Why Families Are Engaged in Early Learning in Central Falls, Rhode Island

We Are A Village, a program funded by a federal Investing in Innovation grant focused on family engagement in early childhood, fosters parent collaboration during early learning transitions to help families feel welcome, valued, and respected.

"How do we get parents to show up?” As a researcher who studies family engagement, I [Joanna Geller] hear this question all the time – in school faculty meetings, at family engagement conferences, in working groups with nonprofit leaders. It always unsettles me a bit, because the question is invariably referring to parents in schools where the overwhelming majority of students are of color, and the answers that typically follow tend to focus on changing the parents rather than the school, program, or event that parents are expected to take time away from their families or jobs to attend. Over the past two and half years of evaluating We Are A Village, a highly competitive federal  Investing in Innovation (i3) grant focused on family engagement in early childhood in Central Falls, Rhode Island, our research team at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University (AISR) has gained much insight into the transformational process that occurs when a school system and community partners ask, “What can we do to help families feel welcome, valued, and respected?” rather than, “How do we get parents to show up?”

Investing in Innovation (i3) grant focused on family engagement in early childhood in Central Falls, Rhode Island, our research team at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University (AISR) has gained much insight into the transformational process that occurs when a school system and community partners ask, “What can we do to help families feel welcome, valued, and respected?” rather than, “How do we get parents to show up?”

Early learning transitions are a particularly important time for educators to consider this question, not only because family engagement during this time is associated with improved student academic and socio-emotional outcomes (Crosnoe & Cooper 2010; Iruka et al. 2014; Powell et al. 2012),1 but also because transitions can produce great anxiety and feelings of isolation for children and their families (Berlin, Dunning & Dodge 2011; Kreider 2002). As Anne Henderson (2015), a longtime leader in the field of family engagement, writes, “Let us remember that it is not just the children who enroll in school, it is the whole family.” Often, the kindergarten or elementary school to which a student transitions has different cultures and routines than the child’s previous school and is less culturally responsive than the preschool setting (Miller 2015). For some parents, bringing their child to a new kindergarten is the first time they themselves have been inside a school since their own school experience, which might evoke painful memories. Furthermore, immigrant families may be experiencing the U.S. public school system for the first time. Families of children with special needs must learn what services are available for their students, and families of children whose native language is not English may need to understand the different types of instruction the school offers English language learners. On top of all of this, most parents worry how their children will fare academically and socially in a new setting. Therefore, schools have a special responsibility during early learning transitions to help families feel welcome, valued, and respected.

THE CENTRAL FALLS i3 WE ARE A VILLAGE INITIATIVE

Central Falls is a one-square-mile city in northeastern Rhode Island, with a population of 19,000. The Central Falls School District (CFSD) is 74 percent Latino, 12 percent Black, 9 percent White, and 4 percent multiracial; 79 percent of students are eligible for free or reduced price lunch; and 24 percent of students are English language learners. In 2013, CFSD, in collaboration with Children’s Friend of Rhode Island and the Bradley Children’s Research Center, was awarded a $3 million i3 grant with the goal of expanding and enriching opportunities for family engagement in early childhood. The goal was for every family to feel welcome, valued, and respected in their children’s schools and for schools to connect families with one another and with community resources. Children in CFSD are in the unique position of changing schools three times in their first three years: when they start pre-K, when they move to a new building for kindergarten, and again when they move to yet another building for elementary school.

Supporting students and families with these transitions was a key goal of the grant. To this end, the grant allowed the district to hire a full-time bilingual “parent collaborator” for each of the five schools; create a parent room in each school; and provide regular parent coffee hours, opportunities for parents to receive training and mentoring to become leaders in the schools, parent workshops, and an evidence-based parenting training called Incredible Years. We Are A Village was inspired by the Head Start Family and Community Engagement Framework, which asserts that family engagement extends far “beyond the bake sale”; it also entails parents being physically and emotionally healthy, lifelong learners, and advocates and leaders. The framework focuses on how this engagement happens, not solely on what it involves. The goal is not just to get parents to show up at coffee hours or to visit parent rooms, but to truly engage them through relationships that are rooted in trust, respect, and reciprocity. These relationships ensure that when families make sacrifices to show up at their children’s schools, the experience is meaningful for them and for their children.

