A Place-Based Process for Reimagining Learning in the Hawaiian Context

Leaders from the Office of Hawaiian Education reflect on their process in developing a culturally responsive assessment framework rooted in Hawai‘i’s indigenous context, values, and beliefs.

What would an educational system centered on core Hawaiian values look like?

The Office of Hawaiian Education, established by the Hawai‘i Department of Education (HIDOE) in 2015, has been exploring this question through a community-based process that differs significantly from typical Western approaches to policymaking. Often, policymakers use a top-down approach to policy formulation and implementation that focuses on outputs, outcomes, and impact. In contrast, Hawai‘i’s new outcomes framework emphasizes community and indigenous values, knowledge, and shared ownership. This values-based approach is embedded in every aspect of the Office of Hawaiian Education’s work – from the outcomes framework, to the implementation process, to the way they speak about their work. Hawai‘i’s unique emphasis on community, adaptability, and teaching to the whole child contains transferrable lessons for other policy efforts and contexts.

The Office of Hawaiian Education, established by the Hawai‘i Department of Education (HIDOE) in 2015, has been exploring this question through a community-based process that differs significantly from typical Western approaches to policymaking. Often, policymakers use a top-down approach to policy formulation and implementation that focuses on outputs, outcomes, and impact. In contrast, Hawai‘i’s new outcomes framework emphasizes community and indigenous values, knowledge, and shared ownership. This values-based approach is embedded in every aspect of the Office of Hawaiian Education’s work – from the outcomes framework, to the implementation process, to the way they speak about their work. Hawai‘i’s unique emphasis on community, adaptability, and teaching to the whole child contains transferrable lessons for other policy efforts and contexts.

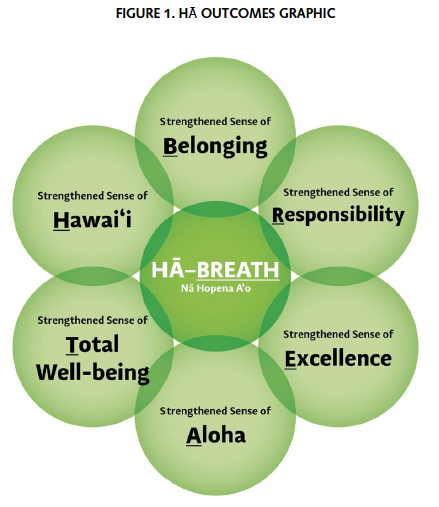

To understand Hawai‘i’s policy landscape, we must first understand its history. The Hawaiian education system has not always reflected the rich diversity of its population, which encompasses a broad range of cultures, languages, races, ethnicities, and belief systems. Since the 1970s, however, a Hawaiian cultural renaissance has increased the influence of Hawaiian values on policymaking (Wilson 1999). In 2012, the Hawaiian Board of Education formed a working group to strengthen Hawaiian values in the public education system. Educators and community members emphasized the importance of building from the strengths of Hawai‘i, leading the working group to develop Nā Hopena A‘o (“HĀ”), a framework rooted in Hawai‘i’s indigenous context. HĀ (pronounced “hah”), meaning “to breathe” or “breath” in Hawaiian, supports a holistic learning process in which outcomes are meant to be demonstrated by everyone within the school system – including students, teachers, and administrators. The Hawai’i Board of Education approved the HĀ outcomes in 2015, and the state is currently engaging in a two-year pilot with the Assessment for Learning Project (ALP) to develop a valid and culturally responsive assessment framework through a process of mo‘olelo [generative storytelling] that draws on the insights, experience, and wisdom of students, educators, families, and community members.1

Christina Kuriacose and Meaghan Foster from the Center for Collaborative Education (CCE) spoke with Kau‘i Sang, director of the Office of Hawaiian Education, and Jessica Worchel, Nā Hopena A‘o special projects manager, to learn more about their journey guiding the HĀ framework to implementation and the values that have informed their process. In speaking with them, it became clear that they are treating the new policy as an invitation rather than a mandate, allowing schools and communities to choose how and when they incorporate the HĀ framework into their own context. The Office of Hawaiian Education is deliberately not telling schools what a successful end result will look like; instead, the Office trusts that if schools and communities follow an inclusive, values-based process, they will be able to implement the framework successfully in their own contexts.

To start, we would love to hear the story of the development of HĀ from both of you, and how the HĀ framework differs from other student outcomes frameworks.

