Language as the Lever for Elementary-Level English Language Learners

Bilingual education should be seen not as a remedial program for immigrant students, but as an enrichment program to help all students, including native English speakers, to be competitive in a global marketplace.

Improving the education of a growing sector of our school population – English language learners (ELLs) – is a pressing unmet need in our nation’s current public education system (Gándara 1994; Genesee et al. 2006; Hood 2003). Another urgent educational need is to prepare students to live and work in an increasingly globally connected world. Our students should be able to engage in cultural exchanges across the earth, but schools in the United States are not keeping pace with this need (Suárez- Orozco & Sattin 2007).

Bilingual education can help meet both these needs. In this article, I will explain why ELLs should be viewed as an asset rather than a burden and describe how we do this through two-way bilingual education at my elementary school, the International Charter School in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

Obstacles to ELLs' achievement in traditional schools

Researchers cite many reasons that ELLs do not thrive in a traditional environment.

- A common reaction to less-than-fluent English is for teachers to expect lower-level cognitive performance (Chamot & O’Malley 1989). Teachers of Latina/o ELLs may consider their students to be slow learners (Moll 1988) and simplify or water down the curriculum (Gersten & Woodward 1994; Moll et al. 1980; Ramirez 1992). Studies have shown that the result of such pedagogy is a low level of student engagement (Arreaga-Mayer & Perdomo-Rivera 1996; Ruiz 1995), which ultimately leads to what Valdés (2001) terms educational dead ends.

- In the current era of education reform, there is an increased focus on student performance on standardized tests administered only in English and narrowly focused on math and reading. Although the stated intent of the 2001 federal legislation No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was to eliminate gaps between subgroups of students – including between native and nonnative speakers of English – many argue that NCLB has hurt ELLs (e.g., Gándara & Baca 2008). NCLB places strong emphasis on testing in English, so ELLs are denied opportunities to use their native language, thus limiting their learning to basic skills with an impoverished curriculum (Gutiérrez 2001). We see this watered-down teaching in literacy practices in which teachers emphasize the acquisition of decontextualized skills such as vocabulary, decoding, and phonics instead of making these skills a part of a larger menu of meaningful activities in a literacy program.

- The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) were created without consideration of second-language acquisition research and do not take into account language development. Educators of ELLs are being asked to have their students achieve at higher levels with little support, as this passage from the introduction to the CCSS reveals:1

It is beyond the scope of the Standards to define the full range of supports appropriate for English language learners and for students with special needs. At the same time, all students must have the opportunity to learn and meet the high standards if they are to access the knowledge and skills necessary in their post–high school lives. Each grade will include students who are still acquiring English. For those students, it is possible to meet the standards in reading, writing, and listening without displaying nativelike control of conventions and vocabulary.

Dual-language programs: All students benefit

Developing language skills and providing access to academic content for ELLs is challenging without native-language support. Students learn best in bilingual programs in which they have nativelanguage support while learning a second language. But some bilingual programs have a benefit for non-ELLs, too. When native speakers of English are paired with native speakers of another language with the goal of both sets of students becoming bilingual, all students are learning to become global citizens. A speaker of a language other than English should be seen not as a problem but as part of the solution. We need to change the mindset from one in which bilingual education is seen as a remedial program for immigrant students to one in which it is seen as an enrichment program to help all students to be competitive in a global marketplace.

In dual-language bilingual education programs, students are taught in English and in a partner language with the goals of helping them to develop high levels of language proficiency and literacy in both languages of instruction; demonstrate high levels of academic achievement; and develop an appreciation for and an understanding of diverse cultures. Two-way immersion (TWI) is a form of dual-language education in which equal numbers of native English speakers and native speakers of the partner language are integrated for instruction so that both groups of students serve alternately in the role of language model and language learner.

The structure of TWI programs varies, but they all provide at least 50 percent of instruction in the partner language at all grade levels, beginning in pre-K, kindergarten, or first grade and running at least five years, though preferably through grade 12 (Hamayan, Genesee & Cloud 2013). TWI is an ideal educational response not only to the needs of ELLs but also to the need for global citizens because, in addition to academic achievement, bilingualism/biliteracyand cross-cultural awareness are goals of TWI programs (Howard, Sugarman & Christian 2003). It is a myth that students in bilingual programs do not learn English. Studies have shown that students in well-designed bilingual programs acquire academic English as well as and often better than children in all-English programs (Krashen 2005). Furthermore, they become proficient in two languages.