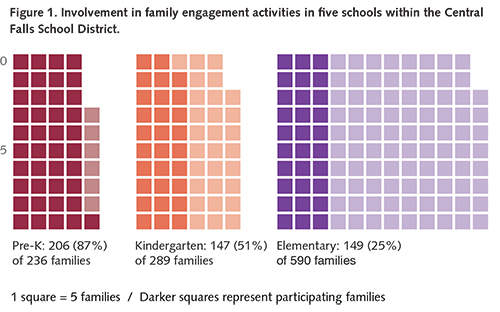

Our evaluation data speaks to the great success of the i3 initiative in helping families to feel welcome, valued, and respected in their children’s schools. As shown in Figure 1, 87 percent of preschool students, 51 percent of kindergarten students, and 25 percent of elementary school students in the participating i3 schools had a family member who engaged in at least one i3 family engagement activity, such as attending a workshop, volunteering, or having a one-on-one meeting with a parent collaborator. Data from the focus groups we conducted with 100 family members illuminate how families felt when they came to the schools. One parent said:

You know when you feel welcome in a place and you know when you don’t feel welcome. They make it feel welcome. We always have bagels and coffee. Parents know each other already in coffee hour, so they feel comfortable. Valued? You feel valued because they ask a lot of questions. They hear your opinions. They don’t just talk, talk, talk, talk, talk. They ask questions, and they hear your opinions, whatever you have to say... They never disrespect.

Although we cannot determine from our evaluation that increased family engagement caused better outcomes, evidence suggests that it is paying off for improving student outcomes. For example, among students who had been chronically absent (missing more than 10 percent of the school year) during 2013-2014, when families engaged in at least one i3 activity, their child’s risk of being chronically absent again the following school year was reduced by 32 percent.

ROOTS, RELATIONSHIPS, AND RESOURCES

So, what’s the secret in Central Falls? Why did so many families engage with the schools? To answer this question, I turn to a framework from the field of community organizing. Groups that mobilize and organize communities in an effective and authentic way have 3 Rs: roots, relationships, and resources (McAlister & Catone 2014):

-

Roots involve a sustained commitment to serve and develop a particular neighborhood, staff with shared histories and identities with residents of that neighborhood, and values of equity and justice.

- Relationships involve collaboration with parents and residents – the constituencies critical to community-based school improvement efforts – as well as the ability to connect community members with one another and with educators and system decision makers.

- Resources include trained staff and an administrative infrastructure, which are necessary for the labor-intensive and skilled work of community outreach.

Individuals and organizations with roots, relationships, and resources are often called “cultural brokers.” Cultural brokers help culturally and linguistically diverse families navigate the language, customs, and norms of the school and school system while simultaneously affirming parents’ own culture and rights. In the sections that follow, Maria Cristina Betancur, one of the i3 parent collaborators, describes how her roots in the Central Falls community, her relationships with families, and the resources she and her colleagues share have changed how families engage with their children’s schools.

PARENTS AS COLLABORATORS IN THE CENTRAL FALLS “VILLAGE” / MARIA CRISTINA BETANCUR

As a parent engaged in my children’s education, I can testify how important family engagement is. I’m a proud parent of two successful children (now adults) from the city of Central Falls. On a basic level, family engagement meant learning together, as my children and I became colleagues in learning how to support each other. Their contribution was to put forth their best effort to complete assignments, and my contribution was to find support to assist them when I wasn’t able to help them myself. On another level, family engagement was about building strong two-way communication with teachers to make sure that the teachers, my children, and I understood the gradelevel standards, so they could receive support on time or have an opportunity to have advanced classes. Finally, as a parent leader and an i3 parent collaborator, I had the opportunity to share my knowledge with other parents, to offer time to the school to contribute, and to transfer the knowledge from school to home and vice versa. These levels of engagement taught me that we grow only when we recognize the participation of others in our lives.

