“Buy-In” vs. “Allowed In”: Lessons Learned in Family Engagement Program Recruitment and Retention

Parent focus groups reveal insights about the communication, collaboration, and community buy-in needed for successful family engagement in an under-resourced urban district.

All the lessons we’ve learned introducing a family engagement program in thirty “low-performing” Philadelphia elementary schools would easily fill this issue. You might expect us to detail the challenges of recruiting 3,000 low-income families to participate in an after-school program. You might expect us to lament “hard-to-reach” parents.  You might expect us to warn against working in a school district facing serious, ongoing financial crises. That’s not what you will find here. We have too many positive and valuable takeaways to share that we have learned in this rigorous work from our district partners and astute parents.

You might expect us to warn against working in a school district facing serious, ongoing financial crises. That’s not what you will find here. We have too many positive and valuable takeaways to share that we have learned in this rigorous work from our district partners and astute parents.

Here is what you will find: an honest discussion of our project’s family recruitment challenges, successes, and recommendations; the wise insights parents expressed during focus groups and implications for increasing families’ sense of welcome in schools; and an exhortation not to avoid but rather to advance into a district in crisis. What better place to invest time, resources, and energy than in underfunded schools? Where better to learn the lessons of collaboration than around a table littered with thrice-revised plans?

With support from a federal Investing in Innovation (i3) grant, our project team has been implementing the FAST (Families and Schools Together) program in thirty Philadelphia schools to improve family engagement and, by extension, advance school turnaround. Our team includes the nonprofit Families and Schools Together, Inc.; the Early Childhood Education Department within the School District of Philadelphia (SDP); and our local agency partner in Philadelphia, Turning Points for Children. The American Institutes for Research (AIR) is the independent evaluator.

At the Wisconsin Center for Education Research (WCER), we play an oversight and assistance role. One co-author of this article (Susan Smetzer-Anderson) has been supporting on-the-ground colleagues in strategizing recruitment, researching parent communication preferences, collaborating with AIR on focus groups, and compiling the project’s stories for dissemination. As the program manager, the other co-author (Jackie Roessler) has also managed two other research projects that involved implementing FAST in fifty-six schools. Weekly conference calls, site visits, and ongoing communication with our Philadelphia partners guide our work and, together, we bridge the project to education stakeholders and our funders at the U.S. Department of Education.

As of this writing, our i3 journey is eighteen months from the finish line.

CHALLENGES AND PROGRESS WITHIN THE FAST I3 PROJECT IN PHILADELPHIA

2012-2013

We receive a five-year, $15 million i3 grant to validate a targeted approach to reform that reduces critical barriers to school success, including lack of family engagement and family stress, in sixty low-performing elementary schools. The planning timeframe is reduced due to required funding timelines.

2013-2014

A severe budget crisis in Philadelphia leads to lay-offs of 3,783 SDP employees. Principals handle enrollment tasks and substitute as lunch monitors and classroom teachers – just as we launch FAST in thirty schools. Severe winter weather alters school schedules and changes FAST timelines. A school principal is indicted in a cheating scandal. We serve 545 families.

2014-2015

FAST continues in all thirty schools. Of thirty principals, nine are new and need to be brought up to speed. Our target audience is expanded to include kindergarten and first-grade families. The team copes with tragedy as its leader in Philadelphia is shot and killed while waiting at a bus stop. (A co-worker unrelated to the project is arrested.) The project moves forward. We serve 531 new families.

2015-2016

The next stage of FAST (FASTWORKS) is launched in all thirty schools for first- and second-grade families. To advance the district’s “Read by 4th” goals, the project team collaboratively creates a “Success in 2nd Grade” program and pilots it at twenty-nine schools. Teacher buy-in increases.

2016-2017

FASTWORKS continues, and the team plans to launch FAST in the thirty control schools. Eighteen principals will require introduction to the program that their predecessors agreed to implement. (Success in 2nd Grade program needs a new funding stream to continue.)

2012–2016

AIR conducts a randomized control trial that includes sixty elementary schools (thirty treatment, thirty control) and a quasi-experiment involving eight matched school pairs. The combined evaluation is assessing FAST impacts at the individual and school levels.

INCREASING FAMILY ENGAGEMENT THROUGH FAST

FAST is an evidence-based family engagement and prevention program created in 1988 by Dr. Lynn McDonald and developed through years of research at WCER. In the more than twenty-five years since it was first introduced, FAST has been implemented in forty-eight U.S. states and twenty countries, and the program has been recognized by the United Nations, the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.1 The eight-session program, designed for both students and their parents, is held in school classrooms and facilitated by trained teams that include at least one parent leader, a school partner (either a teacher or school counselor), and an agency partner. The two-hour sessions focus on strengthening parent-child communication, building social capital, increasing families’ comfort levels in schools, and improving children’s behavioral skills.