Kau‘i: The big question we asked was, “What kind of vision, beyond academic achievement, does HIDOE have for its public school graduates?” With this question guiding us, our task was to ground our learner outcomes in Hawai‘i the place. The general learner outcomes that we were implementing were something you could find in Anywhere, USA. They didn’t tell a story about what it meant to be someone who came from Hawai‘i, lived in Hawai‘i, and was touched by Hawai‘i. Of the twelve of us in the working group, only four of us could speak Hawaiian fluently, but the group in general was attracted to statements that were drafted in Hawaiian.

We took those initial ideas and went through a year-long refinement. We held meetings with educators and community members to discuss what an outcomes model should encompass in order to generate a collective vision. The discourse allowed us to honor the input process and gave us the space to learn how we could strengthen the overall system, piece by piece. With input from all stakeholders, we landed on our final draft in November of 2014, with six core concepts (see Figure 1.)

Jessica: At one of our meetings to get input, the state superintendent stands up and asks, “How can we expect our students to have these outcomes if our system isn’t modeling them? And, more personally, how can I expect my staff to do it if I’m not modeling these outcomes as a superintendent?” That really shifted the conversation from just focusing on students to lifting the new set of expectations up to be system-level outcomes.

Kau‘i: We looked to the indigenous culture to understand how we might shift the whole system. There are so many strengths of Hawai‘i. It is one of the most environmentally diverse places on the planet, and its people are also incredibly diverse. We are on an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, so we recognize that we must depend on one another and mālama [take care] of our people and land, because we are all connected and have limited resources.

This perspective influences our HĀ outcomes to focus on the conditions and learning environments that lead to strengthening HĀ, as opposed to on how to measure an individual’s HĀ. They are about kākou – collective success versus individual success.

Jessica: HĀ is different from other outcomes frameworks because it is not just focused on students. Before someone can train others, they must look at how the outcomes resonate for themselves. You can’t force HĀ on others, but you embody and model to strengthen HĀ for yourself and others.

What would you like a graduate to know/believe/embody within your system?

Kau‘i: Coming from a native Hawaiian family myself, the importance of accountability to the things that you belong to, to the people that you belong to, is sort of a high-level standard – it’s an expectation which we call ‘Ohana. ‘Ohana is really what we hope for when we see our graduates move out of the K–12 context into their adult lives – that they hold space for others. If you take a look at each of the HĀ statements, they’re really aspirational, and they show up differently depending on the context. What we hope for the graduates – and beyond just the graduates, for all of us – is that they will have the ability to exhibit these outcomes in diverse environments.

Jessica: How do we take care of ourselves as a mental entity, physical entity, emotional entity, and a spiritual entity? How do we allow for us and our education system to honor the whole person, and not just the academic person? Hawai‘i is our place. Wherever we are, that land has something to teach us.

You looked to indigenous culture to help inform this systemic shift. Was that a natural progression, or was there a decision point where the team chose that as a key priority?

Kau‘i: What we are finding is that the doors open when we start to lean on the strength of Hawai‘i first. To your question on whether we intentionally moved to ground the work in indigenous education philosophy, I don’t think we did that initially.

The first iteration of the change in the general learner outcomes policy came out as a very soft translation of typical outcomes in English into Hawaiian. When that iteration was submitted, the board chair and the deputy superintendent pushed back and said that the task may not be to start with what was already there but to create something from Hawai‘i first. Anyone who speaks a different language recognizes that there is a much deeper culture represented in that language and it cannot just be translated one to one. By starting with the Hawaiian language, we started from a different perspective, and therefore the outcome was different.

Jessica: I think that’s something that’s special about the Hawaiian context. Starting with ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i [Hawaiian storytelling] and honoring the values of Hawai‘i created a more collective outcomes model. The outcomes also include ‘ōlelo noe‘au, or Hawaiian proverbs, to honor the wisdom of our kūpuna, or elders and ancestors.

HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE IMMERSION PROGRAM

Efforts to revitalize the Hawaiian language began in the mid-1980s, when a network of private Hawaiian immersion preschools called ‘Aha Pūnana Leo [the language nest] successfully lobbied the state to reverse the colonial-era ban on the language. In 1987, HIDOE began its own network of public Hawaiian language-immersion schools, called Ka Papahana Kaiapuni. Today, fifteen traditional public schools and six charter schools educate some 2,000 of the state’s public school students in Hawaiian. However, challenges have emerged in creating policies that are effective in both immersion and Western schools, particularly around assessment.

