Expanding Transition: Redefining School Readiness in Response to Toxic Stress

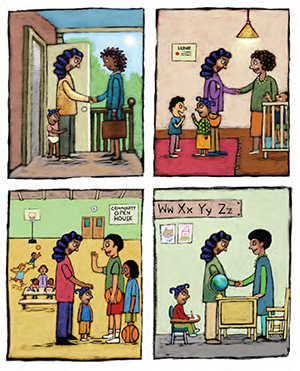

Early childhood interventions such as home-visiting and kindergarten preparation programs can mitigate the effects of toxic stress and equip children with the skills and support they need for a successful transition into school.

Travis walked into my third grade classroom in Washington, D.C., not knowing how to read, do basic addition or subtraction, or even write his last name. It was March of 2001, and I was his third teacher that school year. Travis, his mother, and his siblings were chronically homeless, moving from one shelter or housing project to the next. As his teacher, I simply did not know where to start with Travis academically. How could I ask him to read  the novel Because of Winn Dixie, when he had never been taught all the letters in the alphabet? How could I expect him to know multiplication, when he had never had the opportunity to learn addition?

the novel Because of Winn Dixie, when he had never been taught all the letters in the alphabet? How could I expect him to know multiplication, when he had never had the opportunity to learn addition?

A few months after Travis joined my classroom, I walked him home from school. I don’t remember now why I walked him home, but I remember I wanted to speak to his mother and I had been unable to reach her. Travis lived about five blocks from school, and as we arrived at his apartment, he hesitated. His sisters had gone ahead of us and run into the backyard. It was then that Travis told me that he, his mother, and his two sisters were living in their car, which was parked in the backyard of the apartment building. No one was in the car that afternoon, so I took the children back to school and with school administrators called the D.C. Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA). That night at the school, Travis’ mother gave Travis and his siblings up to CFSA. She stood before us sobbing and told us over and over about how she simply could not keep them – she did not have the support or resources to provide the life she wanted for them. While I wanted Travis to learn the alphabet, he and his family were focused on basic needs and survival. What I realize now is that long before he entered my classroom, Travis had not been successfully prepared for school on multiple levels.

Transition is typically defined as the time in which we move children from pre-K into the K–12 education system. Put more concretely, transition is often about K–12 school readiness. One aspect of school readiness is to prepare children academically for kindergarten, but it should also include meeting a child’s basic needs from a very early age. When these basic needs – food, shelter, clothing, and safety – are met, a child can develop healthy social, emotional, and cognitive skills that are also essential to school readiness, allowing children to be prepared to acquire the academic skills.

Early childhood interventions, including home-visiting and kindergarten prep programs, can equip children like Travis with both the academic skills and the basic needs that set children up for a successful transition into school. The cost of not preparing children in both ways is too high. We know that a child like Travis – who cannot read proficiently by the end of third grade and who lives in poverty – is thirteen times less likely to graduate on time or even graduate at all compared to his proficiently reading peers. We also know that not graduating from high school and living in poverty puts a person at great risk for worse life outcomes than their peers who do graduate (Fiester 2010). We must think more broadly about transition and take a multifaceted and comprehensive approach to school readiness.

TOXIC STRESS AND ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES

As a young educator, I did not understand that Travis was dealing with profound toxic stress. Toxic stress is generally defined as “strong, frequent, and/or prolonged activation of the body’s stress-response systems in the absence of the buffering protection of adult support” (Shonkoff, Boyce & McEwen 2009). Chronic homelessness, mental illness, substance abuse, neglect, interpersonal violence, and economic insecurity are all examples of the kind of traumatic, adverse experiences that produce toxic stress (Center on the Developing Child 2012). The impact of these experiences on children has profound, far-reaching effects on healthy development. In fact, developmental research reveals that in the context of toxically stressful environments, children cannot develop healthy neural connections that are vital for learning (Klebanov & Travis 2015).

Given this data, our approach to early education transitions for children who experience toxic stress must be different from that of their peers who do not. It demands that interventions that mitigate toxic stress happen as early as possible in those children’s lives, so that any barriers to school readiness are removed long before they get to kindergarten. Fortunately, there are effective interventions that can do just that.

HOME VISITS AS INTERVENTIONS THAT MITIGATE TOXIC STRESS

I previously directed two early childhood home-visiting programs at Meeting Street in Providence, Rhode Island – Early Head Start (EHS) and Healthy Families America (HFA) – both of which serve families living in poverty. Both programs work with families to build a solid foundation for their children so that they are set up for success in school and life.

