Equity-Driven Public Education: A Historic Opportunity

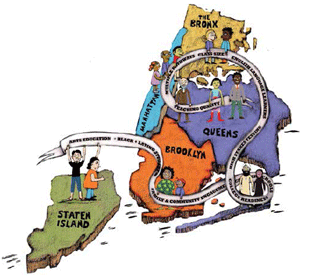

An array of community organizations forged a citywide coalition in New York City to create an equity-driven education vision and impact the 2013 mayoral campaign and election.

The vote is in.

The election of Mayor Bill de Blasio in November 2013 was a historic moment for proponents of student-centered, equity-driven public education. During the campaign, de Blasio ran on an agenda of ending New York City’s “Tale of Two Cities” and elevated a comprehensive vision for improving the city’s more than 1,800 public schools as a cornerstone of that agenda. His vision includes many of the signature reforms fought for by advocates throughout the twelve preceding years of the Bloomberg administration: the creation of 100 community schools in his first term; supports for struggling schools, rather than school closings; reduced reliance on disciplinary measures that remove students from classrooms; and an accountability system that relies on measures other than standardized tests.

Then, just prior to the resumption of classes after the schools’ break, Mayor de Blasio appointed Carmen Fariña, a long-time partner to the city’s leading parent organizations and an experienced progressive educator, who announced almost immediately that improved engagement with parents and communities would be a hallmark of her tenure. The articles in this issue of VUE describe how an array of long-standing organizations forged a new level of partnership and drew in dozens of new partners to impact the education debate throughout the mayoral election. While these organizations never collectively endorsed any candidate, their work created a climate where all viable candidates were forced to take clear positions on some of the most heated education questions facing the city. Their work also provided vibrant opportunities for thousands of previously unengaged New Yorkers in communities throughout the city to share their views about education through an innovative and in-depth community engagement effort.

The history behind the 2013 effort

A history of work in New York City on education by a trio of education organizing coalitions is what made this possible. The ten grassroots membership organizations that make up the membership of New York City Coalition for Educational Justice (CEJ) and the Urban Youth Collaborative (UYC), the city’s leading parent and student organizing coalitions, over the past decade built a track record of policy wins rooted in the real needs of parents and students in some of the city’s most politically and economically marginalized neighborhoods. Along the way, these organizations developed practices of cross-organizational collaboration that laid the groundwork for the efforts described in this issue.

They were joined over the course of 2013 by a powerful statewide advocacy partner, the Alliance for Quality Education (AQE), which had joined forces with UYC and CEJ a few years prior, in efforts to mitigate the potential silencing effects of Bloomberg’s mayoral control proposal. While the groups won some concessions in that fight, Mayor Bloomberg’s proposal passed the state legislature. In spite of this, the partnership forged by city-based coalitions CEJ and UYC with statewide partner AQE remained active through subsequent community fights on school closings and annual advocacy around the state budget. In 2013, AQE joined UYC and CEJ in pulling together broad-based coalitions of labor and community partners to mount an unprecedentedly complex and savvy campaign for the city’s public schools.

While community organizing campaigns typically involve a linear and escalating set of actions to push a desired change in policy or practice, the groups involved leading the 2013 election efforts were faced with a novel challenge: How could they win the hearts and minds of New York City residents for an approach to improving education in our K–12 system that would be a sharp departure from the policies of the Bloomberg administration?

Listen and amplify

As the articles in this issue describe, the groups took on a two-pronged strategy to address this challenge. The first advanced a key set of “wedge issues,” which were shared strategically with candidates for mayor and others. Candidates were asked to take public positions on these issues and thus to share their views on controversial issues such as testing, school improvement, closings and co-locations, and school discipline and safety.

The second pushed the trio of long-standing education organizing coalitions into a listening posture: staff and member leaders from CEJ, UYC, AQE, and their constituent organizations drew dozens of other groups and institutions into an effort to bring these key questions and others to New Yorkers across the city and engage them in creating a comprehensive vision for reform.

The result of these two strategies? An echo chamber, where the triumphant voice, once the votes were cast, was one that elevated values of equity, community, and student-driven learning.

