Identity Affirmed, Agency Engaged: Culturally Responsive Performance-Based Assessment

Performance assessments must be culturally responsive in order to truly serve the needs of students from all backgrounds.

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. . . . If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. (Zinn 2004)

I am not comfortable with categories of identity because I have witnessed the way that they are utilized to arrest the mind, detain the spirit, and even liquidate a people. Moving through the discomfort, I have come to embrace an identity as an “activist-scholar” or “scholar-activist” and to realize that identity is always a process of negotiation between how we see ourselves and how we are seen.

For the past few years, I have been active in the resistance against high-stakes standardized testing. I have always been vocal and have signed letters against the misuse and abuse of standardized testing. This defiance was triggered by the pressures placed on my son to take the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) standardized test, despite the onset of the flu. As I said then, and as I continue to believe, my children are not my only concern. The regime of high-stakes testing is deeply disturbing and inhumane for all. Educators standing before students and communities touting the virtues of these tests should be ashamed. And if they are aware that they are wrong but remain silent, they are complicit in educational malpractice.

Since then, I have organized community forums to translate educational research to the lay public and to advocate for those who choose to opt out of high-stakes testing. I have been active in local, regional, and national organizations contesting not only the test but, more broadly, the corporate agenda in education. I seek deeper thought about what is possible, to simultaneously struggle against oppressive measures while elevating liberatory practices. To paraphrase Eleanor Roosevelt, I hope to join forces with those who are lighting candles and not just cursing the darkness.

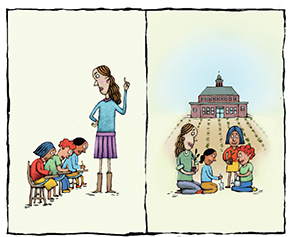

A great deal has already been stated about performance-based assessments in this issue. It has been defined in various ways and examples have been shared. I wish to engage the topic from a different angle. W. E. B. Du Bois once asserted, in light of a great deal of dialogue regarding systemic attacks on people of color, that “a system cannot fail those it was never meant to protect.” If we begin, as I do, from the perspective that institutions, including schools, are designed in the image and interests of those who rule, we must be very cautious about re-creating an educational reform environment where people of color and the poor will continue to be marginalized. If performance-based assessment is considered in the same frame as current testing regimes, which is entirely possible, it becomes just another reform fad (I don’t mean to suggest that performance-based assessment is a new one) that re-inscribes the power of systems of categorization and the conferring of rewards to those who are already materially, racially, and culturally privileged. From this perspective, performance-based assessments become another repressive surveillance technique in the lives of children and adolescents. The point is to expand performance-based assessment by rethinking its boundaries. We need to appropriate it and simultaneously remake it so that it’s not a space of colonization, a practice of arresting minds through curricular and social control, but a space that allows us to speak and act beyond the boundaries of domination.

These assessments remind me of the story of Amira,1 a six-year-old first-grader who immigrated to the United States in September 2016 and now attends a public school in a Massachusetts school district. I came to know her story through conversations with a refugee resettlement social worker, a school official involved in her case, and my own research. She was born in Syria under conditions that can only be described as an epic tragedy. Her family fled to a refugee camp in Jordan when she was three, and they were on a waiting list for asylum for three years. The refugee camp from which Amira hails is widely considered dangerous, with conditions that are especially precarious for women and children, including frequent altercations, sexual assault, and a general lack of safety. Medical services were provided only at the very basic level, and low-quality food triggered additional health care concerns while Amira was in the camp. At an early age, she witnessed a large number of civilian casualties and experienced the constant state of panic related to indiscriminate bombings. Her parents also witnessed these horrific scenes and suffered greatly as a result of U.S.-led sanctions against the Assad government. Amira did not have access to a normative school while in the refugee camp.

Teachers at Amira’s new school have noticed that when she transitions from the classroom to any area of the building, she leans and brushes against walls. She’s likely exploring her environment and sensing the difference between leaning and brushing against a tent (a common past behavior in the only dwelling she has known) and a more durable surface. She has difficulty walking in straight lines. She constantly wanders about the classroom and has been described by her teacher as impulsive. If she sees something in the room that she wants, she immediately attempts to retrieve it. Several teachers have claimed that she likely has a neurological disorder and perhaps a dis/ability related to motor development, because of her inability to hold scissors and appropriately cut paper. Part of the problem, it seems, is that her teacher is frustrated about not being able to communicate fluently with her, given that her native language is Arabic.