EHS, a part of the larger national Head Start program, is run by the federal Administration for Children and Families. It was born out of the civil rights movement fifty years ago with the goal to close the enormous gap between children who live in poverty and their peers who do not. Its main focus areas are promoting school readiness and providing families with wraparound social service support to remove barriers that might negatively impact a child‘s transition into school.

HFA is a program run by Prevent Child Abuse America. It is an evidence-based child-abuse prevention program for low-income families. HFA uses a trauma-informed approach to working with families that focuses on supporting healthy bonding and attachment between parents and children. This healthy bonding and attachment in turn supports healthy brain development. As with EHS, HFA also focuses on wraparound social service support and school readiness.

These programs allow their staff members the privilege of working with families in their home environments. When a home visitor walks into a family’s home, she gets to experience their strengths and challenges in an authentic and intimate way. The opportunity to clearly observe what each child and family may need to help them thrive is an enormous advantage to our work. The home context allows us to clearly see the toxic stressors and barriers to healthy development that exist for each child and family as well as the strengths that each family possesses. As a result, home visitors are well positioned to help families access the social service support they may need and can more easily build on the strengths of the family.

Working with families in their home setting allows staff to uncover their needs and strengths and provide support and encouragement in whatever way necessary. Many of the families we worked with lived in homes with extended, intergenerational family members; home visitors worked on building on that strength and including the whole family in the program. For families facing eviction, home visitors were able to help them know their rights as tenants and work toward a plan to help them stay in their home. A majority of our families struggled with mental health issues, and we provided them with mental health consultation as well as referrals to ongoing counseling services. Several women we worked with were in relationships where they experienced intimate partner violence; home visitors worked to create safety plans, and in many cases worked to get them into domestic violence shelters or other resources. For one teen mother who dropped out of high school, her home visitor helped her get into a GED program and supported her through staying on track. By providing needed supports, these programs help families deal with toxic stressors that can impede their ability to give their child what they need for healthy development. This is the work of transition; it is at the core of whether or not a child is set up to succeed in school.

Research shows that these interventions succeed on several levels. A national evaluation of EHS found that:

Three-year-old Early Head Start children performed significantly better on a range of measures of cognitive, language, and social-emotional development than a randomly assigned control group. In addition, their parents scored significantly higher than control group parents on many aspects of the home environment and parenting behavior. Furthermore, Early Head Start programs had impacts on parents’ progress toward self-sufficiency. (Administration for Children and Families 2006)

According to an HFA impact brief, children who participated in HFA were more likely to be in gifted programs and less likely to receive special education services or repeat first grade than their peers who did not take part in HFA; these participants also exhibited positive learning behaviors such as following oral directions and playing cooperatively upon entering school (Healthy Families America n.d.). This data give strong support to the argument that children must have early access to preventative programs like EHS and HFA in order to transition successfully into school.

Findings on Olneyville's Home-visiting Programs from Brown's Urban Education Policy Program

Adapted with permission from Lovitz, M., C. Ross, and M. Costa, “Navigating the Many Dimensions of School Readiness: Supporting Parents, Families, and Children through Early Childhood and the Transition into School,” Unpublished research report, Urban Education Policy graduate program, Brown University, 2015.

Connecting to Resources

In interviews and focus groups with HFA and EHS staff and parents, connecting families to community resources was seen as a critical component of the family support workers’ job. For example, parents were connected through the home visiting program to formal educational pathways like GED programs or CNA courses. During a home visit observed by two research team members, the family support worker provided the mother with many different resources such as a budgeting sheet, information about savings programs, and information about GED programs. These resources were provided based on previous interactions and requests for services, showing how easily the transfer of knowledge about resources can be facilitated within a trusting relationship.

Other examples of connections to resources mentioned by parents and staff members include mental health services, financial assistance, childcare, and diapers or formula for babies. One EHS parent said:

My home visitor helps me a lot with any resources I could need. . . . Anything I need for [my child], like if I’m lacking on anything I could possibly need, I could just tell her. She’s helped me with food banks, furniture, anything, which I didn’t think she would possibly know about, but she does.

Parent Education

Focus groups and interviews with staff and parents also highlighted the program’s goal of helping parents to increase their knowledge of child development. In a focus group, one home visitor explained the parent education component in this way:

It’s not so much teaching them how to be parents but reinforcing a lot of things that they’re already doing and hopefully them learning things along the way.

