Meeting the Needs of Refugee and Immigrant Students and Families in a Culturally Responsive Way

Through family engagement and expanded learning time, a partnership between the district and a community organization in Lowell, Massachusetts, serves the social and academic needs of refugee youth and other English learners and their families.

“Wow!” I remember looking at the crowd in the auditorium from my spot on stage. I was excited to see over one hundred people eagerly waiting to see our Celebration of Learning – the culminating event at the Gateway Summer Enrichment Academy, a four-week program of the Lowell (Massachusetts) Public School District, where I (Barbara Roberts Hodgson) teach newcomer and ELL students. I was touched by the expressions of pride on the adults’ faces and by the sheer joy on my students’ faces.

It was a moment I will always cherish – and it was months in the making. The year before, the number of parents attending our first Celebration of Learning was very low – only about twelve parents and family members. I met with summer school personnel to debrief and discuss the successes and areas of need, and we all felt we needed to get the parents involved early and often.

As program coordinator of the summer academy, I worked all year with Dahvy Tran, the youth program coordinator at the International Institute, a community- based organization in Lowell that helps immigrants and refugees build new lives in our community, and with our Lowell Public School District (LPSD) support staff to do all we could to enable the parents to attend the Celebration of Learning. This included strengthening school-home communication and creating a student-to-student mentoring program at the International Institute.

Who were the students? What was the program? Why didn’t the parents just jump in their cars and show up? Isn’t this what parents who are really interested in their children’s education would do? Why was it so difficult to foster parental involvement? If any of those questions seem unimportant to you, then stop reading right here, because it is the answers to those questions that make education – all education, working with any youth, not just young refugees and immigrants – meaningful, respectful, and genuine.

Why were these questions so important to us? After all, we fulfilled all of the requirements of the grant that funded our summer academy;1 shouldn’t we have just been happy it was the last day of our summer program? Actually, we were all sad that it was the last day. As the students got on their buses, a boy started to sing “Stand By Me,” one of the songs the kids learned for their concert. One by one, the students started singing with him. Many of the teachers and students were crying. Why was this such a powerful moment? The students, like any youth, wanted to feel like they were part of something. The summer program gave them that. The feeling of community and connectedness was incredible.

The success of our Celebration of Learning underscored the success of our district-community partnership, which allowed us to serve the diverse needs of these students and their families beyond the summer academy itself. In addition to the academic and social support we provided to students over the summer, we made a concerted effort to reach out to parents to build trusting relationships and provide logistical help and training. We were able to continue our work with these families during the school year by developing an after-school program for refugee students.

LOWELL’S IMMIGRANT AND REFUGEE STUDENTS

Lowell, Massachusetts, is a diverse urban center with a fascinating history. It was designed and built in the late 1800s to serve the water-powered mills along the Merrimack River – and grew quickly during the same period. Immigrants have always been part of Lowell’s character, and the refugees who are arriving daily have some experiences in common with those who came before them. But today’s refugees are arriving with an unprecedented number of factors working against them. Traditionally, immigrants settled in Lowell for economic opportunity. Many fled poverty or war-torn countries, but the overall immigrant experience was very different from the experiences confronting today’s newest arrivals to Lowell.

The difference between immigrants and refugees is that immigrants voluntarily move to another country – sometimes due to political and economic reasons – but refugees are sent by the United Nations. Countries all around the world volunteer to accept refugees, and then individual cities agree to accept a specific number of refugee families. Sometimes, if a refugee has close family ties with a previously resettled relative, it might be possible to settle in the same location.

I once had an irate parent – a White, middle-class mother – say to me,

Why can’t my kid go to your summer program? It’s not fair that all these people who come to Lowell get all the fun programs for their kids. They choose to come here, they should have the same treatment my kid gets.

If more parents like this one understood the realities faced by immigrant and refugee youth, perhaps they would not be asking this question and would instead welcome and support their new community members.