FAST sessions are designed to be fun, conceptually rich, developmentally appropriate, and engaging for both adults and children. The program is also culturally adaptable. A “special play” time gives parents one-on-one time with their children. Parents also have time to meet other families and discuss topics they choose, building a broader support network in the process. A shared, free meal brings families together around the same table – a rare experience for many of them. Something that surprises parents is that children serve their parents dinner; this not only reinforces the children’s sense of responsibility, but parents are gratified by the show of respect and see how their children can be helpful. In subtle ways, FAST draws adults and children closer together and at the same time reinforces parental authority.

In the thirty Philadelphia schools we first worked with in 2013, we invited only kindergarten students’ families to attend, viewing the transition to elementary school as an opportune time for families to build fresh, strong connections in the relational dimensions addressed by FAST. We also aimed to recruit at least 60 percent of kindergarten families to participate. Once in the schools, however, we found out that we had set ourselves a very challenging task.

CHALLENGES TO RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION: LESSONS LEARNED FROM PARENT FOCUS GROUPS

Getting families in the door – and keeping them involved until the end of the program – proved much harder than we expected. We never made our 60 percent participation goal; we averaged 22 percent, and that number was achieved through intense and sustained effort.

Did families not attend because word of the program failed to reach them? Did they feel unwelcome in their school? Did violence in neighborhoods pose a threat? What about the families who came only once or twice and never returned?

Yet many families that did participate loved the FAST program. They came to every session they could manage. What made them attend session after session, even after they graduated from the program? Why did the program thrive and gain momentum at some schools but limited traction at others? As a team we came to understand that there are at least two outreach strands to consider. One is recruitment – reaching out to people to extend that first invitation to “come and try” FAST. The other is retention – encouraging and maintaining ongoing attendance. What were we doing right? What were we missing?

Going straight to the parents and guardians was the best way to answer these questions, so we invited parents to focus groups facilitated by AIR in 2015. These focus groups included caregivers from nineteen schools and were among the most illuminating exercises we have done. The forty-three participants fell along the entire spectrum of FAST attendance. They gave us amazing, strategic insights into their situations, decision-making, and perceptions of their schools. Moms, dads, grandmothers, and an uncle clearly identified barriers to participating in their schools – and serving as volunteers – of which we were unaware. They also clarified implementation issues relevant to organization and buy-in. We came away from these groups with a much more nuanced understanding of – and appreciation for – the varied situations faced by the families and schools we are serving.

Building Awareness, Achieving Attendance

Had families heard about the program? Attendees answered with a resounding “Yes.” Parents described FAST program features in remarkable detail, even if they had never attended a FAST session. They knew that the entire family could attend; they would meet other parents; they would have special one-on-one time with their child. In short, awareness of the program was high – far higher than attendance.

Kudos go to Turning Points staff, our SDP partners, FAST teams, and school staff for successfully building awareness. At every school, recruitment is locally driven, so parents recalled different after-school promotional events, variously hosted by teams with school parents, principals, and teachers. Pizza parties with balloons, Rita’s Water Ice treats, school supply giveaways, and more were held over several weeks at all schools. Such events added to a sense of welcome, as one grandmother warmly reflected: “They had a welcome day with water ice and pretzels by the principal, . . . a good experience for my grandson.” In fact, during the second year, we started recruitment during summer, to build awareness and momentum going into the school year. All of these efforts were quite successful in raising awareness. But still, we didn’t achieve the participation we wanted.

Influence of Children and Teachers

What or who seemed to elevate attendance? Kids and teachers inviting parents personally and repeatedly. The children, one mother said, “get you the most response.” She remembered her son coming home from school and saying, “If we go to FAST, we’ll get a pretzel the next day. He really wanted to go. And because I didn’t want him to be left out, we went.” Across our project, we observed this happening. Where teachers talked up FAST repeatedly, kids paid attention. Where activities and rewards excited children, parents responded. Children who fell in love with FAST also nagged parents to return week after week. One mother admitted, “My son made me go back. I did it to keep him happy.”

But FAST was rewarding for parents, too. One participant said she was surprised about its impact on her:

I loved FAST. . . . It helped me to open up, and people gravitated to me. We still hang out together and socialize. I didn’t expect it to do anything for me. I did it for my grandson. But it helped me even more.

