Teachers, Micro-Credentials, and the Performance Assessment Movement

Micro-credentials, a new form of personalized professional development for teachers, offer a unique solution to the challenge of training school staff to design and implement performance assessments.

Micro-credentials move professional development toward a more personalized learning system for teachers in which you can go at your own pace and the work is job-embedded. – Tony Lementowicz, Westerly (RI) High School teacher

Deeper learning outcomes for all students – and more accurate and authentic measures of them – have become the school reform coin of the realm. If this new era of performance assessment is to be successful, we need teachers to serve as assessment leaders who can help to build the literacy and capacity of every school to design, field-test, score, and refine high-quality performance tasks.

Teachers are the cornerstone of successful performance assessment initiatives. They generate, validate, administer, and score the performance assessments that are used (Tung & Stazesky 2010). Teachers need more support and training in order to fill this important role in performance assessments, yet most professional development for teachers has been found to be ineffective. Too much of the time, district central offices determine professional development focus and delivery, all but guaranteeing teacher dissatisfaction in meeting their needs and interests. A recent study points to the woeful state of our nation’s $18 billion public education professional development enterprise. The researchers found that “one-shot” workshops are the most prevalent form of professional development (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 2014). This one-time professional development has been found to “neither change teacher practice nor improve student learning” (Gulamhussein 2013, p. 3). Fewer than 30 percent of teachers choose most or all of their professional learning opportunities, and only 7 percent of teachers reported that their schools have strong collaboration models (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 2014).

Teachers are the cornerstone of successful performance assessment initiatives. They generate, validate, administer, and score the performance assessments that are used (Tung & Stazesky 2010). Teachers need more support and training in order to fill this important role in performance assessments, yet most professional development for teachers has been found to be ineffective. Too much of the time, district central offices determine professional development focus and delivery, all but guaranteeing teacher dissatisfaction in meeting their needs and interests. A recent study points to the woeful state of our nation’s $18 billion public education professional development enterprise. The researchers found that “one-shot” workshops are the most prevalent form of professional development (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 2014). This one-time professional development has been found to “neither change teacher practice nor improve student learning” (Gulamhussein 2013, p. 3). Fewer than 30 percent of teachers choose most or all of their professional learning opportunities, and only 7 percent of teachers reported that their schools have strong collaboration models (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 2014).

On the other hand, research suggests that the most effective professional development is contextualized to the specific needs of teachers, where they have opportunities to take ownership of their professional learning (Berry 2016). Professional development needs to be of a granular size so that teachers can engage in it during a hectic school year. Such a model often sits outside most university graduate courses, district-delivered and batch-sized professional development, and one-shot conferences.

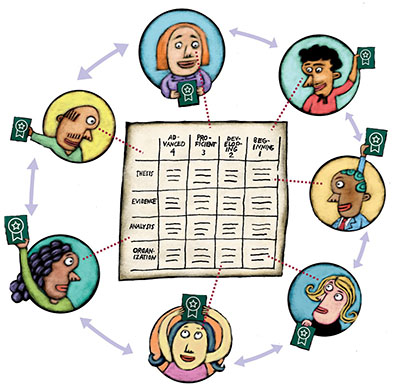

It is within this space – placing teachers at the center of designing their own professional development, coupled with the need for teachers to build performance assessment literacy and capacity – that performance assessment micro-credentials come to the fore. Micro-credentials for teachers are competency-based, personalized, small-scale professional development modules that are suited for anytime/anywhere learning and allow teachers to show what they can do, not only what they know. Micro-credentials change the face of teacher professional learning to move away from one-size-fits-all efforts to customized, just-in-time learning that leverages personal desires for professional growth.

Professional development for performance assessment literacy is uniquely suited to micro-credentialing. Both require teacher agency and collaboration, and the fact that micro-credentials can be pursued by individuals rather than schools or districts allows teachers to take the lead in scaling up to school-wide performance assessments.