Anxiety and Resilience: What It’s Like to Be a Refugee Student / Dahvy Tran

As a former refugee youth, I understand the challenges that many of the newcomers face in making Lowell their new home. My family came with the wave of Cambodian refugees in the 1980s. I was fortunate to be young enough to complete my education through the school system here. My older siblings were less fortunate, in particular my eldest brother, who was enrolled in eighth grade upon our arrival halfway through the school year.

It was a struggle for him to keep up with the coursework while trying to learn the language, yet I could never recall him being frustrated or angry. He assumed the role of parent while my mother worked several jobs to support us; he acted as interpreter when she faced difficulty in communicating with others. When he was old enough to work, his wages helped relieve some of the burden from my mother. Resiliency and integrity are the words that come to mind when I think of my brother. Now, working with the newcomer students, I see the same resiliency and integrity in everything they tackle.

Newcomer refugee students need all that resilience and integrity just to get through every school day. Imagine your very first day of a new high school. New classrooms, new faces, new everything. You walk down the hall and the bell rings for your first class. You, along with everyone else, rush around looking for the correct classroom number. Then you scurry in and take a seat without making eye contact with anyone. As the teacher begins speaking you heave a big sigh of relief knowing that the worst is over. Now imagine learning all this in another language. All of the students I work with have similar stories, but for them there is no sigh of relief at the end, instead only mounting anxiety. It takes a few months for these newcomer students from Somalia, Congo, Burma, Iraq, and Nepal to be able to adjust to the school setting.

ABOUT THE SUMMER ACADEMY

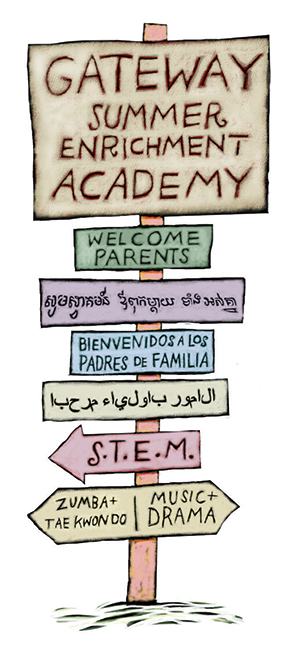

The Summer Academy was held at the Stoklosa Middle School in Lowell. The program had an academic component and an enrichment component. All students participated in the core academic classes, and all students participated in two or more of the enrichment options. We partnered with the Tsongas Industrial History Center staff, who provided STEM-based science activities;2 we offered Taekwondo and Zumba classes; and we had a music and drama program. We partnered with the International Institute of Lowell to help with outreach.

The participants in the Gateway Summer Enrichment Academy were all English language learners (ELLs). According to statistics from the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education for 2014-2015, 36.3 percent of Lowell’s students have a first language that is not English, compared to 18.5 percent for the state; 26.6 percent of Lowell’s students are classified as English language learners, compared to 8.5 percent for the state. Within this English language learner category, there are several subgroups – the majority of the summer program’s participants were classified as “newcomers” or as “students with limited or interrupted formal education” (SLIFE). We had 125 students in grades 5 through 12 from countries in Africa, Central and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Central and South America, and the Caribbean.

Many of the summer program students worked with Dahvy on Fridays. Our program was Monday to Thursday, so the Fridays at the International Institute were an unofficial extension of the Gateway Summer Enrichment Academy program.

Friday Sessions and Youth Fellows: Community-District Partnerships to Support Newcomer Students / Dahvy Tran

Fridays at the International Institute of Lowell provided additional academic support for students who needed more help with English reading comprehension, among other needs, and also included social activities and leadership development. One Friday of each month, we would hold a Friday Fun Day, where the students got to vote on an activity they would like to do together that was not academically focused. Thus far, we have had Taboo board game competitions, movie afternoons, soccer games, and food celebrations.

We established a Youth Fellowship program during the school year prior to the Gateway Summer Academy for two reasons. First, there was a language barrier; many of the new students arriving could not communicate with the English-speaking tutors we recruited. The Youth Fellows (as we refer to the leaders from the Youth Fellowship) have the language capacity to interpret for the new students, are high achieving in their academics, and have been trained with basic tutoring skills.

