High-ELL-Growth States: Expanding Funding Equity and Opportunity for English Language Learners

The growing numbers of English language learners across the country provide an opportunity for state policymakers and education leaders to invest in and reap the benefits of a well-educated, culturally competent workforce.

An essential component of the “American dream,” the U.S. public education system carries the considerable responsibility of preparing a richly diverse student population for academic proficiency, economic mobility, and life success. Given the dynamic and evolving nature of the nation’s racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity, it should not be surprising that many American schoolchildren speak a language other than English at home. Nearly one in every ten public school students (roughly 4.5 million of 50 million total students) were classified as English language learners (ELLs) during the 2010-2011 school year (USDOE 2013a.)

While states such as California, Texas, Florida, and New York benefit from the experience of serving large numbers of ELL students, a growing number of states are only more recently considering and learning what it means to serve this unique population of students adequately and equitably. For many states, this learning has occurred in the face of judicial battles. In fact, every state except five1 has had at least one finance equity lawsuit filed against it (National Access Network 2010). Confronted with explosive increases in ELL enrollment and diminishing state budgets, the funding of ELL education at the state level presents a serious education policy challenge that requires immediate action, given its implications for educational equity and opportunity. For example, Nevada’s growing yet underfunded ELL population has attracted the attention of both the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund and the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada, which are considering suing the state for its violation of equal educational opportunities for marginalized students, including the lack of financial resources available specifically for ELL students (Doughman 2013). Although each state is different, insufficient human capital and funding capacity at the state level, coupled with the lack of a clear vision for ELL education nationally, creates huge challenges for schools and districts seeking to improve learning opportunities and outcomes for their ELL students.

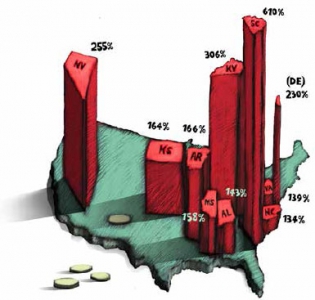

In this article, we review state-level ELL funding for the ten states experiencing the highest ELL population growth between 2000-2001 and 2010-2011. These high-ELL-growth states are South Carolina, Kentucky, Nevada, Delaware, Arkansas, Kansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, and North Carolina. While the U.S. ELL population has grown 18 percent from 2000-2001 to 2011-2012, which is a significant increase, these states have experienced ELL growth ranging from 135 percent in North Carolina to an astonishing 610 percent in South Carolina. These dramatic figures underscore not only the massive extent of this demographic reality but also the great opportunity such cultural and linguistic diversity represents for states eager to invest in and reap the benefits of a well-educated, culturally competent workforce.

In this article, we review state-level ELL funding for the ten states experiencing the highest ELL population growth between 2000-2001 and 2010-2011. These high-ELL-growth states are South Carolina, Kentucky, Nevada, Delaware, Arkansas, Kansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, and North Carolina. While the U.S. ELL population has grown 18 percent from 2000-2001 to 2011-2012, which is a significant increase, these states have experienced ELL growth ranging from 135 percent in North Carolina to an astonishing 610 percent in South Carolina. These dramatic figures underscore not only the massive extent of this demographic reality but also the great opportunity such cultural and linguistic diversity represents for states eager to invest in and reap the benefits of a well-educated, culturally competent workforce.

Money matters, but how much is enough, and where should it go?

In many ways, our recent work in Nevada serves as a useful starting point for examining both the complexity and the opportunity associated with funding ELL education at the state level. As co-authors of the report Nevada’s English Language Learners: A Review of Enrollment, Outcomes, and Opportunities, we were struck by the dramatic variation in how states calculate, define, fund, and otherwise support ELL education (Horsford, Mokhtar & Sampson 2013). To some degree, these differences are understandable, given the great diversity within ELL populations in and across states. At the same time, such variation makes it extremely difficult to establish a clear sense of what works and, in the case of ELL funding, how much money is enough. The evidence is limited.