Another staff member explained that in helping parents understand their role in their child’s school readiness, they

stress the fact that they are their child’s first teacher; their child is not going to go to school to learn everything. Parents are going to lay that foundation at home.

A parent shared that through EHS she learned that she should be speaking out loud to her children and reading books to them to prepare them for school. She explained that her two youngest children benefited from this knowledge and are ready to learn in ways that her oldest child, whom she had before she learned these techniques, was not.

Home visiting was an opportunity for parents to learn about activities that promote development and why they work. For example, the home visitor we observed demonstrated how exploratory play (e.g., building a fort or going outside) provided the opportunity for language exposure and connected games to specific cognitive skills (e.g., sorting, categorizing, comparing, organizing, matching, recognizing shapes). Staff see an important part of their role as making sure parents know about developmentally appropriate behaviors and feel equipped to notice possible delays. One staff member noted:

Helping parents to detect delays or potential delays and then providing activities to assist or referrals out to early intervention, . . . ongoing assessment around the child’s development and also their social-emotional development . . . supports the child in continued growth.

Parents’ gaining an understanding of developmental language itself is also an asset. One EHS staff member explained that

just being able to talk and use the language of learning and child development when you are interacting with a teacher or a school official or the school department – I think is a real advantage for families.

CREATING A PATH OF COMPREHENSIVE SERVICES TO SUPPORT EARLY EDUCATION TRANSITIONS

President Obama’s 2013 plan to improve access to high-quality early childhood education has brought a renewed focus and increased funding opportunities to the field, which opens up opportunities for the education world to think about transition into K–12 differently than it has in the past. Initiatives that help connect early preventative services to high-quality kindergarten preparation programs build on the vision set out by President Obama.

The development of programs that create a path of educational and social service supports for children from as early as their prenatal development until their transition into kindergarten are exciting opportunities to provide a comprehensive approach to transition and school readiness. The supports families receive and skills they develop from the previously mentioned homevisiting programs are an integral part of successful transition into the primary grades and beyond. A complement to these home-visiting programs are kindergarten preparatory (K-prep) programs, which focus on the academic and behavioral skills needed for school readiness. (In the next section, I will discuss in greater detail the K-prep summer program that was a key part of Meeting Street’s Olneyville Education initiative, which I directed.)

Continuing services for children when they age out of the home-visiting programs in which they are enrolled is key. In Rhode Island, Early Head Start and Healthy Families America funding ends at ages three and four, respectively. At the end of each program, families should have the option to transition children into some kind of non-parental formal education setting such as Head Start, preschool, pre-K, or a licensed childcare program. However, space is limited in these programs and there is no guarantee that a child will transition successfully into one. In Rhode Island in 2014, Head Start served only 34 percent of the children who were income-eligible, and there was an 11 percent reduction in open preschool seats as well as a 4 percent reduction in the enrollment capacity of licensed childcare centers (Rhode Island KIDS COUNT 2015).

Children who age out of EHS and/or HFA and are not transitioned into a high-quality early childhood program are at significant risk of losing the gains made while in the programs. Toxic stress and poverty do not suddenly end at age three, four, or five. For families who age out of home visiting, it is imperative that services do not stop but that they have opportunities to transition into another high-quality early childcare program to mitigate toxic stress and sustain gains achieved through the home-visiting programs.

KINDERGARTEN PREP IN OLNEYVILLE

As one of the poorest neighborhoods in Providence, Olneyville is a prime place for this work mitigating the impact of toxic stress. According to the Providence Plan (2012), 37 percent of neighborhood residents live in poverty, and the median income is $31,000 per year. Residents also have a low level of educational attainment, with 43 percent of those age twenty-five or older without a high school diploma and only 13 percent earning a bachelor’s degree.

Olneyville has a high concentration of traditionally underserved populations. Community profile data collected by the Providence Plan (2012) indicates that the neighborhood is 59 percent Hispanic, 19 percent non-Hispanic White, 15 percent Black, and 4 percent Asian; 63 percent of residents age five and over speak Spanish at home.

In addition, Olneyville is well situated for this work because it is rich with assets that families can access. Olneyville houses the Scalibrini Center – a community center that has English classes, citizenship classes, and a WIC office – as well as the Boys and Girls Club, D’Abate Community Elementary School, the Olneyville Housing Collaborative, the Manton Avenue Project, and United Way. All of these entities support the healthy development of the neighborhood and can act as supports to the families and children enrolled in home-visiting programs.