Roots

I feel privileged to live and work in the same community. I’m an immigrant from Colombia, South America. I came to live in Central Falls in 1993. My language barriers and my disconnect from my culture made me very vulnerable. My husband and I made a commitment with each other to build a family in a circle of love so we could strengthen one another. We understood how painful it could be to be disenfranchised from the community in which we were living by not knowing the language, the culture, and the people around us. We brought our children into this circle of love. We worked two jobs for many years and we paid a lot of money to babysitters, but we built an unbreakable family. While I worked for years doing cleaning and at factories, I always managed to make time to support my children’s school, even requesting time off to volunteer as a chaperone at events, school activities, Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) meetings, and to attend parent/teacher conferences.

Gradually, I became part of the community of Central Falls, although everything in my life was obtained with much sacrifice. After my labor rights had been abused, I co-founded a local non-profit organization focused on labor rights, Fuerza Laboral/Power of Workers. But I never had any problem with my children’s education or with the school system until 2009, when my son was in ninth grade and Central Falls High School received national media attention due to persistent low performance. I wasn’t prepared for something like that. There’s nothing scarier than to hear that the only high school in your city was among the “worst” in the country. The news was saying bad things about the school every single day, but I’m the kind of person who likes to learn about things for myself, and I wanted to get more involved. I went to my place of work with some newspapers to explain to my supervisor why I wanted to request time off every Thursday, so that I could volunteer at the afterschool program at my son’s school. As I mentioned before, my son is part of my unbreakable family and I’ve always believed that education is the most important tool to become successful in life. My supervisor showed his admiration for my commitment to the education of my children, granting me permission to take time off from my scheduled work hours so that I could be a volunteer at my son’s school. (My son also become a tutor to other students of the program.)

While I was volunteering, I started listening to students and other families complain about how they felt disrespected and unwelcomed at the school. I started developing strong relationships with some teachers, administrators, home school liaisons, and families who liked the idea of having more parents volunteer at the school. The school was in need of support with many tasks such as making phone calls to students who were late or absent, providing late slips to students in the morning, supporting events, checking the hallways and classrooms, and forming a PTO. As a parent volunteer, I also represented other parents as part of the negotiations between the school district and the teachers union.

That is how my journey began as a volunteer, and I later left my factory job to volunteer at the school every single day to greet the students in the morning. Why? Many people asked that question, including family members, teachers, administrators, and even the local news. The answer was that I wanted to be the mother that I am today: the mother of two successful children who both graduated from high school as National Honor Society recipients and both continued pursuing their higher education.

With my engagement in my children’s school parent committee, I learned how to become knowledgeable about and celebrate my children’s progress, but what’s more, I learned how to develop my children’s passion for education. I always liked to read with my children, but through my engagement I developed the habits to read with them and listen to them read.

I also learned how to advocate for a better education, not only for my children, but for all children. I learned about my rights as a parent to visit my children’s classrooms. I learned about the power that parents have and how to use that power to be at the same level as the teachers. I started sharing my story with other families. Many families felt connected with it and started sharing their stories, too, and volunteering at the school. We formed a school PTO where we all exchanged knowledge and our passion for the progress of our children. We called that personal connection “peer navigation.” From parent to parent we developed the link of good communication and being a stronger community that wants to raise children with skills to compete in today’s society.

Eventually, I was hired by the school district and then as an i3 Collaborator. I started as a parent who was only interested in obtaining support for my children, but I ended up taking trainings, English classes, completing a bachelor’s degree and even a master’s degree. My life changed, and today my interest is educating other families about opportunities for their children and for themselves. I want the families to know that I understand where they come from when they struggle with their children’s education.

Relationships

What culturally and linguistically diverse parents require is not a reorientation of values or parenting classes to compensate for deficiencies, but rather partnerships with educators to foster understanding and help bridge differences. It doesn’t matter where you come from or the language you speak. When a good relationship is developed between parents and teachers, everyone wins. Teachers learn about other cultures and how to approach the students to have a better result in the classroom. Families learn to nurture proud bilingual children who can improve academically by reading in their own language. Encouraging parent involvement to heighten student achievement is also a way to share power between families, students, teachers, school staff, and the community. Part of my job as an i3 collaborator is to help parents and teachers form these kinds of relationships.

