Case Study: The New York Performance Standards Consortium

The story of the Institute for Health Professions at Cambria Heights illustrates the positive impact of using performance assessments rather than relying on the state Regents exams.

MY PATH AWAY FROM THE TEST (GARETH ROBINSON)

I was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies. When I was three, my mother, brother, and I immigrated to the United States, joining my grandmother and two uncles in a one-bedroom apartment in Martin Luther King Towers, a public housing development in northwest Washington, D.C. My grandmother and mother worked for a wealthy family whose children attended an independent school, and soon my mother became determined that her sons, too, should attend an independent school.

Ultimately, my older brother was accepted at Sidwell Friends, a Quaker school now known as the school favored by the children of the Washington elite; I joined him when I entered fifth grade. Before that, I had attended a parochial school and then Adelphi Elementary, a public school in Prince George’s County where my mom moved us to pursue a better life. Although I had been accepted to the gifted and talented program at Adelphi, my mother had not given up on her dream of an independent school for me. I remember missing school so I could be tested and visit different independent schools.

I was excited to start Sidwell, because I had seen during my visit that the school had so many things that Adelphi did not. Beyond the physical plant, everyone seemed to know everyone, and everyone I met seemed very interested in me as a person. Reflecting back on it, I believe that this was because the school’s community was built on the Quaker core value that an “inner light” exists in all people.

Two things stand out from my time at Sidwell: first, many of my teachers did not follow the textbooks, and second, we spent a substantial amount of time discussing material. Ms. Reinthaler, to this day my favorite teacher, jumped around the math book in unpredictable ways and was obsessed more with what we were thinking than with the answer we wrote down. We were more likely to go outside and use a cigarette lighter shaped like a parabola or use a ruler sticking out of the board to demonstrate the z-axis than we were to do every problem in the textbook. Ms. Reinthaler’s class created a long-lasting impression on me.

Sidwell’s classes were interdisciplinary. In English, for example, we spent classes analyzing literature and looking for connections between a particular literary work and related social topics. We looked at what The Canterbury Tales had to say about the role of women during Chaucer’s time; reading Native Son led to a tearful discussion on race relations at the school. Science classes, beginning with biology, included labs and the use of Excel and Word to write lab reports because “that is what scientists did.”

Teaching to the tests

When I first entered the classroom as a teacher in the New York City (NYC) public schools, I expected to teach my students the same way I had been taught at Sidwell. That approach didn’t work. The world of teaching and learning in the schools where I was assigned was drastically different from the elite world of Sidwell Friends. Not apples and oranges different. Apples and rhubarb different.

During my first two years, I taught at a School Under Registration Review – identified by the New York State Education Department as a school most in need of improvement – where I struggled to create a classroom where my students would engage in large-group conversation. During an eleventh-grade unit on The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, I would ask my students to categorize and compare what happened to Huck when he was on the shore versus when he was on the river. I was often met with silence, or “Mister, why don’t you just tell us the answer so we can go on?” I was also astonished that my kids lacked literacy and writing skills.

Despite my belief in the importance of discussion, feedback from my assistant principal and colleagues required that I change my practice. I was told that “for the sake of the kids,” my lessons needed to be connected to the New York Regents exams, statewide standardized tests required for high school graduation. The teacher regarded by my assistant principal as the best English teacher at the school started every class with an exercise taken directly from the exam: providing a “critical lens” quote for students to interpret, agree with or not, and provide two pieces of literature that supported the interpretation. I faced a dilemma: I believed that I needed to teach my students the way I was taught, but I understood that failing to prepare my students for the Regents exams would amount to professional malpractice and prevent kids from graduating.

During the next stops of my NYC teaching career – which included a large comprehensive high school with a low graduation rate and a history of violence, a struggling middle school in one of Brooklyn’s poorest neighborhoods, and a small high school that selected its students in part based on standardized test scores – my teaching centered around the role of standardized tests. While teaching at the struggling large comprehensive high school, which would eventually be closed after being named one of the most persistently violent in the state, I was told by colleagues to make sure that I mentioned the Regent’s exam during an observation or the principal might rate the lesson unsatisfactorily. When presenting students with context for a literary text, I created read-aloud passages on which my students were to take notes and answer questions. All my tests and exams were mini versions of the Regents exams and featured the critical lens essay.

While I did my best to avoid teaching to the test, the reality was that I became focused on making sure that the exam would not prevent my students from attending college. When my students graduated, I always counseled them to make sure they visited their new college’s writing center, since I knew that many of them graduated from high school only able to write a critical lens essay.