Since 1990, there have been only four costing-out studies conducted in the United States that focused exclusively on ELLs (see Arizona Department of Education 2001; Gándara & Rumberger 2008; New York Immigration Coalition 2008; National Conference of State Legislatures 2005). And because each state’s needs, educational infrastructure, and funding mechanisms are so drastically different, determining how and where ELL funds should be allocated is difficult. Although most studies have concluded that ELL-specific services remain woefully underfunded, the amount of dollars to be allocated and where they should be spent remains less clear. Yet this information is precisely what policymakers want to have in order to decide whether or not money used to fund ELL education will result in a return on state investment.

This underfunding was certainly the case in Nevada. Policymakers have finally acknowledged the need to fund ELL education at the state level in Nevada, a Mountain West state outpacing the rest of the nation in population growth, immigration, and increasing ethnic and linguistic diversity. Although the level of funding is still being debated, what has been shown is the pivotal role states can play in expanding equity and opportunity for what will continue to be a growing share of American public school students. Although our research to date has been exploratory and it is much too early to infer any direct relationships between state-level ELL policy and funding and student-level outcomes, efforts to compare Nevada with other high-ELL-growth states have further revealed the disparate nature and fragmentation of ELL policy and funding at the state level.

ELL enrollment and funding in high-ELL growth states

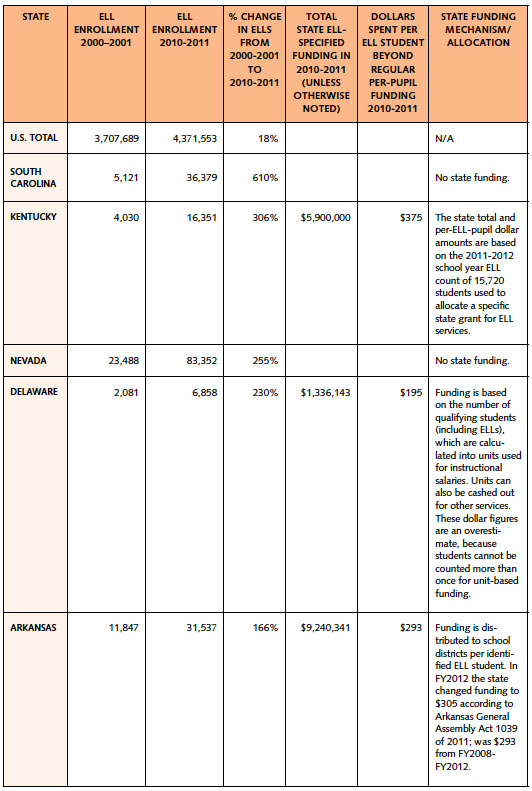

When it comes to funding ELL education, states that elect to fund ELL-specific services do so in different ways and at varying levels, including block grants, additional per-pupil dollars, weighted formulas, or unit or general “lump sums” (Horsford, Mokhtar & Sampson 2013). To illustrate this point, Figure 1 describes ELL enrollment, growth, funding, and allocation in the top ten fastest growing ELL states (respectively): South Carolina, Kentucky, Nevada, Delaware, Arkansas, Kansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, and North Carolina.

Although these ten states vary widely in their ELL enrollment, they have experienced extreme growth in their ELL populations in just one decade. Collectively, they reflect the great variation in how states approach ELL education.

Dollars spent per ELL student beyond a state’s regular per-pupil funding expenditure level varied greatly based on both funding mechanism and level. In order to provide some comparison of how states funded educational opportunities for their ELL students, we collected per-ELL-pupil funding figures as reported directly by states, as well as calculated figures for nonreporting states by identifying that state’s total budget for ELL-related services and resources and dividing that figure by the state’s ELL enrollment count for the corresponding year as reported by NCES. Some states base their budgets on specialized formulas, which we used to arrive at an estimated average per-ELL-pupil figure (see Figure 1, sixth column). Although these figures reflect publicly available budgets and data for ELL students, it is difficult to compare state ELL funding levels due to the variations in how states collect and report ELL data (with figures that are also different from what are reported in national databases), and due to variation in approaches used to fund ELL education. This exercise in coming up with comparable ELL spending figures reiterates the need for more transparency and equity in funding ELL education.