Working as an i3 collaborator, I have had many opportunities to share my experience with families and talk about how they can become more active in their children’s education. During the first year of the i3 grant, I worked at a pre-K center and I’m now working at an elementary school, so I have supported families through different types of transitions. Many families like to bring their children to school in the morning, and the best thing I can do for them is receive them with a big smile. I always start the conversation by thanking the parent for being there every day and on time. The families are more open to start a conversation when they feel appreciated and welcomed at their children’s school. I learned through experience about how to make people feel welcomed at school; the most important thing is to be a good listener. The families let you know about their personal lives not only because they want to complain or they want your help, but because they need to trust someone. The families have the power; they are the ones who can change systems and structures.

I always provide families with the tools to enhance their leadership, but I also ask them how I can be useful to them instead of assuming that I know how to help them. The families are knowledgeable and are a great resource; there is no one better to let us know about the progress of their children. My success with the families is the result of good communication built on respect, trust, and a genuine relationship.

A common barrier to participation for some families is the perception that they should defer to the teacher in all academic matters. Other families have the feeling because of previous school experiences that classrooms are simply “off limits” to visits or observations. Family members who struggled themselves as students may view their child’s school as a place where they are unlikely to fit in or feel welcome. Schools can remove these “invisible barriers” between families and the school by welcoming families while respecting their attitudes and beliefs. During the past summer, I was part of a team formed by home school liaisons, i3 collaborators, parent volunteers, and administrators; we made home visits to parents whose children were transitioning from pre-K to kindergarten, and from kindergarten to first grade. We made sure that all the families received information about the school (such as changes and policies about attendance, discipline, and uniforms), and made them aware of services available to students and their families. In order to become prepared for the home visit, we all received intensive training. We planned ahead about how to accomplish the goal and how to build a relationship with the families. This work was very important to the families, and to us. The families trust their most valuable possession – their children – in our hands. A home visit demonstrates that each family is an integral part of the school community and shows that the school is willing to put in the extra effort to include every family in its child’s education.

Resources

All of my personal experience as a parent and my continuing education makes me a resource for families. I became passionate about helping other parents understand the school system because I always wished to have a better understanding when my children were younger. One way I offer my resources is teaching parents about their rights. For example, many families think that they need to wait until the parent/teacher conference to meet their child’s teacher, but I always suggest families take all the opportunities the school offers to approach the teacher before the parent/teacher conference so they can meet one another in a different setting than the classroom.

I also love to help families enhance their communication with schools. When families are able to access information and advocate for their child/family, they are showing an important form of leadership. I instruct families to ask themselves: What are the means of communication between home and school? Who can I communicate with? What means of communication do we already know/use and how well do they work? Where do we go for information about our child’s education? I support families with information about the different communications systems the schools use, such as the school portal, emails, texts, and/or notebooks. Our community is very diverse, which is why many families find it difficult to communicate with the educators of their children. My own experience taught me that it is important to ask the right questions in order to receive the right answers. Although the process may seem simple, it can be a challenge for families who have language and cultural barriers or when they have to work countless hours during the day. It is important to consider how difficult the process can be and why, so I also support families through role-playing, helping them prepare for a parent/teacher conference or a meeting with an administrator or guidance counselor.

Not only am I a resource for families, but by developing their leadership skills, families become resources for one another. Although this is a community in which families work countless hours, I always count my blessings of having parents volunteering at the school. The parent volunteers support the school inside and out by sharing information with other families who cannot visit the school as often as they do.