Creating a school where we would not teach to the test

After spending twelve years teaching English, I seized an opportunity to create and serve as principal of a new high school that would connect students to a possible career, but also focused on classroom discussion. I partnered with the Institute for Student Achievement (ISA) because there was a philosophical connection between my vision for my proposed school and ISA’s emphasis on career and technical education. The collaboration resulted in the Institute for Health Professions at Cambria Heights (IHPCH), a high school that opened in 2013 with 56 ninth-grade students and has grown to 420 students in four grades.

During summer professional development with the founding teachers, I stressed that student inquiry, interdisciplinary connections, and discussion were essential to developing the school I envisioned. Although I had hired teachers with this vision in mind, it proved very difficult to change the mindset of test preparation among New York teachers. I showed a video of a Living Environment class (the state-required biology course), where a teacher used an excerpt from a science fiction novel to facilitate a discussion. When I asked my teachers how this video could serve as a model for the work that we would do with our students, the Living Environment teacher asked, “How am I supposed to spend several days discussing this book when I have to cover the Living Environment curriculum so the kids have a chance on the Regents exam?”

Similar complaints came from teachers in other departments. “It would be great,” they argued, “to focus on specific historical time periods or core mathematical concepts,” but the need to ensure that our kids passed the exams was the proverbial elephant in the room. The very same dilemma I experienced as a teacher would become the defining challenge in my new role as a school leader.

This situation would change when one of our school’s coaches connected us with the New York Performance Standards Consortium (see sidebar). This introduction led my school’s founding staff to make a decision that would fundamentally change the trajectory of our school’s development.

IMPACT OF IHPCH’S TRANSITION TO THE CONSORTIUM (ANN COOK & GARETH ROBINSON)

Becoming a Consortium school has had a particularly powerful impact on the role teachers play at IHPCH, and faculty ownership of the process is regarded as critically important. To support teachers in the transition, we attended summer workshops held by the Consortium, visited and observed Consortium teacher practice, and participated in the Consortium’s annual conference. The main form of support I gave my teachers was freedom to experiment with both the “what” and the “how” in their teaching. Our emphasis on inquiry-based teaching and learning and discussion-based classrooms resulted in a strong focus on pedagogy and positive rates of teacher retention. Instead of narrowly focusing on anticipated questions on a standardized test, IHPCH teachers plan curricula for students that ensure that interim assessments (pre-PBATs) are aligned to the same skills students will need to complete the more complex PBAT challenges. For example, one of IHPCH’s graduation-level science PBATs is a project where students engineer a catapult using their knowledge of projectile motion and mass. Science teachers collaborated to ensure that in physics classes, students would gain experience contextualizing a design problem, critiquing the process, testing a design prototype, evaluating the design, and finally, defending their work in an oral presentation.

HISTORY OF THE NEW YORK PERFORMANCE STANDARDS CONSORTIUM (ANN COOK)

The Consortium was created by a waiver in 1995 by the New York State Education Commissioner. The waiver allowed Consortium schools to graduate their students using a system of performance-based assessments (called PBATs or portfolio assessments) in lieu of four of the five Regents exams.

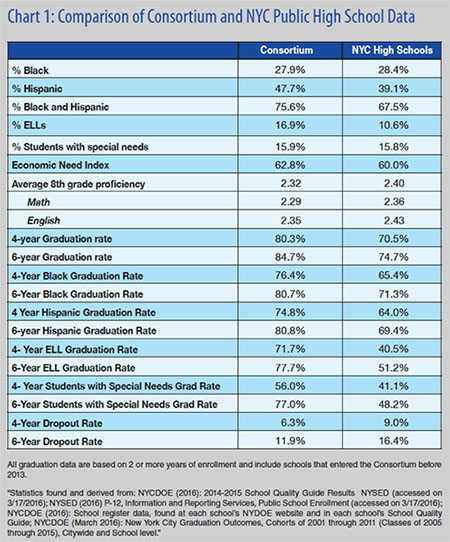

Today, nearly 30,000 students attend the Consortium’s thirty-nine public high schools in New York City, Rochester, and Ithaca. Comparative data have demonstrated these students’ success, with particularly significant results for four- and six-year high school graduation rates for students of color (see Chart 1). NYC Consortium schools serve a higher percentage of African American, Latino, English language learner (ELL), special needs, and low-income students than the city’s public schools as a whole, and Consortium students enter high school with lower math and English test results than city-wide averages. Yet these same students graduate at higher rates than the city average, with a four-year graduation rate for ELL students that is 31 percentage points higher than the city average.