The structure of TWI programs varies, but they all provide at least 50 percent of instruction in the partner language at all grade levels, beginning in pre-K, kindergarten, or first grade and running at least five years, though preferably through grade 12 (Hamayan, Genesee & Cloud 2013). TWI is an ideal educational response not only to the needs of ELLs but also to the need for global citizens because, in addition to academic achievement, bilingualism/biliteracyand cross-cultural awareness are goals of TWI programs (Howard, Sugarman & Christian 2003). It is a myth that students in bilingual programs do not learn English. Studies have shown that students in well-designed bilingual programs acquire academic English as well as and often better than children in all-English programs (Krashen 2005). Furthermore, they become proficient in two languages.

Students need to become cognitively and behaviorally engaged with the world. To be able to help students develop the skills, sensibilities, and competencies needed to identify, analyze, and solve problems from multiple perspectives, schools must provide opportunities for students to become curious, learn to tolerate ambiguity, and synthesize knowledge within and across disciplines. Today’s youth need to be able to learn with and from their diverse peers, work collaboratively, and communicate effectively in groups. They will need to be culturally sophisticated enough to empathize with peers of different ethnic backgrounds and religions and of different linguistic and social origins. Duallanguage learning facilitates the acquisition of such skills.

The International Charter School

The International Charter School (ICS) is a dual-language public school of choice, offering linguistically and culturally responsive education to Rhode Island children and families.2 ICS has two language strands: Portuguese-English and Spanish-English. Approximately 50 percent of ICS students are dominant in a language other than English, 60 percent qualify for free or reduced-priced meals, and 50 percent are Latino.

Academic benefits for both ELLs and Non-ELLs

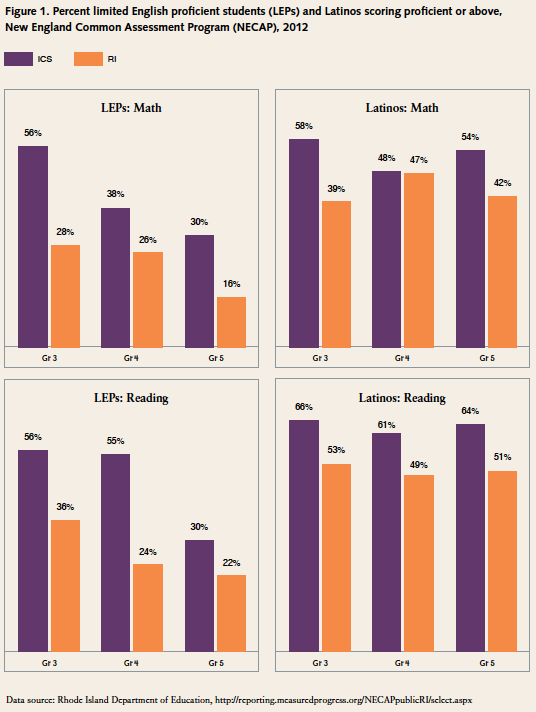

By having access to high-level academic content in their native language, ELLs are able to access the core curriculum and engage in higher-order thinking. Nationally, ELLs and Latinos experience failure at a higher rate than other groups of students (NAEP 2011). In Rhode Island, Latinos score lowest or near last on national comparative assessments (NAEP 2011). Research supports well-implemented dual-language education as the best model for ELLs(Krashen 2005), and ICS is proof. ICS’s Latinos and ELLs outperform their peers throughout the state (see Figure 1). And for native speakers of English, the ELL students are able to provide a native-language model that helps them learn the second language.