Figure 1. ELL Enrollment, Growth, and Funding in the Top 10 Fastest Growing ELL States from 2000 to 2010.

Notes: Dollar figures are rounded to the nearest dollar. Ohio was not included due to inconsistent figures. California, North Dakota, and Tennessee did not report ELL numbers to NCES for one or both years.

Sources: U.S. Department of Education, NCES 2012; USDOE 2013, n.d.; Verstegen 2011; Kentucky Department of Education 2012; State of Delaware 2012; Arkansas Department of Education 2013; Kansas State Department of Education 2008; Alabama Legislative Fiscal Office 2012; Virginia Department of Education 2012; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction 2011.

Of the states highlighted in Figure 1, South Carolina reflects the largest share of ELL population growth between the 2000-2001 and 2010-2011 school years at 610 percent. Ironically, however, like Mississippi and Nevada, South Carolina does not provide any state dollars to fund ELL education. In contrast, North Carolina and Virginia, which have each seen their ELL populations more than triple over the last decade, provide $741 and $401, respectively, per ELL student. And as noted in Figure 1, some states do not fund ELL education at all, relying mainly on federal funding that averaged $180 per ELL pupil in 2010-2011 (USDOE n.d.). Despite being a high- ELL-growth state and having the highest density of ELL students of any state in the country, Nevada counts itself among those states that do not fund ELL education, further illustrating the severe inability of the state to meet the evident needs of nearly one-third of its overall student population.

Funding educational opportunity and equity

Sadly, the fact that states have focused for more than thirty years on standards and accountability absent the resources and investments needed to achieve those standards and to sustain success reflects a major flaw in state-level education policy. The result is a system adept at labeling failure but incapable of doing anything about it. As noted in our comparison of high-ELL-growth states, funding levels, mechanisms, and allocations vary widely, making it difficult to determine who gets what and whether or not funding translates into improved student achievement. Perhaps most important is the fact that a much-needed focus on equity in education policy, and particularly on state funding equity (USDOE 2013b; Baker, Sciarra & Farrie 2012), reflects the pendulum swinging back to what the Elementary and Secondary Education Act originally intended – the provision of increased federal resources for underserved schools and students and an emphasis on access to equal education.

In Gándara and Rumberger’s (2007) costing-out study of linguistic minorities in California, the researchers utilized a definition of adequacy that they described as reclassification and maintenance of academic proficiency, which moves students from ELL to Fluent English Proficiency status while providing resources until all students receiving support become proficient in other academic content. The schools in their pilot study were included based on high levels of ELL academic achievement, location, and curriculum. The study identified five areas that require investment for ELL success:

- A high-quality preschool program;

- A comprehensive instructional program that addresses both English language development and the core curriculum;

- Sufficient and appropriate student and family support;

- Ongoing professional support for teachers with a significant focus on the teaching of ELL students; and

- A safe, welcoming school climate.

Although these recommendations are not very specific, they do offer insight into how states can approach an ELL costing-out study that defines adequacy in ways that go beyond test score data and how they can target investments in areas that go beyond staffing. Any costing-out analysis must also recognize the diversity among the ELL student population, as their needs vary based on their “linguistic, social, and academic backgrounds and the age at which they enter the U.S. school system” (Gándara & Rumberger 2006, p. 3). Studies to develop funding formulas should include the opinions of ELL experts, leaders from schools or districts with high-performing ELL populations, highlights of ELL best practices, and ELL-specific indicators of engagement and outcomes (Jimenez- Castellanos & Topper 2012).

