondary success. Accordingly, the CRIS framework features indicators to target three distinct yet interdependent college readiness dimensions: academic preparedness, college knowledge, and academic tenacity.

- Academic preparedness refers to key academic content knowledge and cognitive strategies needed to succeed in doing college-level work. Examples of indicators of academic preparedness are GPA and availability of Advanced Placement courses.

- Academic tenacity refers to the underlying beliefs and attitudes that drive student achievement. Attendance and disciplinary infractions are often used as proxies for academic tenacity; other indicators include student self-discipline and the extent to which teachers press students for effort and rigor.

- College knowledge is the knowledge base and contextual skills that enable students to successfully access and navigate college. Examples of college knowledge indicators are students’ knowledge of the financial requirements for college and high schools’ promotion of a college-going culture.

Students, Schools, and Systems: A Tri-level Approach

Another unique feature of the CRIS framework is its tri-level approach premised on the idea that solely considering indicators of student-level outcomes does not suffice to fully understand how to promote college readiness. The tri-level perspective posits that the consideration of context is critical to monitor whether the conditions (i.e., resources, practices, policies) are in place to promote college readiness and to inform how to correct action when they are not. A comprehensive indicator system thus includes:

- At the individual level, indicators measure students’ personal progress toward college readiness. In addition to courses and credits, individual-level indicators include knowledge about college requirements and students’ goals for learning.

- At the setting level, indicators track the resources and opportunities for students provided by their school. These include teachers’ efforts to push students to high levels of academic performance, a high school’s college-going culture, and availability of Advanced Placement courses.

- At the system level, the focus of the indicators is on district policy and funding infrastructure that impact the availability of college readiness supports, including guidance counselors, professional development for teachers, and resources to support effective data generation and use. System-level indicators are crucial in that they signal the extent to which district-level resources are in place to carry out an effective college readiness agenda.

The three dimensions of college readiness, when combined with the three levels, give rise to a 3 x 3 matrix that we call the “CRIS Menu.” The indicators in the CRIS menu reflect an extensive review of the research literature on high school factors that predict college readiness. By selecting indicators from the CRIS menu that are directly relevant to their own context, districts construct an indicator system that is evidence-based and attuned to their unique goals and priorities.5

Tying the Indicators to Supports

In addition to indicators, organized into three dimensions and three levels, the CRIS framework features college readiness supports. These refer to programs or activities that are enacted in order to effect some intended change in performance, behavior, or environment. In some cases, supports target students (e.g., tutoring program; workshop on how to complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA) and in others they target adults (e.g., availability of a data coach who can facilitate staff conversations about data; professional development for teachers around college readiness).

The cycle of inquiry process, depicted as the consecutive circular arrows in Figure 1, is the mechanism that connects indicators with supports. The cycle of inquiry serves to:

- guide the process of identifying students (the individual level) who need help and connecting them with the appropriate supports (e.g., tutoring, counseling, etc.);

- enable stakeholders to examine whether resources are available (e.g., data infrastructure, professional development for teachers) and policies in place (e.g., consistent attendance policy) at the setting (school) and system (district) levels to promote college readiness;

- help leadership establish effective processes and structures for using indicators.

Ultimately, close monitoring of indicators and timely action as appropriate will increase the chances that more students attain the combination of skills, knowledge, and attitudes needed by the time they finish high school in order to access college and succeed once they are in college.

The process of using indicators to monitor progress toward college readiness and to activate supports and interventions when needed is embedded in the community, policy, and higher education context, represented by the larger background rectangle. The context captures outer conditions that impact – positively or negatively – the ability of students to be college ready. These include the current state and local education policy around college readiness (e.g., high school graduation requirements; availability, accessibility, and affordability of higher education) and the extent of collaboration across multiple sectors of the community (including those that interact with the district) to build college readiness partnerships, share data, and establish mutual priorities to support college readiness.

Some of these contextual conditions are within the locus of control of district leaders; some are not. Either way, they influence how college readiness is defined, developed, and deployed in a school district. Combined with system-level indicators, the context shapes how effectively CRIS can be implemented, who is involved in it, and what kinds of resources and supports are available to them.

Building a college readiness indicator system

The process of building a CRIS involves much more than a district selecting indicators from the CRIS Menu that are directly relevant to its strategic mission and current priorities. A successful CRIS district will carefully plan the timeline for data collection and analysis, assess and respond to data infrastructure needs, and assign staff roles and responsibilities associated with indicators. In other words, the district maps the conditions for each indicator that will allow for its systematic and effective use. This process may sound simple in theory but it is challenging in practice. Its importance, however, cannot be overstated.

This close examination of a given indicator also allows for the identification of potential challenges and bottlenecks when it comes to actually using the indicator to inform action, including human resistance to change and internal politics, and taking proactive steps to handle those effectively. Concerns may also be uncovered about the quality of the currently available data (e.g., the way in which student attendance is collected varies across schools) or about capacity issues around collecting and understanding data (e.g., training is needed to bring teachers up to speed with a new student information system). Similarly, system strengths may be identified that support the transition from data to action, such as a districtwide culture of data use that is already in place.