Overall, the Consortium schools have a lower dropout rate than the city schools. Statistics from the New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE) show that 83 percent of Consortium students met or exceeded NYC DOE targets for enrollment in college a full eighteen months after graduation, compared with 59 percent of students in the rest of the city. (Individual school data is available at the NYC DOE website.)

A Spencer Foundation–funded study of teachers who moved from test-based schools to Consortium schools found that teachers in the performance-based assessment environment strongly believe they “learn more about their student’s academic needs” and are able to “teach more creatively” and teach “more socially just” and “culturally relevant” curriculum. Researchers also reported that teachers in their second year of teaching in performance-based assessment schools felt their students were “more engaged in school” and that using PBATs made “their students more interested in learning” (Hantzopoulos, Rivera-McCucthen & Tyner-Mullings 2016).

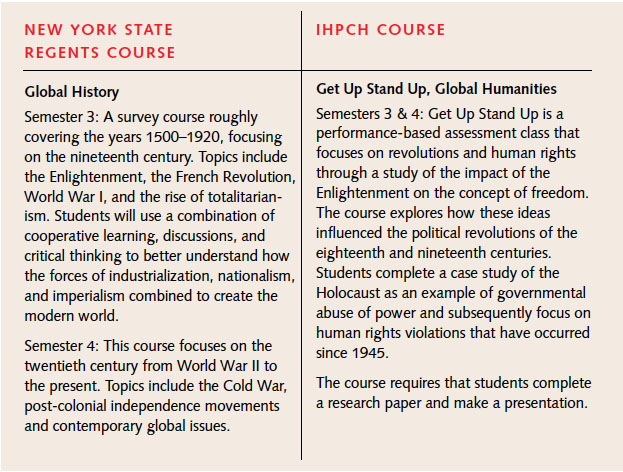

The transition toward performance-based assessment and away from Regents exams has been both humbling and empowering for IHPCH teachers: humbling because any instructional or curricular problems could not be blamed on the need to prepare students for the Regents exam; empowering because teachers have created classes that engage students in ways that are not possible when the Regents exam is the summative assessment. Compare, for example, a global history course description offered at a nearby high school with one offered at IHPCH.

Impact on students and parents

After the school’s first year, which had included students taking Regents exams, the staff announced that the school would be joining the Consortium and making a transition away from the Regents exams. In presenting this decision to parents and students, the staff emphasized that many of the skills staff wished students to develop, practice, and strengthen could be realized through performance-based assessment, including analysis, modeling possible solutions, strategizing, building evidence-based arguments, oral and written communication, subject-area competence in health care, innovation, creativity, collaboration, revision, and goal setting. Unlike standardized tests, PBATs also allow for instructional coherence and differentiation in the classroom.

The initial reaction of the students to the transition was a mini celebration. They were excited that we had chosen what they thought was an “easier” path to graduation that did not involve the Regents exams. We cautioned students that this work would be difficult and even included the challenging nature of PBATs in our recruiting talks to parents. Although prospective parents said they recognized similarities between the PBATs and undergraduate or graduate work, they were concerned. They simply could not believe that colleges would accept their children without Regents exam scores. After all, as graduates of New York State high schools, most of our parents had themselves taken Regents exams. In order to better understand the impact of our assessment system on our graduates, we intend to create an email alumni group so that we can track their successes and struggles in college, which will provide us with more concrete evidence for future discussions with parents. During our school’s second full year, we implemented the use of presentations of learning, which evolved into pre-PBAT work.

During these presentations, many students asked if we could go back to being a Regents school because “the presentations of learning were asking them to do too much reading, writing, and discussion.” There were tears in the hallway and cries of “How can we get all of this work done?” After our physics graduation-level PBAT was given to our first graduating class in January 2016, one student who had failed both the Algebra I and Living Environment Regents exams but passed the physics PBAT said that although PBATs were more work than Regents, they were more interesting and meaningful because the assessment, an engineering project, was more than simply answering questions on paper.

The transformation from a Regents-driven school to one focused on inquiry-based teaching, discussion, in-depth investigation, and oral presentations is certainly a challenge for both students and staff, but I believe we are on the right track.

Utilizing the Consortium’s student focused, practitioner-directed system of assessment doesn’t immediately transform classrooms into dynamic centers of learning, but, crucially, it allows us to shift our expectations of children from test-takers to active learners, showing that when given the tools and the opportunity, all students can engage in the level of discourse that I first experienced at Sidwell Friends.

Hantzopoulos, M., R. Rivera-McCucthen, and A. Tyner-Mullings. 2016. “In Transition: How PBATs Shape Instruction and School Culture.” Unpublished draft of study in progress, funded by the Spencer Foundation and Vassar College.