Indigenous cultures place high value on ancestral wisdom. Indigenous perspective also values diversity of ideas, so the final outcomes model, while creating a shared framework and language, allows for a multitude of interpretations based on context. Because of the process being so inclusive and the honoring of the ‘ike kūpuna [ancestral knowledge], it is our kuleana [responsibility] to share HĀ.

Can you speak more about the influence the community has had on the development of HĀ?

Jessica: Public education was initially designed to separate students from the community – whether it is from their language, culture, or community “teachers.” Children would arrive at the school and be asked to leave their community at the door. We are now acknowledging that the community is just as important – if not more so – to the education of the child. We want to help students ground themselves in who they are and where they come from, meaning that our teachers and staff must also become fluent in the culture and place of the community. Therefore, we must build up our community education space and create room in the system to allow for seamless access between schools and communities.

HĀ IN ACTION

Moloka‘i High School created a Pu‘uhonua Pass that allows students who are having a challenging time being in the classroom to take the pass and go out to reflect on their actions. In Hawaiian, Pu‘uhonua means “place of refuge.” The pass includes questions related to HĀ and allows students time to reflect on their conduct instead of relying on detention.

Kahakai Elementary grounded their Positive Behavior Intervention Supports in HĀ. They recently went through an all-staff orientation and are now reconsidering their essential questions and who their stakeholders are to align with the HĀ framework.

Kalihi Waena Elementary is rolling out HĀ to all teaching staff. They held a professional development day at Ho‘oulu ‘Āina, a local nonprofit that has been stewarding and sustainably developing 100 acres and is dedicated to cultural education and community transformation. The school is working to deepen their ability to have teachers use the community resources and take students out onto the land to learn.

The Campbell/Kapolei Complex Area received a Project Lead the Way grant to bring in community support to make the curriculum more culturally relevant and place-based. They are also taking teachers out to engage with the community and learn more about the native Hawaiian culture.

The new Global Youth Leadership course at Castle High School weaves together student leadership, Hawaiian leadership, and global leadership. Co-created by multiple partners, the course incorporates the vision and values of the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s Mālama Honua, the HĀ outcomes, and leadership concepts and competencies. Semester units focus on themes of home, destination, wayfinding, and Mālama Honua [to care for our Island Earth]. Students participate in indigenous and Western leadership practices, experiential learning, community engagement, global studies, and conferences

Kau‘i: In the 1990s, the Hawaiian language immersion group created a statewide consortium of parents, teachers, school administrators, community organizations, and state Department of Education staff. The group began to talk about some of the issues facing the Hawaiian language immersion program and collectively try to push on the same issues to create change. As they started to lift that voice into the system more and more, I think the current superintendent saw activism as something to be valued. It started to give the system some answers to the “how”: How do we integrate community into education decision-making? How do we share the accountability for the work that we’re responsible for, so that it’s not just one stakeholder group having to hold on to the weight of a system?

Jessica: We recently hosted a HĀ designers convening and invited teams from across the state to come together in order to learn more about HĀ, share their experiences, and plan to host community days in their region. Each team was asked to bring a staff member from a school, a student, and a community member. We are intentionally working to build and strengthen the connections with the local community and to include students so that teachers can lean on community resources. We are also planning a HĀ Summit, which will bring sixteen school-community teams together to share how they are contextualizing HĀ and determine how to strengthen HĀ within and without the HIDOE. On the planning group, we have a mix of internal HIDOE staff and external community representatives.

We also lift up folks who are not typically looked at as experts or given a voice. For instance, I did a presentation on HĀ at Maui High School, and afterwards one of the skills trainers who works with autistic students came up to me and said, “Well, I’m just a lowly skills trainer, but I would like to have a poster of the outcomes.” I looked at her and said, “You are just as important to this community as any other person in this space.” And same with our clerical staff. We also have our secretaries do presentations with us and talk about their own stories in connection with HĀ, so I think there’s another piece about how we give value to every person in this system who is contributing to our kids.

What do you see as the key attributes of a culturally responsive assessment framework in Hawai‘i?