Ultimately, the challenge of developing an effective CRIS involves more than the presence or absence of valid, reliable, relevant indicators. It requires attention to issues of data use – how to support action – which, if not addressed up front, are bound to jeopardize CRIS efforts. It also requires examination of the supports that adults in the system need in order to collect, use, and act on data. Administrators and teachers need time to reflect on the meaning of data and to know what questions their data can and cannot answer or how to interpret complex relationships in the data. The users – administrators, board members, teachers, parents, students – of the CRIS must be involved in its development and implementation. This involvement will likely facilitate the emergence of a common language and common set of goals around college readiness, ensure buy-in, and also increase the chances that the end product meets users’ needs and will be sustained and deepened.

Using a college readiness indicator system: The cycle of inquiry

Building a culture within organizations around data use depends on having a process for data inquiry that guides how data are used and the adoption of supports and policies around college readiness. The cycle of inquiry illustrates what data use looks like in action and helps guide what components are needed for an effective data system.

We have identified six stages in the cycle of inquiry (Figure 1) for any given indicator selected by a district from the CRIS Menu:

- Take stock and prioritize

- Identify

- Plan

- Implement strategies, policies, and interventions

- Monitor progress and adjust as needed

- Analyze results

The first two steps of the cycle occur at the beginning of each school year, For a given indicator, the district takes stock of student population patterns relative to that indicator across schools and prioritizes actions to take. A parallel process occurs at the school level, where each school takes stock of where it is with regard to that indicator – data collected, supports available, procedures in place, etc., and prioritizes actions. The school then identifies and examines its own students relative to the target indicator in order to organize information for planning, since the population of students can change each year. Schools can also create lists of students who may require additional monitoring and support.

At the district level, the third step, plan, involves determining what resources are available to each school to serve students, particularly subgroups with specific needs (e.g., AP courses for students with a GPA above 3.0), and what barriers may exist to developing and carrying out a plan for providing additional resources or guidance. The district can also set college readiness goals for each school based on their student characteristics identified in the previous step. At the school level, student data should be organized to set long-term and intermediary goals and benchmarks, and the supports, interventions, and policies needed to meet those goals should be planned.

Throughout the school year, as districts and schools implement the strategies, interventions, and policies, data should be collected so that the district and schools can monitor progress and make adjustments as needed. It is critical that the data systems are organized to provide timely and easily accessible data to schools so they can monitor progress toward goals and adjust policies, supports, and interventions. Educators should closely watch the progress of students and identify and diagnose which students need additional supports.

Finally, at the end of the school year, the district and schools analyze results and assess schools’ performance on indicators and their progress toward goals, paying close attention to the performance of subgroups. The analysis of results also lays the groundwork for plans for following year. Data inquiry is an ongoing process that allows districts and schools to use information to refine and improve their college readiness efforts across school years.

Summary

The CRIS framework is intended as a tool to help districts and schools implement the conditions, processes, and supports needed to increase the number of students who finish high school ready to be successful in college. This means intervening early and matching identified students with the supports they need – but also addressing the skills, capacities, and attitudes of adults working in all parts of the school system.

Changing cultures and the policies and practices they reinforce often requires engaging stakeholders about the imperative for setting new goals and for using data aligned with the district’s current needs, rather than historical ones. It requires a system with the willingness and resources to develop ongoing cycles of inquiry that use data about college readiness to inform policy and practice. And it requires data about individual, school, and system levels, as well as across the dimensions of college readiness: academic preparation, academic tenacity, and college knowledge.

Increasing the college readiness and success rates for currently underrepresented populations such as low-income students, students of color, immigrants, and first-generation students also challenges decades of historical inequities and systemic disadvantages. Districts must then use CRIS in tandem with efforts to foster cultures, attitudes, and beliefs that reinforce the need to provide for all what was once reserved for some. It is important to recognize that shifting cultures and long-established processes and behaviors takes time and an improvement in outcomes will not be immediate. The investment is worthwhile, though, given that college readiness indicator systems not only provide the means to measure college readiness, but also develop the long-term capacity to spur, evaluate, and adjust college readiness supports and help more and more students leave high school ready to succeed.

1. See www.corestandards.org.

2. The CRIS partners worked in three urban school districts – Dallas Independent School District, Pittsburgh Public Schools, and San Jose Unified School District – and one school support network, New Visions for Public Schools in New York City, to develop this framework. AISR also worked with the School District of Philadelphia to explore the partnerships that sustain college readiness indicator systems.

3. In a previous issue of Voices in Urban Education presenting the CRIS work Oded Gurantz and Graciela Borsato (2012) of the Gardner Center outlined an early version of the CRIS framework (see http://vue. annenberginstitute.org/issues/35/building- and-implementing). This article incorporates and refines some of the material from that earlier version.

4. For a review of the research on noncognitive factors, see Nagaoka et al. in this issue of VUE. For a concrete example of the need to go beyond academic preparation, see Jayda Batchelder and Courtnee Benford’s piece in this issue of VUE on Education Opens Doors in Dallas.

5. See Gurantz and Borsato (2012) for an early version of the CRIS menu and examples of how districts might use it. A new version, in development, is scheduled for release in 2014.

Gurantz, O., and G. N. Borsato. 2012. “Building and Implementing a College Readiness Indicator System: Lessons from the First Two Years of the CRIS Initiative,” Voices in Urban Education 35 (Fall):5–15.

Turner, S. 2004. “Going to College and Finishing College: Explaining Different Educational Outcomes.” In College Choices: The Economics of Where to Go, When to Go, and How to Pay for It, edited by C. M. Hoxby. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.