Secondly, the Youth Fellows were already natural leaders in their communities by interpreting for new families and helping them navigate the city. The Fellowship program also assisted the students further with things they were struggling with, such as college preparation; offered one-on-one support; and gave guidance on life, relationships, and school. Although not formally written in my job description, I act as both mentor and case manager for the youth. The investment that I place in the Fellows would be magnified ten-fold if they each help between ten and fifteen new youth. Even though I was the only staff for the youth department, through our twelve Youth Fellows, I could reach out to about 150 to 190 youth. (In total we have eighteen Fellows, but six are currently in college and return during the summer to assist.)

What is unique about my work is the strong collaboration I have with the public school system, as well as with our other community partners in the city. I come to the high school at least one day a week and have daily communication with Barbara Roberts Hodgson. I have the support of the school’s administration and community partners to continually develop the youth programming to meet the needs of the families we serve. In Lowell, there is a Newcomer program for refugee youth through the schools. I work closely with administration and ELL teachers to connect classroom learning to our after-school program. I spend as much time in the school as I do after school. My consistent presence builds trust among the youth, teachers, and parents.

Building Trusting Relationships

The Celebration of Learning, on the last day of the Gateway Enrichment Academies program, was an exhibition of students’ academic work and included a Taekwondo exhibition, a play, and a concert. How did we use community partnerships to make our Celebration – and our entire summer academy – a success?

First of all, we held a parent and community meeting early in May to present the program, and then Dahvy and four of our program tutors began spreading the word about the program to the different parent groups in the community. We worked with several parents so they could go back to their communities and explain to other parents what we would be doing in the summer program, and why it was important for their child to attend. The tutors contacted many parents. Although this was a completely voluntary activity, several of them spent many hours meeting with parents, calling them, and helping to educate parents about this great opportunity for their children.

One parent in particular who attended that very first meeting and was there at the Celebration of Learning really stood out for us. This parent has a child with a visual impairment, and he was not sure he wanted his son to attend, but he came to the introductory meeting at the urging of Dahvy, who had been working with the student’s older siblings in the International Institute’s mentoring program. Dahvy was sure the student would have a positive experience.

I have the chills again right now as I remember this student’s Taekwondo performance – he had practiced, practiced, and practiced. In front of his father and mother, he ran a measured number of steps across the stage to the instructor, jumped, kicked, and broke a board. When I tell you that this was an amazing moment for the student, his classmates, his teachers, and family, I want you to remember that this father wasn’t sure his son should attend the program, and it was because of Dahvy’s and the tutor’s efforts that this student earned a standing ovation. He couldn’t see the audience standing, but he could hear and feel the applause.

I had him in class this year at the high school, and every once in a while, he would ask me if I remembered the time he broke the board in front of his father. He says it was the best moment of his life. This is an amazing example of the power of communication and community partnerships. If we had simply handed out registration forms, this student would never have attended the program. But because Dahvy had already developed a trusting, respectful relationship with his siblings through the Institute’s after-school program, he had the opportunity to attend the summer program.

These trusting, respectful relationships are absolutely crucial to any kind of meaningful interaction with parents, but there are several obstacles and challenges that make it very difficult to even begin to cultivate such relationships. Refugee parents are subject to many stresses, and the family dynamics are often extremely different once a family resettles in Lowell. Parents from all ethnicities, religions, and socio-economic and educational backgrounds suffer from common fears, doubts, and suspicions. Many parents fear that they are going to lose, or have already lost, their authority as head of the family.

Keeping in Touch

How do we help families with the difficult adjustment period they go through in the first months after their arrival? Dahvy and I have been calling families for the two years we have been working together. We call to tell the parents about important events, and sometimes just daily occurrences. We call to explain LPSD website information, we call to tell them about their child’s progress. The theme here is: WE CALL. In the summer program, our student interns, part-time liaison, teachers, and tutors all had ten to fifteen minutes built into the staggered schedule to call parents. Each parent received a minimum of four calls during the four-week program. We called to say thank you for sending their child, we called to tell them about special moments, we called to tell them how great a student did on the Tsongas Egg Toss. We called, and called, and called. Even if we weren’t sure the parent understood everything we said, we called so that every parent had friendly calls about their children.