Barriers – Logistical and Perceptual

Despite this impact, our attendance goals went unmet. Parents shared how program times conflicted with work schedules, transportation was complicated, and multiple family responsibilities – such as taking care of sick family members – jostled for priority. One mother shared, “I was tired and pregnant and didn’t want to take two busses to go back to school to do the program.”

We tried to adapt program schedules to provide more options for working parents. Instead of meeting right after school pick-up, we scheduled some meetings after 5:30 pm. A few programs were held on Saturdays. These changes required our district partners to reschedule rooms, compromise with custodial staff, and arrange and pay for after-hours security. In addition, such changes required teachers to remain very late or to come to work on Saturday mornings. The results? The alternative times netted no gains.

Many parents said they send their children to schools outside their neighborhoods for a variety of reasons, and transportation to distant schools adds complexity to their lives and also affects how they engage in school activities. Insurance liability restrictions kept agency partners from offering rides, and the project did not have money to help with transportation.

Multiple responsibilities? Working two jobs, homeless, taking care of parents, helping children with homework – where does an after-school family engagement program fit into crowded priority lists?

And then there are parents’ perceptions and sense of welcome at the school. Impressions of staff strengths and competence, sincerity, willingness to reach out, and attentiveness emerged as parents discussed their schools’ various climates. Positive insights balanced concerns. Management styles, the tone of conversations in front of children, and levels of organization came to the fore. A principal at one school, for example, was praised as “assertive” and competent at conflict management. Parents noted principals’ efforts to connect and know children by name. Many also had high praise for their children’s teachers, the way they made them feel welcome, and their efforts to communicate and problem-solve. As one noted, “My son’s teacher would make comments about his day when I picked him up,” and that it made the school “feel welcoming.”

It makes sense that positive experiences fed a sense of welcome; however, even one bad experience, or a personal sense of ambivalence, fed unease. A principal being late for meetings left a mother feeling disrespected. All parents brought up the negative impacts of budget-driven staff cuts on workloads, especially during the budget crisis in 2013 (when our project launched). They noted staff being stretched too thin and resources being too scarce. Teachers being moved to different classrooms after the school year started – and no communications being sent home about the staff turnover – frustrated parents, too. Implicitly, lack of communication was linked to a lack of welcome and a sense of dissonance.

For parents who feel alienated, introducing a family engagement program alongside other school climate improvements that meet families’ expressed needs and desires makes a great deal of sense. Parents might otherwise view the program as irrelevant.

Why Some Families Came but Didn’t Return: Importance of Communication and Trust

What else did our focus groups tell us? First and second impressions are vitally important, but so are third, fourth, and fifth. Consistent, highquality program delivery – and clear communication – earn parents’ respect and trust, with attendant results. Unfortunately, faltering even once can lead to losing parents’ trust.

The focus groups helped us see where we need to strengthen communication. For example, young children (in particular) benefit from routine, so FAST has built-in repetition for some activities. While activity supplies are refreshed and varied weekly, an activity might come to feel rote to parents over time. One mother who returned week after week because her son loved the program reflected, “It would have been more engaging if it could have different activities week to week. Changing it up would keep parents more interested.” Comments like this showed that not all parents had been exposed to the reasons for repetition – or the value of the developmentally appropriate activities. They would have appreciated this information.

In addition, some FAST teams came across as “harried” or “disorganized” if they felt pressed for time – a problem at some schools where custodians insisted on a strict schedule since overtime was unavailable. One parent noted:

At first they ran it by the clock and were very professional, . . . treated us like royalty. By the end it wasn’t run as tightly. There were some staff changes. . . . We left early a few times because it was a bit disorganized.

If a program doesn’t come across as organized, parents will likely feel they are wasting their time, even disrespected: “This is two hours of my time and I have a lot to do at home.” At our January 2016 project planning meeting, two of our i3 project consultants (Rutgers University’s Nancy Boyd-Franklin and AIR’s David Osher) also discussed how disorganization communicates disrespect – the last thing we want to convey to parents.

The issues we’ve identified here are, in part, scale-up issues. We’ve learned it is very important to revisit the basics. Communicating rationales for activities and logistics is an easy-to-miss element of retention. Parents reminded us why we must continually ask for their input, even as we stretch to serve more families at more schools. We also were reminded that our good intentions are irrelevant: good intentions don’t earn trust. We earn trust at every meeting by showing respect for families and staff. We earn trust by always being on time, asking for regular feedback about how the program is working for the school, and following through on received suggestions. While we try to do this, there’s always room for improvement.