SOME BACKGROUND ON MICRO-CREDENTIALS

The idea for micro-credentials began with “digital badges,” which first gained recognition as a means to personalize student learning; they “are designed to make visible and validate learning in both formal and informal settings, and hold the potential to help transform where and how learning is valued” (MacArthur Foundation 2017). School districts (such as the Aurora Public Schools in Colorado) and nonprofit organizations (such as Connected Learning Alliance) are beginning to recognize digital badges, not just seat-time requirements (or a required number of hours for courses), as markers of student achievement. By enabling students to demonstrate proficiency over identified competencies (or learning targets, including dispositions such as collaboration and communication or skills as wide-ranging as set design or research skills), they are better able to track their progress in gaining tangible and usable knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

Now the personalized learning movement is reaching teachers. Over the past two years, Digital Promise, a nonprofit seeking to accelerate innovation in education, has been building an ecosystem for advancing the design, development, and implementation of micro-credentials for educators. Digital Promise has partnered with technology companies to create online professional development platforms to facilitate the process of an educator selecting a micro-credential and submitting evidence to earn it.

As of fall 2016, over forty content partners have developed more than 400 micro-credentials – organized in “stacks” – to address a variety of educator skills and competencies. Micro-credentials hone in on a wide variety of competencies, from highly granular aspects of teaching (such as a Checking for Understanding stack issued by the Relay Graduate School of Education) to a bold brand of teacher leadership (such as the Teacher-Powered and Virtual Community Organizing stacks issued by the Center for Teaching Quality [CTQ]), as well as the Performance Assessment Design stacks (see sidebar) issued by the Center for Collaborative Education (CCE).

Four characteristics distinguish the micro-credentialing approach from traditional professional development systems:

- Competency-based. Micro-credentials focus on evidence of teachers’ attainment of actual skills and abilities, not on the amount of seat time they’ve logged in their learning.

- Personalized. Teachers select micro-credentials to pursue on the basis of their own needs, their students’ strengths and challenges, school goals, district priorities, and/or instructional shifts. They identify specific activities that will support them in developing each competency.

- On demand. Micro-credentials are responsive to teachers’ schedules. Educators can opt to explore new competencies or receive recognition for existing ones in any manner and time span they choose. They then upload evidence of proficiency using an online system.

- Shareable. Educators can share their micro-credentials across social media platforms, through email, and on blogs and résumés. As a result, micro-credentials can emerge as shareable currency for professional learning.

CENTER FOR COLLABORATIVE EDUCATION’S MICRO-CREDENTIAL PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT STACKS

- Basic Performance Assessment Design: design of performance assessments; design of competency-based rubrics; and performance assessment validation.

- Advanced Performance Assessment Design: calibrating scoring among teachers; looking at student work; assessing habits, skills, and dispositions; and using performance assessments to provide formative feedback.

- Leading a Performance Assessment Community: modeling processes for educator collaboration; facilitating performance assessment protocols in professional learning communities; and communicating and advocating for performance assessment policies at the school- and district-levels.

Each micro-credential in the Digital Promise ecosystem includes six parts: competency, key method, components, research and resources, submission criteria, and scoring rubric. Teachers assemble and upload a mini digital portfolio, which might include a video of a lesson, student work, classroom observations, teacher and student reflections, and/or other documentation of teacher learning. Trained assessors – individuals whom the issuing organization has qualified to review the evidence – examine the teacher’s submission against a rubric. The issuing organization then deter- mines whether the teacher should be awarded the micro-credential. (Since Digital Promise is still in the early stages of developing the micro-credential eco-system, the cost model for issuing micro-credentials is still under development.)

Creating performance assessment micro-credentials

In the spring of 2016, CCE and CTQ launched the Performance Assessment for Learning (PAL) initiative, with support from the Center for Innovation in Education at the University of Kentucky and Next Generation Learning Challenges. In particular, we sought to test the power of micro-credentials in promoting teacher leadership to drive adoption of school-wide performance assessment systems that lead to personalized, proficiency-based learning and assessments for students.