Conclusion

State policymakers and education leaders should not regard such demographic and educational trends as a challenge or a problem to be solved but rather as an opportunity to modernize their states’ approaches to educating our nation’s diversifying student population. Funding ELL education is not merely another expense but rather a human capital investment essential to the development of successful citizens and thriving state economies.

At the national level, we agree with the U.S. Commission on Educational Excellence’s observation that “In an increasingly global economy, these young people could be our strategic advantage” (USDOE 2013b, p. 13). Seizing this opportunity requires more research on the best ways to educate each and every English language learner – not only for the sake of students who speak another language but also for that of the nation’s equity and excellence agenda overall. It is critical that state and federal education policies stay ahead of this trend, and to do so requires close attention and immediate action at the district, state, and federal levels if these students are to receive the equitable, high-quality education they deserve.

1. Delaware, Hawaii, Mississippi, Utah, and Nevada.

Alabama Legislative Fiscal Office. 2012. Education Trust Fund Comparison Sheet: FY2012 Enacted.

Arizona Department of Education. 2001. English Acquisition Program Cost Study: Phases I through IV. Phoenix, AZ: Arizona Department of Education.

Arkansas Department of Education. 2013. How Are School Districts in Arkansas Funded?

Baker, B., D. Sciarra and D. Farrie. 2012. Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card. Newark, NJ: Education Law Center, Rutgers Graduate School of Education.

Doughman, A. 2013. “Education Advocates Threaten Lawsuit over Funding Public Schools.” Las Vegas Sun (May 1).

Gándara, P., and R. Rumberger. 2006. Resource Needs for California English Learners. University of California, Linguistic Minority Research Institute.

Gándara, P., and R. Rumberger. 2007. Resource Needs for California English Learners: Getting Down to Facts Project Summary. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Institute for Research on Education Policy and Practice.

Gándara, P., and R. Rumberger. 2008. “Defining an Adequate Education for English Learners.” Education Finance and Policy 3:130–48.

Horsford, S. D., C. Mokhtar and C. Sampson. 2013. Nevada’s English Language Learners: A Review of Enrollment, Outcomes, and Opportunities. Las Vegas: University of Nevada Las Vegas, Lincy Institute.

Jimenez-Castellanos, O., and A. M. Topper. 2012. “The Cost of Providing an Adequate Education to English Language Learners: A Review of the Literature.” Review of Educational Research 82, no. 2:179–232. DOI: 10.3102/0034654312449872

Kansas State Department of Education. 2008. English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) and Bilingual Education in Kansas.

Kentucky Department of Education. 2012. Kentucky Education Facts.

Migration Policy Institute. 2010. ELL Information Center Fact Sheet Series. No. 1.

National Access Network. 2010. Litigations Challenging Constitutionality of K–12 Funding in the 50 States. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

National Conference of State Legislatures. 2005. Arizona English Language Learner Cost Study. Prepared for the Arizona Legislative Council.

New York Immigration Coalition. 2008. Getting It Right: Ensuring a Quality Education for English Language Learners in New York. New York: New York Immigration Coalition.

North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. 2011. Information Analysis, Division of School Business: Highlights of the North Carolina Public School Budget.

State of Delaware. 2012. Budget Archive: FY2011.

U.S. Department of Education. 2013a. ED Facts/Consolidated State Performance Reports, 2010-11.

U.S. Department of Education. 2013b. For Each and Every Child: A Strategy for Education Equity and Excellence.

U.S. Department of Education. n.d. ED Data Express: Data about Elementary & Secondary Schools in the U.S.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2012. Condition of Education, Table A-8-1, pp. 152–155.

Verstegen, D. A. 2011. A Quick Glance at School Finance: A 50 State Survey of School Finance Policies. University of Nevada, Reno

Virginia Department of Education. 2012. School Finance: Overview of Standards of Quality Funding Process,