Teachers around Amira did not take the time to inquire about her history. Had they explored her background, they would have understood that the political, economic, and social conditions that she was exposed to would be disabling for anyone.

Her rate of English acquisition from September to November 2016, despite never having access to formal schooling, was spectacular. She could articulate primary colors, numbers, clothing items, and simple sentences in English. The greatest evidence of her intellectual acquisition and cultural immersion came in October, when she learned words such as pumpkin, Jack-o’-lantern, and Halloween. After hearing that several teachers had concerns about her progress, her parents were quite surprised. They felt that she was making outstanding progress with her acquisition of English. In addition, she has gradually learned to refrain from leaning and brushing against walls, yet it seemed that the school’s narrative of this behavior did not change.

Amira was, in fact, engaged in a natural process of cross-cultural scaffolding that invariably incorporated theorizing her relationship to her new environment. She observed a classroom alive with color and manipulatives. The disposition of the room invited exploration, and she seized it. These are luxuries that were non-existent in the refugee camp. The problem was that her teacher and the organizational behavior of the school was fraught with structures, routines, and schedules. Her exploration had to be pursued within the context of that structure and culture of efficiency. And, of course, the culture of efficiency militated against the development of a strong presence of mind with regards to cultural difference. By “difference,” I am not suggesting that the analytical focus be placed solely on Amira’s life history, but also on the ways in which our own cultural conditions get so normalized that the assumption becomes that this is the correct standard by which all others should be measured. Amira was, in short, not atypical given her history and the contexts she was navigating.

A more flexible, culturally responsive system of assessment could have captured Amira’s progress and encouraged her to continue to heal and learn. If the organizing principle behind performance-based assessments solely concerns an evaluation of the student in relation to a set of predetermined standards, many children like Amira will be at a disadvantage. Students who are indigenous, African-American, immigrant, LGBTQI, and dis/abled (to name a few markers) will be subjected to a process that requires them to adopt values and dispositions that negate their own identities. Amira’s story is a testament to the fact that children and adolescents are perpetually engaged in theory outside of the boundaries of what teachers might deem performance-based assessment. She was engrossed in imaginative play and creating her own experiential curriculum at the boundaries of cross-cultural contact.

It is therefore imperative that we continually assess and reflect on how our objectives, outcomes, and forms of evaluation relate to or negate the history of the child and the cultural, social, political, and economic context from which the child is coming. It is also important to understand that this assessment should be perpetual. Amira, for example, is dealing with another set of challenges related to her refugee status in a political environment that demands her erasure. She may not have a language to name the condition and experiences, but then again, many adults are unable to articulate it as well. What responsibility do we bear to identify and address the multiple challenges that students like Amira face, through structural and political barriers that our systems set up?

Performance or portfolio-based assessments, seamlessly integrated into curriculum and instruction and offering learners and educators plenty of opportunities to self-reflect, are decidedly powerful. The example of the New York Performance Standards Consortium is perhaps the best illustration (see article by Robinson and Cook in this issue). Yet learning outcomes are not the only positive aspect of these assessments. Performance-based assessments, at their best, assist us in the reconnection with youth and their full being. Scholar-activist Vajra Watson has been able to pair educators with community-based spoken-word artists through processes that allowed educators to develop a greater presence of mind about the material conditions of students and their cultural contexts (Watson 2013). This example of a community-based professional development of teachers has expanded to include multiple classrooms in multiple schools in Sacramento, California.

Performance-based assessments are not only necessary for engaged teaching and learning; they are imperative for life in any society committed to the ongoing democratization of civil society. They are essentially about building the dispositions and human connections essential to deep democracy.

Schools tend to be highly undemocratic spheres where various oppressive ideologies converge. A democratic political system cannot come to fruition if the institutions of that society are undemocratic, anti-democratic, or fail to (re)create the structures and conditions that lead to further democratization. Democracy flourishes when democratic cultures are the norm. Performance-based assessment, pursued correctly, is not just a technique or routine, but essentially a way of being that allows democracy to be lived on the bones.

