The Negative Impact of Community Stressors on Learning Time: Examining Inequalities between California High Schools

Allocated classroom time is not the same as time available for learning – a host of economic and social stressors undermine learning time in schools serving low-income students.

This California teacher voices a concern that is sure to resonate with many educators across the country: When time is limited, it is hard to meet rigorous learning standards. The challenge is compounded in high-poverty schools where community stressors place additional demands and strains on classroom learning time. Our understanding of these challenges comes from a survey we conducted during the 2013-2014 school year with nearly 800 California high school teachers. The survey explored factors inside and outside of California public high schools that shape learning time for students and teachers during the school day and year. This survey is part of the Keeping Time project, a multi-year study of learning time supported by the Ford Foundation.1

While the number of days and minutes that students spend in classrooms is similar across most California high schools, we learned that the experience of these days and minutes differs drastically for students across different communities. We found that community stressors contribute to far higher levels of lost instructional time in high-poverty high schools compared with low-poverty or low-and-mixed poverty schools by contributing to student absences from school and to students’ difficulty in focusing on learning while in class.2

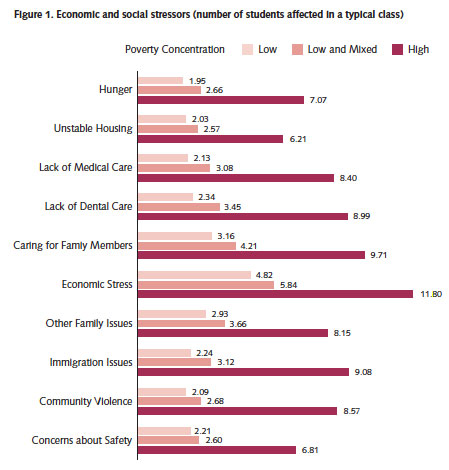

In order to quantify the impact of community stressors, we asked teachers to report how many students in one of their “typical” classes were currently affected by a set of economic and social challenges such as hunger or lack of medical or dental care. Across all ten stressors, teachers in high-poverty schools reported that far more of their students were impacted than did teachers in low-poverty and low-and-mixed-poverty schools, even though their typical class sizes did not differ significantly (see Figure 1).

In addition to asking teachers to report on the number of their students dealing with community stressors, we also asked them to report on how frequently these stressors impacted learning time in their classes. While teachers in all schools acknowledged that these stressors have impacted learning time by making it difficult for some students to focus in class or causing students to miss class, the impact in high-poverty schools was much greater.

Teachers reported that the stressors impacted learning time in high-poverty schools’ classrooms three times as often as in low-poverty schools’ classrooms. On any given day, there is a 39 percent chance that at least one of these stressors affected learning time in a high-poverty school classroom, compared with a 13 percent chance in a low-poverty school classroom.

Our survey revealed more factors in addition to community stressors that cause high-poverty schools to lose greater amounts of instructional time than more-affluent schools. Over the course of the school year, high-poverty schools experience more disruptions due to a variety of institutional factors, including teacher absences, emergency lockdowns, and preparation for standardized tests, than low-poverty schools. And on a daily basis, these schools face more time loss from factors ranging from incorporating new students into classes to phone calls from the main office. This time loss adds up. Students in high-poverty schools lose roughly two weeks more learning time over the course of the school year and about thirty minutes more per day than students in low poverty schools.

In essence, California students in high-poverty schools are not able to access as much instructional time as the majority of their peers as a result of these challenges, creating a situation that threatens the very building blocks of educational opportunity.

Our broader study, of which this teacher survey is only one part, highlights the need for renewed attention to questions about learning time and equal educational opportunity. Because school days and minutes are distributed roughly equally across public schools, many have ignored time as a policy variable with implications for equity. The Keeping Time survey results remind us that allocated time is not the same as time available for learning. It points to the ways that economic and social stressors undermine the amount of available time schools can provide. For all California students to succeed, policymakers and educators will need to think about time in new ways. It is crucially important to recognize, grapple with, and redress inequalities in available learning time across public schools.

1. The report on our survey is available at idea.gseis.ucla.edu/projects/its-about-time. A video of a webinar on the research is available at https://vimeo.com/112202578.

2. For the purposes of our study, “high-poverty schools” are schools in which 75–100 percent of students are eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunch, “low-poverty schools” are schools in which 0–25 percent of students are eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunch, and “low-and- mixed-poverty schools” are schools in which 0–50 percent of students are eligible to received free or reduced-price lunch.