We launched our initiative in partnership with the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE), which has a ten-year history of promoting proficiency-based education. A committee of five teachers worked with CCE and CTQ staff to design three “stacks” of performance assessment micro-credentials, with each stack containing three separate micro-credentials (see sidebar).

In the 2016-2017 school year, we brought together fifty volunteer teachers from a handful of schools, with the premise that a team of teachers pursuing performance assessment micro-credentials would be better positioned to effect school-wide change than individual teachers. These teachers came together for a half-day orientation, then worked with CCE staff individually to select their preferred micro-credentials and develop a plan of professional growth to attain them, including identifying the evidence they would collect. CTQ created a virtual community for participants to share and learn from each other.

CCE sees growing demand for its performance assessment micro-credential as states and school districts seek to build teacher capacity to transform the ways student learning is assessed. Early adopter states are making strides toward embedding micro-credentials in their teacher certification renewal processes; for example, recently enacted legislation in Illinois allows “teachers and administrators in the state to pursue different types of professional development that can include micro-credentials” (Center for Teaching Quality and Digital Promise 2016, p. 14). Simultaneously, early adopter districts, such as Kettle Moraine School District in Wisconsin, are integrating micro-credentials into teacher salary scales and teacher leader roles. As stated on their website, “Micro-credentials for Kettle Moraine educators . . . provide pathways to specific skills and habits that closely align to the District’s mission and goals, as well as each educator’s professional goals.”

Early lessons: What are teachers saying about micro-credentials for performance assessment literacy?

If micro-credentials are intended to be a form of professional development that empowers teachers, then our early efforts with the PAL stacks suggest we are on the right track. At a fall 2016 forum highlighting the work of Rhode Island high schools in implementing new assessment systems, teachers piloting performance assessment micro-credentials shared their insights about engaging in learning and building a body of evidence to demonstrate proficiency over chosen micro-credentials. Several ideas emerged from listening to them:

Teachers view micro-credentials as a means to take control over their own professional development, shaping it in ways that are meaningful to them. One teacher, told us that the PAL stack helped him to “pursue his own goals,” while a second pointed out that micro-credentials “help teachers clarify what is important to them.”

Micro-credentials are viewed as a valuable means for teachers to improve their practice. A teacher noted that he had “hit a wall” with his classroom teaching. He felt like he was not getting better at his craft, and the PAL stack offered “a clear path for setting goals and improving his practice.” A high school teacher asserted, “Through engaging in these micro-credentials, I have seen the power in creating good assessments and how it improves learning for students and drives my instruction.”

Teachers value the opportunity to individualize their professional growth but also drive teaching as a collective practice. An administrator of an adult education program told us, “Micro-credentials are a perfect way to present individual learning opportunities for our professionals.” Several colleagues pointed out that their most profound utility may be in driving a collaborative process and a means to improve team-wide practice. For example, a teacher pointed out that the CCE and CTQ process of engaging colleagues in micro-credentials created “an effective formal structure for a team of teachers to ensure integrity in the process of professional growth.” Another high school teacher noted the power of the micro-credentials in defining the what and how of her professional learning community: “The micro-credential process has really focused us in a way that helps us re ect on things. For example, we are using [CCE’s] Quality Performance Assessment tools to see what we are already doing as a team and what gaps there are in our knowledge and experience.”

Educators want states and districts to formally recognize micro-credentials as a credible form of professional development. While embracing the potential power of micro-credentials, educators were also keenly aware that, in order for them to be widely accepted and used, micro-credentials need to be integrated into district and state systems so that they become a viable path for teacher professional growth. As the adult education administrator asked, “Is the state going to be accepting micro-credentials as a valid credential – and can I use it for recertification?” One teacher was even more specific:

There needs to be some form of currency to incentivize teachers to use micro-credentials. This is not about seat time – it is about real learning. There are some teachers who want leadership opportunities, and micro-credentials are a way of demonstrating competencies and earning badges that schools and districts [should] value.