To be more vigorous, however, performance assessments must be critical in a dual manner: in the sense of provoking imagination and in unmasking and intervening in relations of power. In the case of Amira, deeper reflection on the part of teachers concerning the relationship between knowledge and power could have unfolded. Why were teachers seeing some of her actions as deficits instead of consciously searching for the ways that she negotiated the adjustment to a new social situation? Meaningful exchanges with Amira, perhaps recorded to allow teachers to iteratively analyze her meaning-making process, might have led to an understanding that strengths were being exhibited and that those strengths should be integrated into formal assessment.

Greater thought could also be given to Amira’s current experiences, and formal lessons and assessments might be designed on virtually any topic in order to expose academic content while allowing her to further explore her conditions. For example, her story of geographic movement and space is critical to her; how might her teacher utilize this knowledge to help her arrive at a greater understanding of her story? Knowing, accepting, and understanding our stories are fundamental acts in acquiring power. A simple introduction to a world map that allows her to understand her family’s movement is a first step. And this kind of mapping activity can involve a wide range of competencies: math, language arts, art, science, and geography.

If performance-based assessment is going to be of deep value, it must integrate not only the ordinary stuff of curriculum, but also the extraordinary as exemplified by life histories like Amira’s – and the extraordinary is all around us. Teachers must learn to see what’s there, what’s not there, and theorize what should be there. Whose knowledge and experience are licensed in the very formation, implementation, and development of the assessment? What are the rules of power circulated organizationally that privilege some and marginalize others? What are the relationships between the material conditions in which youth live and performance?

How might a deeper understanding of these asymmetries provoke a more thoughtful approach to performance- based assessment? How do ideas about students’ cognitive or motivational “deficiencies” and family or cultural deficits factor into the ways in which we (re)construct these assessments? We must be provoked to a presence of mind or an ethnographic eye/I (Ellis 2003) where every uncovering of what students truly know is also an unraveling of the boundaries of our own identities, knowledge, and comfort. If what we are looking for in performance-based assessment is validation of our own ways of seeing and being, what we are in fact reproducing is cultural oppression.

Performance-based assessment is unquestionably superior to the instrumental rationality of high-stakes standardized testing and the audit culture that testing regimes inspire. It is more likely to engender opportunities to witness the un-measureable: vision, imagination, and compassion. But it must also invite students like Amira into a culture of questioning in which her identity is fully embraced and where she is able to find a way to channel her learning and emotions into positive projects that allow her to be a subject of history and not an object to be worked on. It must minimize the distance between learning and every-day life – a gap so often dismissed in schooling. It must be critical in stimulating engaged learning, and it must be critical in provoking social agency.

Plenty of examples of performance-based assessments exist. The key, I suspect, is not to pursue it as a method, but as a process that is always defined contextually. Each school, community, and socio-historical context provides unique opportunities to re-imagine these assessments and curriculum/ instruction more broadly. For example, I have spent significant time at a school in the South Bronx called The Cornerstone Academy for Social Action. The school has been incredibly effective at examining poverty across the curriculum. In my last visit, I witnessed a breathtaking discussion between seventh graders on James McBride’s The Color of Water. It reminded me of my own time as a student in doctoral seminars; the discussion was just as intense.

At the end of the series of lessons across subject areas, students spent time creating hip-hop videos and art as a culminating assessment. The Bronx, of course, was the birthplace of hip-hop, so the connection to context was powerful! Furthermore, the staff and students have organized marches to protest community-based traumas such as the news of a grand jury’s decision not to indict a police officer in the fatal shooting of Michael Brown.

The school has also organized protests against budget cuts. Students were not being prepared for life in a democracy in some distant future; they were living democracy in the moment. And, contrary to popular belief, standardized test scores did not suffer. In fact, the school has one of the highest performance rates on standardized tests in the district.

Even within the context of testing regimes, the opportunities for a more hopeful education are abundant. But if performance-based assessment is going to be of any value, it must be situated within a comprehensive process that animates educators to move beyond our own comfort zones and assist us in being more self-reflective, equity minded, and socially engaged.

1 Amira is a pseudonym.

Ellis, C. 2003. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Lanham, MD: Alta Mira Press.

Watson, V. 2013. “Censoring Freedom: Community-Based Professional Development and the Politics of Profanity,” Equity & Excellence in Education 46, no. 3:387–410.

Zinn, H. 2004. “The Optimism of Uncertainty,” The Nation (September 2).