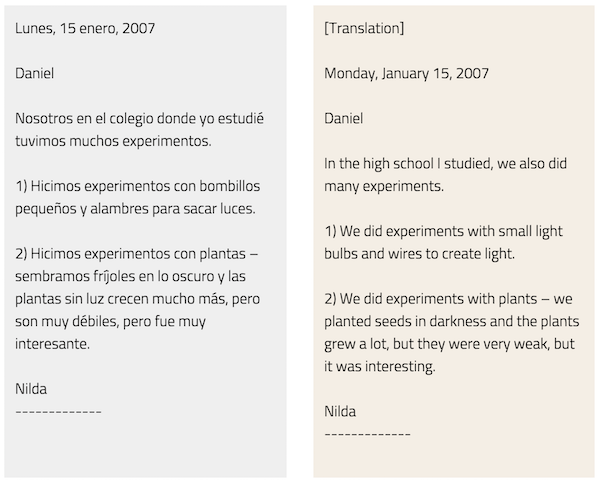

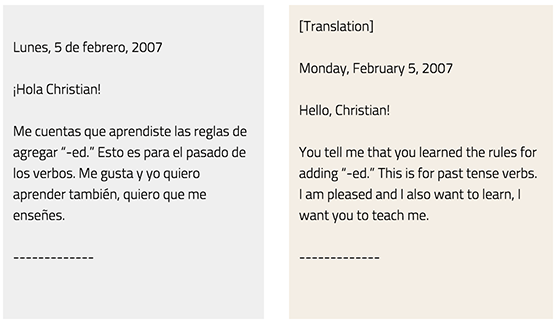

The dual-language model also allows parents to engage with their children’s learning and reinforce it at home. Parents are able to communicate with teachers in their native language. They are also able to engage with their children in their schoolwork. At ICS, we use a tool called “family message journals” (Wollman-Bonilla 2000), in which children and family members exchange letters regularly. Through these letters, families can keep up with what their children are learning in school and can witness the development of their writing. Parents can write in their native language, allowing them to participate fully and also to share their own childhood educational experiences. In contrast, in traditional schools, immigrant parents are often alienated because their experiences differ from those of the mainstream and are not valued.

For example, in the following letter, a mother responds to her son’s letter, in which he describes a science experiment he did in school, by telling him about experiments that she did as a student in Colombia.

These letters also allow the parents to learn from their children. In another letter, a father responds to his son, who had written to him about a lesson on “-ed” endings in English.

Cross-Cultural Competence

Teaching our students cross-cultural competence is more necessary today than ever. However, increased globalization is coming at a time when the pressure for education to focus on reading and math as assessed by standardized assessments is making the learning goals related to language and culture less and less of a priority.

At ICS, teaching cross-cultural competence is achieved both informally and formally. Learning with peers who come from different linguistic and racial/ethnic backgrounds and countries of origin removes the barriers to integrating with those from differing backgrounds. Parents of native- English-speaking students have reported that although their children struggled at times learning academic content 50 percent of the time in Spanish, the empathy that their children gained for what it takes to learn another language and to be part of another culture was invaluable and something that could be learned only in a dual-language setting.

Cross-cultural competence is also formally included in the curriculum. Our social studies curriculum, which was developed by ICS teachers and administrators, prepares learners to meet national and local social studies standards as they explore and document the school’s unique community of students and families. The resulting ICS social studies curriculum is structured around ten thematic strands, as defined by the National Council for Social Studies (Golston 2010). Two of the NCSS themes that are particularly relevant to teaching students to be culturally competent are the following:

- Culture: “A people’s systems of beliefs, knowledge, values, and traditions and how they change over time”; and

- Global connections: “Globalization has intensified and accelerated the changes faced at the local, national, and international level, and its effects are evident in the rapidly changing social, economic, and political institutions and systems.”

The curriculum follows a typical sequence of moving from the self to the outside world, with kindergarten focusing on the concept of “me,” first grade on “family,” second on “neighborhood,” third on “community,” fourth on “state,” and fifth on “country.” This framework facilitates students’ development of cross-cultural competence by making their lives and those of their classmates central to their learning.

Cross-cultural competence: Student and teacher points of view

Although my new school will not teach us equally in two languages, I will still be bilingual, a skill that few people have. . . . Other schools are sure to be places of great learning. But ICS in particular has given us the foundation of respect for many cultures, beliefs, and languages. And for that I owe a great thanks to all who have made that possible.

– Tomás, at his fifth-grade graduation

Our social studies unit, Documenting Cultural Communities, is all about their own culture and I think it is all connected – social studies, language, and culture. Students learn about their own background, where they came from, where their parents came from, and why it is important. They are very proud of documenting their own cultures, of being Brazilian, being Portuguese, being Cape Verdean.