Why Some Families Returned Again and Again: Sense of Community and Student Impact

“My kid begged me to take him to FAST.” Another parent said, “Starting FAST made [school] feel more like a family. It helped relationships between parents, like an ice-breaker.” One dad commented, “As a single dad with four kids, . . . FAST helped me so much – to stop being by myself.”

Parents appreciated meeting other families, sharing recipes, networking for jobs, learning about community resources, and spending one-on-one time with their child. Parents also celebrated the behavior changes they observed in their children. One parent discussed how her child’s speech problems improved, another how her child, a picky eater, learned to try new foods. This experience was a huge victory for her child, and she credited a FAST team member for helping. These and other anecdotal stories came out as parents talked, revealing poignant, difficult-to-statistically-describe program impacts.

Building bridges between parents – extending the network – is one of the goals of FAST. How rewarding it was to hear parents reflect on this! Parents also commented on the connections between community building and problem solving.

We all need to get engaged with other parents. If we knew people before problems happen, we can work problems out as parents. But [mostly] we all get to know each other when there’s a problem.

Building Parent Leaders and Refining Recruitment

When parents graduate from FAST, they might decide to become FAST team members for future implementations. Undoubtedly, they are the program’s most credible spokespeople. But it usually takes one or two FAST cycles to graduate prospective parent leaders, which means the first year is developmental within a school. The first year is also key to refining messages and communication channels for recruitment.

FAST recruitment normally depends on face-to-face conversations and home visits, but in Philadelphia, district safety concerns led us to rely mostly on school-based interactions, emails, robo-calls, and the like. We discovered that for some people, though, face-to-face communication makes all the difference in feeling invited. When asked in an informal parent survey about how they preferred to learn about new activities, Latina respondents specifically highlighted face-to-face invitations. Their answers were related through an interpreter who was a FAST team member. We wondered, without this team member who could serve as an interpreter, would these parents still have attended and shared this information with us?

Qualified interpreters, strategically selected message channels, and culturally relevant content and images in messages, events, meals, and literacy are key considerations in recruitment and retention. Clearly, diverse parents and ELL staff (or volunteer interpreters) are critical to involve on teams and in designing outreach. With Philadelphia’s high immigrant population, it’s not surprising that some of our i3 schools are mini–United Nations, which meant that we translated materials (through the district) into Albanian, Arabic, Chinese, French, Khmer, Nepali, Russian, Spanish, and Vietnamese. Since some parents also have lower levels of literacy in their home languages, we also evaluated our materials to assure messages were readable at or below a seventh-grade level.

School parents working on teams also help refine the FAST program for the school culture, as well as help create the messages that resonate with other parents in the community. They are invaluable allies when navigating barriers to program implementation. That said, planners can further strengthen outreach by gathering insights from representatives of as many social groups in the school community as possible. Program advocates might advance this effort by systematically conferring with school staff and community residents with long-term knowledge of the neighborhood. Which families in the school regularly attend meetings or volunteer? Which are on the fringe? Invitations to groups who may sometimes seem relegated to the sidelines need to be specially considered. Who are their de facto opinion leaders? Are there particular people in the school community they really identify with? Because of the importance of this task, it’s worth considering allocating time and money to set up school-based parent advisory panels to specifically inventory and reflect on the nature of school communications, cultures, and family involvement.

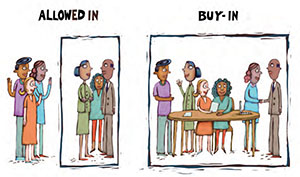

The Crux of Recruitment: “Buy-In” versus “Allowed In”

One of our key lessons is that buy-in is not the same as being “allowed in.” In our i3 project, principals agreed to implement FAST several months before the fall 2013 launch. In the interim – amid contract disputes, staff lay-offs, and reallocations – family engagement was a priority, but so were a lot of other things. As a result, in some schools we were mostly allowed in; the buy-in had to be re-initiated.

Buy-in is, at least partially, related to shared vision. Among the principals involved in the i3 project, some have been very invested in FAST. These principals participated actively in outreach and helped us to problem-solve, even sharing with other principals why they are sold on the program as part of their family engagement efforts. We also came to recognize that some school leaders were more passive in interacting with us and occasionally less than forthcoming in collaborating with us about how to best communicate with parents. This leads us to wonder if the principal’s priorities and vision may not have aligned with those of FAST in ways appropriate for the school. The value and goals of FAST may not have come across clearly, although our district partners tirelessly advocated for us. Or the financial crises impacting the school may have simply raised the height of obstacles on the implementation road.