Jessica: I think the two critical components are: (1) you have to value and honor the indigenous perspectives and indigenous ways of knowing and being; and (2) you have to trust. We honor and value the mo‘olelo [stories] of all. Through storytelling and conversation, we make meaning and ensure every voice counts. We must ensure that it is not only one story being told. Currently, the assessment framework is still in the design phase, but I think a lot of folks have difficulty when we talk about multiple pathways with assessment because they expect we have federal regulations and state regulations and a very complex law and compliance system.

BUILDING AN ASSESSMENT SYSTEM

HIDOE is in the process of creating a HĀ Assessment Framework through a pilot with the Assessment for Learning Project. The first step of the pilot was a listening tour to generate ideas for developing an assessment system grounded in the HĀ framework. The pilot team is currently testing and refining potential tools and processes that have emerged through their mo‘olelo [generative storytelling] process. They hope to complete an expedited second round of testing the tools by mid-summer 2017.

The pilot has provided the HIDOE with the time and space to learn from the Hawaiian context and community. They have learned that it is important to shift the emphasis from assessing an individual student’s achievement, to instead assessing the learning environment and the components that enable students to demonstrate HĀ. Unlike an individual accountability model, the model that has emerged is focused on identifying optimal conditions for building HĀ within learning communities. A picture of a HĀ evaluation system is beginning to take shape as the pilot team continues to seek community feedback, iterate, and re-incorporate Hawaiian wisdom and values.

Kau‘i: In a town like Waipahu, a town with a large population of Filipino students, they can better design content for their context than a Hawaiian language immersion school that has 99 percent Hawaiian students. The outcomes framework – even though it’s starting off with that indigenous mindset – really is trying to shift the system. In the context of indigenous cultural practice in Hawai‘i, the ali‘i, or chief, actually had a group of advisors who would advise him on the best way to treat the community and take care of the community. It wasn’t his individualistic dictator-style of relationship, but it was really around, “How do I make sure the decisions we collectively make create this sense of lōkahi, or balance, in our ecosystem?” We are trying to lift up that practice and put it into the educational context where this idea of multiplicity allows us to create a much more balanced assessment ecosystem.

It seems like a lot of the values you’re speaking about run so counter to current assessment practices, which emphasize a single path to demonstrate knowledge and prioritize individual success instead of collective success. How are you currently talking about the ramifications of that shift with educators?

Kau‘i: We think that readiness is a huge factor as we introduce conversations, because it is quite a huge shift in thinking. If you take a look at the entire system itself and the 280 schools and the 180,000 students (including our public charter schools), the range is huge in terms of readiness. We have folks who are absolutely ready, and we have folks in schools who are walking in the opposite direction, and there are a bunch of people that fall in between. When we go out and we share the story, we’re asking a particular question about the context, and we’re trying to design the presentations and the conversations and the work around that context so that they can see themselves in the work.

Jessica: In terms of the rollout of HĀ, we only go to places where we’re invited to talk about HĀ. It’s really a grassroots approach. Instead of us going out and doing all this big push or branding or messaging and requiring people to participate, we’re allowing folks to ask for an orientation or attend a convening. They invite us into their space or they actively choose to be in our space. They then go back and share with others to build buy-in to the idea of shifting and intentionally incorporating the HĀ outcomes. This way, we know there’s already a level of readiness. While there are guiding indicators, we ask people to develop what HĀ means in their context. HĀ is about empowering people to define the outcomes and indicators associated with those outcomes for themselves, which builds ownership and accountability. We’re shifting our perspective at the state office from being this compliance-driven entity, simply mandating changes in school policy, to a support network.

The guiding principle that we always come back to: Is this best for your students? Are you seeing them inspired? Are you seeing them engaged? Are they learning? As an educator, you know when you see that and feel that, and it’s not necessarily a test score.

Concluding with what’s best for students and student engagement feels really fitting. Anything else you want to add?

Jessica: HĀ is how you address the achievement gap. You actually create a system that creates the conditions for success for all kids instead of trying to cram those kids that aren’t currently being served into a mold they don’t fit. How can you create an education system that really lifts up and values what our kids bring? They’re so unique and they’re so talented. We need to create that space for them, to support them.

1 The Assessment for Learning Project (ALP) is a multi-year grant program and field-building initiate inviting educators to fundamentally rethink the roles that assessment should play in advancing student learning. See the ALP website for more information on their partnership with the HIDOE.

Wilson, W. H. 1999. “The Sociopolitical Context of Establishing Hawaiian-Medium Education,” in Indigenous Community-based Education, edited by S. May, pp. 95–108. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters Ltd.