This calling system worked extremely well. Two weeks into the program, we had a parent focus group meeting in the middle of the day at the International Institute. We provided tea, coffee, some sweets, and interpreters. We had so many parents show up that we had to move into a larger space. The year before, we had only had four parents. I attribute the large turnout to the telephone calls and the outreach efforts of Dahvy, the interns, the part-time liaison, teachers, and tutors.

It turned out that the parents had a lot to say, and we wished we could have stayed and talked for another hour. Several parents talked about how pleased they were that their children were still in school during the summer. A couple of parents liked the fitness component of the program, especially since they thought the physical education classes their students participated in the school year were, “boring, crowded, and had no equipment.” Many parents were concerned about what the children would do once the program ended, and several parents wanted an extension of the summer program. It was a very positive, eye-opening experience for all of us.

Another way we connected with parents is that we gave out Celebration of Learning flyers to all of the students three times. Dahvy had a stack at the International Institute. Our student interns, teachers, and tutors took extras home so if they happened to see a parent of a summer school student in any situation, they would give out another invitation. This was very successful; the auditorium was full!

Help with Transportation

The parents of our students can’t just jump in a car and go to the summer school site. We realized that we needed to pass out bus tokens, explain directions, and make sure everyone could attend. The support we received from LPSD staff was great. We handed out about one hundred bus tokens, and we ended up with more than one hundred parents and family members at the celebration.

HELPING FAMILIES NAVIGATE LIFE IN AMERICA

In many cases, interpreters, or even the children themselves, have the task of navigating the convoluted demands of school registrations, MassHealth applications, and other forms of bureaucratic paperwork. Losing the power of being able to take care of everything can be depressing and make parents feel disoriented as they try to find their way in America. Can you imagine trying to reconcile your familiar expectations of education, culture, and family life in your home country with the realities of life in America?

Parent Training Sessions and Communication Building

Dahvy and I work together to help teach the parents how to access the district’s Aspen Family Portal3 so that parents can see their student’s attendance, grades, and important documents. Most of the information is in English, but tools in Google Docs are making translations easier. We at least feel we are giving some authority back to parents by showing them how to access this portal. We held parent trainings at Lowell High School and at the International Institute.

During one session in February, a mother came in with a friend who explained that the mother wanted to know when the daughter would be getting a report card. I showed the mother the girl’s grades, attendance, assessments such as MCAS and ACCESS, and conduct reports.

The young lady in question was soon participating in the after-school tutoring program at the International Institute, but not before she complained that we showed her mom how to check up on her. This proved to us that our parent training sessions were working!

It also shows that teenagers are teenagers, regardless of where they are from, and that ALL parents want to know how their students are doing. We have to work together to make sure the parents understand the school’s and the community’s expectations for the student and the family. In many cultures, parental involvement in schooling is an unknown element; parents often feel that the teachers know best, and they have complete trust in the teachers and schools. It is important not to judge this as “detachment” and think a parent isn’t interested. If we can strengthen any school-home communication link, we can potentially help a student succeed.

KEEPING THE SUPPORT AND RELATIONSHIPS GOING: THE AFTER-SCHOOL PROGRAM

When school started up again a few weeks after the summer academy ended, Dahvy and I worked on several ideas as to how we could continue to foster the relationships we forged in the summer to continue to help our refugee families navigate the school system and find the help and support necessary to ensure that each refugee student in the LPSD had a plan for success. One idea was the after-school program.