– Silvia Lima, second- and third-grade teacher, Portuguese side

At every grade level, the cultural diversity of ICS makes up much of the content of the curriculum. As ICS Spanish-side teacher and curriculum developer Rosa Devarona said,

When we talk about food, they bring in dishes special to their family. Instead of “In Mexico, people eat...,” ICS students share what their Mexican family eats. After all, Mexico is a very diverse country. Students love talking about themselves and sharing their families’ lives. They are learning and teaching each other. It’s much more meaningful.

The focus of learning in third grade is “Community.” The second unit for third grade, Documenting Cultural Communities, is designed to broaden the students’ perception of community from one defined by geographical and physical characteristics to one defined by cultural characteristics such as traditions, language, food, dress, and so forth. Having our students and their families be the content of our teaching is only possible by having the diverse student population that a dual-language program facilitates.

Language as the solution

In dual-language programs, all students are viewed as having assets – linguistic and cultural – that help them prepare to succeed and fully participate in the changing world. And, by providing access to learning for ELLs and their families in their native languages, they provide ELLs with high-level academic opportunities. In such a model, language is the solution, not the problem.

More information on the International Charter School.

1. See www.corestandards.org

2. School of choice refers to the system by which any student in Rhode Island can apply to attend ICS and vacancies are filled by lottery.

Arreaga-Mayer, C., and P. D. Perdomo-Rivera. 1996. “Ecobehavioral Analysis of Instruction for At-Risk Language-Minority Students,” Elementary School Journal 96:245–58.

Chamot, A. U., and J. M. O’Malley. 1989. “The Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach.” In When They Don’t All Speak English, edited by P. Rigg and V. Allen, pp. 108–125. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Gándara, P. 1994. “The Impact of the Educational Reform Movement on Limited English Proficient Students.” In Language and Learning: Educating Linguistically Diverse Students, edited by B. McLeod, pp. 45–70. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gándara, P., and G. Baca. 2008. “NCLB and California’s English Language Learners: The Perfect Storm,” Language Policy 7:201–216.

Genesee, F., K. Lindholm-Leary, W. Saunders, and D. Christian. 2006. Educating English Language Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gersten, R. M., and J. Woodward. 1994. “The Language Minority Student and Special Education: Issues, Themes, and Paradoxes,” Exceptional Children 60:310– 22.

Golston, S. 2010. The Revised NCSS Standards: Ideas for the Classroom Teacher. Silver Spring, MD: National Council for the Social Studies.

Gutiérrez, K. D. 2001. “What’s New in the English Language Arts: Challenging Policies and Practices, ‘y Que?’” Language Arts 78, no. 6:564–69.

Hamayan, E., F. Genesee, and N. Cloud. 2013. Dual Language Instruction A to Z: Practical Guide for Teachers and Administrators. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hood, L. 2003. Immigrant Students, Urban High Schools: The Challenge Continues. New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Howard, E., J. Sugarman, and D. Christian. 2003. Trends in Two-Way Immersion: A Review of the Research. Report 63. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Krashen, S. 2005. “The Acquisition of Academic English by Children in Two-Way Programs: What Does the Research Say?” In Review of Research and Practice, vol. 3, edited by V. Gonzales and J. Tinajero, pp. 3–19. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Moll, L. 1988. “Some Key Issues of Teaching Latino Students,” Language Arts 65:465–72.

Moll, L., E. Estrada, E. Díaz, and L. M. Lopes. 1980. “The Organization of Bilingual Lessons: Implications for Schooling,” Quarterly Newsletter of the Laboratory for Comparative Human Cognition 2, no. 3:53–58.

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.

Ramirez, J. D. 1992. “Longitudinal Study of Structured English Immersion Strategy, Early-Exit and Late-Exit Transitional Bilingual Education Program for Language-Minority Children (Executive Summary),” Bilingual Research Journal 16:1–62.

Ruiz, N. 1995. “The Social Construction of Ability and Disability: II. Optimal and At-Risk Lessons in a Bilingual Special Education Classroom,” Journal of Learning Disabilities 28:491–502.

Suárez-Orozco, M., and C. Sattin. 2007. “Wanted: Global Citizens,” Educational Leadership 64:58–62.

Valdés, G. 2001. Learning and Not Learning English. New York: Teachers College Press.

Wollman-Bonilla, J. 2000. Family Message Journals: Teaching Writing through Family Involvement. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.