The teachers we interviewed are hungry for a different form of professional development – and are seeking tools and processes to spur ownership of their own learning. A recent national survey, commissioned by Digital Promise, found that nearly three in four teachers are pursuing “informal” learning (e.g., participation in online communities like the CTQ Collaboratory or Teaching Partners) that satisfies their quest to improve (Grunwald Associates & Digital Promise 2015). At the same time, we recognize that if micro-credentials are going to gain currency as a powerful tool for teacher-driven professional development and new performance assessments, states and districts need to create incentives and opportunities to leverage the time teachers have to learn.

PAL micro-credentials and next-generation reforms

The recent passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) presents district and state leaders with new opportunities to rethink strategies and funding for accountability systems as well as avenues for teachers’ professional learning and growth. States have greater latitude to redefine their accountability metrics and to include a greater range of measures as part of the system of oversight and reporting. As Darling-Hammond and colleagues have noted, new accountability systems should “include annual determinations of student achievement and growth through locally designed and state-validated systems of performance assessments” (Darling-Hammond, Wilhoit & Pittenger 2014). In such systems, a network of practitioner “assessment experts” will be needed to support schools. Each school would have two to five of these teacher assessment experts to lead faculties in the design, validation, administration, and calibration of robust, curriculum-embedded performance assessments.

With Darling-Hammond’s words in mind, to bring performance assessment micro-credentials to the fore, states and districts must take several critical steps.

States need to:

- establish micro-credential attainment as a means of certification attainment and renewal;

- invest federal professional development dollars in creating well-facilitated, cross-district networks (virtual and face-to-face) for teachers to build performance assessment expertise; and

- develop incentives for districts to reallocate professional development dollars to give teachers more choice in demonstrating their pedagogical and leadership skills via micro-credentials – with a premium on high-value competencies related to next-generation performance assessments.

Districts need to:

- create performance assessment teacher leader roles, in which teacher leaders continue to teach yet are also given time and space to build performance assessment expertise with other faculty;

- reinvent professional learning communities so that teachers have time and agency to use micro-credentials to document impact and spread best teaching practices;

- insert into salary scales the attainment of micro-credentials as a primary means of demonstrating professional growth; and

- prepare administrators to work with teachers in using the evidence from micro-credentials to spread teaching expertise.

In a relatively short period of time, micro-credentials have shown promise in enabling a more personalized, effective method of promoting teacher professional growth. Such a model is critically important in transitioning to new accountability systems that rely upon teachers on the ground to be designers, validators, and scorers of high-quality valid and reliable performance assessments. As we re-envision accountability systems to better serve student learning in complex and authentic ways, micro-credentials are an important vehicle to build the necessary teacher capacity to lead the performance assessment movement.

Berry, B. 2016. Transforming Professional Learning: Why Teachers’ Learning Must Be Individualized – and How. Carrboro, NC: Center for Teaching Quality. .

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. 2014. Teachers Know Best: Teachers’ Views on Professional Development. Seattle: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Center for Teaching Quality and Digital Promise. 2016. Micro-credentials: Driving Teacher Learning & Leadership. Carrboro, NC: Center for Teaching Quality and Washington, DC: Digital Promise.

Darling-Hammond, L., G. Wilhoit, and L. Pittenger. 2014. “Accountability for College and Career Readiness: Developing a New Paradigm,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 22, no. 86.

Grunwald Associates and Digital Promise. 2015. Making Professional Learning Count: Recognizing Educators’ Skills with Micro-credentials. Washington, DC: Digital Promise.

Gulamhussein, A. 2013. Teaching the Teachers: Effective Professional Development in an Era of High Stakes Accountability. Alexandria, VA: National School Boards Association, Center for Public Education.

MacArthur Foundation. 2017. “Digital Badges,” MacArthur Foundation website.

Tung, R., and P. Stazesky. 2010. Including Performance Assessments in Accountability Systems: A Review of Scale-Up Efforts. Boston: Center for Collaborative Education.