I have found that other resources help families become engaged in their children’s schools. These include:

- Leadership training to equip parents with the tools to advocate for their children

- Workshops to learn about how the education system works and available resources

- Courses in GED, English, and computer literacy

- Referrals to services that assist with social and economic needs

- Appreciation of diversity by employing school staff from different nationalities

- Training for school staff on strategies for developing strong, trusting relationships and effective communication strategies with families

- Community celebrations and cultural festivals held at the school so that the school can center on community life

- Translation of school information into languages that parents speak at home

- Scheduling of meetings at times that are convenient for parents’ work schedules

- Homework help for students and support for families when they don’t know how to assist them (for example, in Central Falls, there are monthly workshops in which parents and teachers exchange tips to engage children in reading or math exercises)

CULTURAL BROKERS AND FAMILY ENGAGEMENT IN EARLY EDUCATION TRANSITIONS

Family engagement is particularly important during early learning transitions, as families are expected to learn about new resources and supports for their children, establish communication with teachers, support learning at home, and help their children develop positive attitudes toward school. Support from family members is a constant during the transitions from preschool to kindergarten to first grade, when children experience new schools with different teachers, classmates, routines, and expectations. Maria Cristina’s story illustrates how families benefit from relationships with cultural brokers who share common experiences, have a durable investment in the community, listen to their concerns, welcome their contributions, help them navigate the educational system, and connect them with resources. In turn, the schools and school system benefit from families who have the power and knowledge to stand up for every child’s right to a quality education.

As we have found, this process is not without its challenges. Cultural brokers are most effective when they collaborate with teachers, principals, and other staff and are considered as valued members of the school community. However, i3 parent collaborators have had to work hard to communicate their role and prove their value to school staff. They have had to figure out how to establish trust while simultaneously encouraging staff toward more inclusive and welcoming family engagement practices. Although the payoffs are tremendous, the work is hard. Cultural brokers need consistent support from one another and from school, district, and community leaders and supervisors. This process is at odds with many funders’ expectations for quick results. Cultural brokers might not yield overnight improvements in test scores, but with the right supports, they can have a long-lasting, sustainable impact on changing the culture of schools and school systems.

Unlike many family engagement efforts that focus on “fixing” families, cultural brokers in Central Falls come to families as allies. The aboriginal artist and activist Lilla Watson embodies Central Falls’ successful philosophy toward family engagement in her famous quote:

If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.

1 Most research has linked home-based family engagement to student outcomes in early childhood, particularly “literacy-rich” activities, such as reading, telling stories, singing, and visiting the library. However, there is also evidence that school-based interventions that are culturally responsive and meaningful to families can improve student outcomes.

Berlin, L. J., R. D. Dunning, and K. A. Dodge. 2011. “Enhancing the Transition to Kindergarten: A Randomized Trial to Test the Efficacy of the ‘Stars’ Summer Kindergarten Orientation Program,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 26, no. 2:247–254.

Crosnoe, R., and C. E. Cooper. 2010. “Economically Disadvantaged Children’s Transitions into Elementary School: Linking Family Processes, School Contexts, and Educational Policy,” American Educational Research Journal 47, no. 2:258–291.

Henderson, Anne. 2015. “The Night Before School Starts . . .” National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement, 15 September.

Iruka, I. U., N. Gardner-Neblett, J. S. Matthews, and D. C. Winn. 2014. “Preschool to Kindergarten Transition Patterns for African-American Boys,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29:106–117.

Kreider, H. 2002. Getting Parents ‘Ready’ for Kindergarten: The Role of Early Childhood Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Family Research Project.

McAlister, S., and K. Catone. 2014. “Neo-Wave Organizing: Different Side of the Same Coin or a Whole New Currency?” Paper presented at the International Network of Scholars (INET) 17th International Roundtable on School, Family, and Community Partnerships, Philadelphia, PA.

Miller, K. 2015. “The Transition to Kindergarten: How Families from Lower-income Backgrounds Experienced the First Year,” Early Childhood Educational Journal 43:213–221.

Powell, D. R., S. Son, N. File, and J. M. Froiland. 2012. “Changes in Parent Involvement Across the Transition from Public School Prekindergarten to First Grade and Children’s Academic Outcomes,” The Elementary School Journal 113, no. 2:276–300.