The Olneyville Education K-prep program is an intensive, five-week program that – in summer 2015 – served fifty-two children in three classrooms, one of which was a Spanish bilingual classroom. The bilingual classroom was held at the Manton Avenue Housing Development – Section 8 housing where many of the families live – and the other two classes were held at the D’Abate Community School, a Providence public school that has deep roots in the Olneyville community.

The goal of this summer K-prep was to equip students with the academic and behavioral skills that will help them with their transition into kindergarten. The classrooms were purposefully small in size and staffed with a certified teacher and teaching assistant to ensure high-quality instruction and a low student-to-teacher ratio. The curriculum focused on basic academic skills including identification of numbers, letters, shapes, and colors, as well as students learning to write their own name. The curriculum also focused on the behavioral aspects of attending school such as following directions, cooperating with classmates, and following a structured routine.

A small number of students did attend Head Start or were enrolled in Early Head Start, but for most of the students, the K-prep program was their first experience in a classroom setting, having spent their first five years in informal or unlicensed childcare settings. The range of student’s skills upon entering the K-prep program varied, but many children had large gaps in basic academic skills: holding a pencil, identifying letters, knowing shapes and colors, and being able to write their name. Other children had some of these basic skills, but needed a lot of behavioral support. Teachers focused on differentiating their instruction for this range of skills. Over the course of the summer, the growth of the students was staggering. Every single child made gains in all areas as measured from the initial assessments to the end assessment.

One particular child had never been in a formal childcare setting before coming to our program, having been taken care of by family for all of his life. When he arrived, he could only identify a few letters, could not hold his pencil properly, or spell his name. He also struggled with typical school routines and cooperative learning settings. By the end of the program, he was able to identify many more letters, hold his pencil, and spell his name. He also made significant progress in learning how to successfully participate in a formal school setting. Another child, whose family was struggling with insecure housing, domestic violence, and extreme poverty also made progress in all areas that we assessed, including letter, color, and shape recognition as well as following typical school routines. There was still much work to do, but he was on a better path to kindergarten readiness.

While the results of this particular summer K-prep were exciting, the program only addressed the academic and behavioral aspects of school readiness; students did not receive the social service support that many needed and which could have helped them grow even more. The combination of a high-quality K-prep program – focused on the academic and behavioral side of school readiness – coupled with a home-visiting program that provides comprehensive social service support could give children intensive school readiness programs that would ensure a successful transition into kindergarten.

EARLY INTERVENTIONS TO FIGHT THE EFFECTS OF TOXIC STRESS

When children walk into their first day of school, their whole life story walks in with them. For children who enter the classroom door with the weight of toxic stress, they are already at much greater risk for worse outcomes in school and life than their peers who do not experience toxic stress. Preventative programs like EHS, HFA, and high-quality K-prep can mitigate the detrimental effects of toxic stress and put a child on the road to school readiness. While the opportunity is great to provide these preventative programs to all children who need them, it will take a commitment from the entire education system. As a field we must agree that comprehensive preventative programs are essential to school readiness and successful early education transition, and they must be provided to students who need them as early as possible.

Our education system failed Travis. For him, transition should have started very early in his life – long before he entered my classroom. His story, and those of so many children like him, must serve as a cautionary tale and propel the field to act. Working together, high-quality preventative programs can keep us from failing more children like Travis.

Administration for Children and Families. 2006. Early Head Start Benefits Children and Families: Research to Practice Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. 2012. The Science of Neglect: The Persistent Absence of Responsive Care Disrupts the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 12.

Fiester, L. 2010. Early Warning! Why Reading by the End of Third Grade Matters: A KIDS COUNT Special Report. Baltimore, MD: The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Healthy Families America. [n.d.] “HFA Impacts on Children,” Prevent Child Abuse America.

Klebanov, M. S., and A. D. Travis. 2015. The Critical Role of Parenting in Human Development. New York: Routledge

Providence Plan. 2012. “Rhode Island Community Profiles: Census Track 19.”

Rhode Island KIDS COUNT. 2015. Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook.

Shonkoff, J. P., W. T. Boyce, and B. S. McEwen. 2009. “Neuroscience, Molecular Biology, and the Childhood Roots of Health Disparities: Building a New Framework for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention,” Journal of the American Medical Association 301, vol. 21: 2252–9.