Creating a Safe and Consistent Space / Dahvy Tran

The after-school program focuses on creating a safe and consistent space for refugee youth from all backgrounds to interact and develop their English language skills. The main goal of the after-school program is to help youth with their homework, but it also serves as a bridge to widen their social networks and help them feel that Lowell, and the International Institute, is now their home. Refugee and immigrant youth have taken advantage of our after-school program. My personal experience and research on best practices4 have shaped the development of the youth programming. The East African Community Services (EACS) After-School Program and the Involving Refugee Parents in the Manchester Public Schools program greatly influenced our youth programming in the beginning. The EACS After-School Program’s objective is to “provide a safe, consistent space for the students to get basic homework assistance while honoring and preserving their diverse cultural heritage,”5 while the Manchester School district’s program objective is to “help refugee families integrate into the school and the larger community in a manner that includes food, fellowship, and fun. In addition, teachers, administrators, and other community members are provided with opportunities to get to know the newest families in town.”6 I started my work with the goal of integrating both models and piloting the result here in Lowell. Since the program’s inception, we now have eighteen graduates from our Youth Fellowship Program – the leadership track for refugee and immigrant youth who serve as tutors during the homework help after-school sessions and ambassadors to the community at large. We have also served 146 youth and parents, who are now comfortable in navigating the school system on their own but who know we are still a part of their support network. One parent that comes to mind has a physically disabled son and was fearful that his son would be neglected in the classroom; their previous host country had placed the son in an empty room all day until the parent came to get him. The process to enroll the student and have him in the appropriate classroom took longer, but through it the parent met several school staff and administrators who showed him what supports were available for his son. Now that same parent is showing new parents around the school system he once feared.

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO DO THIS WORK?

Districts and schools can learn a lot from our successes. Some of what we were able to achieve has a low cost. With the help of volunteer staff time, it does not cost anything to make a phone call, it costs very little to feed a group of kids after school, and resulting connections made with parents and youth are priceless.

But sustaining great programming is hard when school districts constantly scramble for money. This is unfortunate, because I believe quality summer programming should simply be part of a school year budget. SLIFE students have tremendous gaps in education, and summer programs are crucial for them if we expect them to learn English and content at a proficient enough level to pass all of the state-mandated testing required for them to earn a high school diploma.

Changes to the Gateway Cities funding in an effort to balance the state budget resulted in districts not getting funded for the third year of the program, which would have been this year. In Lowell, this meant that the district funded a drastically reduced refugee summer program that served 40 refugee students from fifth through twelfth grades in the summer of 2015. We saw the impact our program had on more than 100 students in 2013 and 2014. We hope that the inclusion of this program in the yearly state budget in the future will allow us to continue to serve this population of students in the way they need and deserve. It would be shortsighted to spend less today on helping these students become more self-sufficient and successful, when the goal of this program was to strengthen and increase the capacity of Gateway Cities across the Commonwealth.

The Unseen Cost / Dahvy Tran

The work that Barbara and I do together is an example of a successful model, but it comes at a cost that’s usually unseen. The other side of the work we do does not happen during work hours. I spend countless weekends and evenings working with both students and parents to help them overcome barriers to understanding and educate them on navigating not only the school but the community at large. My own refugee background with my family gives me the unique perspective to understand that parents want to be part of their children’s lives, but their multiple jobs and responsibilities keep them outside of this realm and force them to rely on their children as the source for all this information. Every new parent I meet for the first time, every home visit I make, and every event I bring parents to, I tell them they are the best decision makers for their children’s future, and that I’m only the messenger. Districts, schools, and organizations such as the International Institute are always looking for more funding so that we can have more messengers to act as the bridge for the parents and students.

For more information visit the International Institute of Lowell.

1. Through the Massachusetts Educational Opportunity Office’s Gateway Cities Education Agenda, $3 million in grants were awarded in 2013 and 2014 to address the English language development of immigrant and newcomer students in the Gateway Cities Summer English Language Enrichment Academies, held across twenty districts in Massachusetts.

2. The Tsongas Industrial History Center is a partnership between the University of Massachusetts Lowell Graduate School of Education and Lowell Natural Historical Park. See http://www.uml.edu/tsongas.

3. For more information about the portal, see http://www.edline.net/pages/Lowell_High/Parents___Students/Aspen_Portal/....

4. See, for example, Weine 2008.

5. See http://www.brycs.org/promisingpractices/promising-practices-program.cfm?....

6. See http://www.brycs.org/promisingpractices/promising-practices-program.cfm?....

Weine, S. 2008. “Family Roles in Refugee Youth Resettlement from a Prevention Perspective,” Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 17, no. 3 (July):515–532. Available online at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1056499308000205