The partners in the 2013 effort learned a tremendous amount from their work together. Youth and parents dialogued with educators and policy experts to advance a shared agenda. Frontline organizers coupled their efforts with sophisticated political strategists and developed their own capacities to use social media and other tools to get their messages out. Along the way, as is evident from the articles in this issue, a growing number of community activists developed a high level of alignment around a comprehensive vision for education reform in New York City.

The issue opens with an article by Billy Easton, executive director of AQE. He outlines the context of twelve years of the Bloomberg administration and describes the two-pronged strategy with which community organizers seized the unprecedented opportunity presented by the 2013 election. A sidebar from high school senior and youth activist Ashley Payano offers her perspective on the Bloomberg years and her involvement in UYC’s campaign.

Fiorella Guevara, a program associate at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University (AISR), offers a detailed picture of PS 2013, one of the strategies described by Billy Easton. PS 2013 – organized by a coalition that included community-based organizations, parent and youth organizers, and other groups – engaged educators, researchers, and community residents to create an education platform that reflected the priorities of neighborhood residents across New York City and that was also backed by research and vetted by a cross-sector design team that included community, policy, and research experts ranging from UYC youth leaders to executive directors of some of the most prominent education organizations in New York City.

Four members of the cross-sector design team – Phil Weinberg, deputy chancellor for teaching and learning in the New York City Department of Education and former principal of the High School of Telecommunication Arts and Technology; Kim Sweet, director of Advocates for Children of New York; Doug Israel, director of research and policy with The Center for Arts Education; and Liz Sullivan-Yuknis, Human Right to Education Program director at the National Economic and Social Rights Initiative – talk about developing policy grounded in PS 2013’s public engagement effort with Megan Hester, AISR’s principal associate for New York City organizing.

Julian Vinocur, AQE’s director of campaigns and communications, describes the key role that communications and social media played in impacting the debate on education policy in the mayoral campaign.

Pedro Noguera, professor of education at New York University and a noted researcher and national commentator on the impact of social and economic conditions on education reform, shares his perspective on the significance for education reform of the New York City mayoral election in an interview with me.

María Fernández, a long-time youth organizer, and Ocynthia Williams, a long-time parent organizer, describe the years of activism that they and their organizations built on to place a new education agenda at the center of the 2013 mayoral election.

The issue closes with an article by Zakiyah Shaakir-Ansari in which she traces her trajectory from an introverted parent in the New York City public schools, to parent leader, to the face of the community for educational justice in New York City during the 2013 mayoral election, to member of the new mayor’s transition team. In a sidebar, youth organizer Maria Bautista adds her perspective on what the campaign and the election mean for the transformation of the educational lives of the city’s students.

The efforts described in these articles brought about growth. Parent and youth leaders within CEJ and UYC managed concerns about their own autonomy, as they worked to ensure that other coalition partners would address the issues most central to their community constituencies. Experienced policy experts and educators emerged from their issue silos and areas of specialization in order to co-create an agenda that addressed the needs of a wide array of groups. Small community-based organizations and mammoth school support organizations acknowledged each others’ best intentions and critical importance to this effort and listened to one another.

For the first time in recent memory, a large swath of progressive New York City stakeholders and the city’s leadership are aligned around a common educational vision. It is one that seems to run counter to many of the nationally dominant “corporate-style” trends in school reform. However, recent events provide some wind under the aspirations of this new day in New York. U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan recently issued a powerful federal guidance to school districts encouraging them to remedy disparities in the use of exclusionary discipline (USDOE 2014). Congress’s most recent budget allows school transformation funding to be used for any evidence-based school improvement effort, no longer requiring drastic changes in staffing or school closings and opening the door to community-driven reform efforts. In communities across the country, dissent is growing regarding high-stakes consequences based on an over-reliance on standardized testing.

The organizers and advocates who have contributed to this issue are eager to both lead and follow as their city takes part in this national shift.

U.S. Department of Education. 2014. “U.S. Departments of Education and Justice Release School Discipline Guidance Package to Enhance School Climate and Improve School Discipline Policies/Practices,” U.S. Department of Education (January 8)