Developing alignment – a shared understanding of goals on both sides – requires sufficient time for orientation and planning pre-launch. Just as school leaders desire clarity about how a program will serve their goals, program implementers and teams need to know how they can align the program with school goals. Gains made through a program also need to be communicated clearly so that leaders can share in the reward, their vision affirmed and enlarged. Over the longer term, buy-in gives a program time to develop the traction and accrue the gains that lead to that sense of reward. Fortunately, we’ve seen it happen in some schools, offering encouragement about what is possible.

The Impact of District Financial Stress on School-Family Engagement

The schools where we introduced FAST were described in legalese as “low-performing” (based on Annual Yearly Progress results), but we believe a more accurate descriptor is “underresourced.” These schools are bearing the brunt of several years of budget cuts borne by the district as a result of federal- and state-level funding fluctuations. The district has made national headline news because of budget battles between the city and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, who share financial responsibility for the district as well as lopsided policy-making authority. Just before we launched FAST in 2013, the district was forced to lay off 3,783 employees and close twenty-four schools due to a politically disputed budget shortfall (Lyman & Walsh 2013). Principals were filling in as substitute teachers and lunch room monitors and had little time to discuss the program with us. We can’t help but wonder at the impacts of this crisis on school-level buy-in to our program.

Given this context, it might come as no surprise that we use the word “heroic” to describe the work of some of our teacher, principal, family, and district partners. Developing long-term relationships with these folks has elevated our appreciation for the daily demands they face to meet students’ needs, even as they add a new family engagement program to their workload. We have stood in kindergarten classrooms crowded with more than thirty desks, where students work under the smiling gaze of Clifford-the-Big-Red-Dog and colorful banners with good behavior slogans and math facts. Displayed artwork shows each student’s vibrant, imaginative side. Teachers in classrooms we have visited are creating rich learning environments, despite scarce resources.

Many of our focus group members praised their children’s teachers for spending their own money to purchase materials for classrooms. It was sobering to note that several low-income families were likewise contributing to classroom supplies out of their own pocket – to support their teachers and children. With the vast majority of our families living at or far below the poverty line, the school district’s fiscal straits are deeply felt; many families try to fill needs when they can. They worry about their children and their schools, and they are not alone: According to a recent poll, public education tops the list of concerns for the citizens of Philadelphia, above issues such as crime and jobs (The Pew Charitable Trusts 2015). At every focus group, parents expressed how much more they wanted for the city’s children and schools.

FINAL REFLECTIONS

So what does this mean for those of us trying to implement family engagement programs in “low-performing,” under-resourced schools in financially stressed districts? What inroads might family engagement programs make, when civic decks seem circumstantially stacked?

The stories our focus group parents told speak to the reasons we do this work. They also gave us insights into successes we had not heard about before, or counted. As a result, we’ve come to realize that authentic success has a different look than we predicted in our grant proposal to the U.S. Department of Education. Consider this evidence of parents’ growth in agency and sense of connection to their school communities: FAST families collaborated, using their groups’ resources, to purchase Thanksgiving turkeys for food boxes they collected for other low-income families at their schools. Their generosity deeply affected us. How did it affect the recipients and schools?

Nuanced, incremental relationship building; cross-cultural mingling; even bracing moments of mutual encouragement among adults who met through FAST – these encourage and motivate us. If it weren’t for these less obvious forms of success, we might ask, how many teachers would persist in overcrowded classrooms? How many principals would labor the same hours – for 16 percent less pay than they earned the previous year? Seemingly small successes mean a great deal in deeply challenged places.

Through family engagement programs like FAST, we build school-based relationships critical to an agenda of transformation. As much as we want transformation to be dramatic, it is proving to be incremental, with every target school shedding light on what is required to engage families more successfully.

For more on the FAST program, see https://www.familiesandschools.org/.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Kim Jones, i3 project leader at Turning Points for Children, whose life was tragically taken on January 13, 2015. Kim was dedicated to bettering the lives of children and families in Philadelphia. Her work mirrored the respect and hope embedded in FAST.

1 For information on FAST's inclusion on evidence-based lists, see http://www.familiesandschools.org/why-fast-works/evidence-based-lists/.

Lyman, R., and M. W. Walsh. 2013. “Philadelphia Borrows So Its Schools Open On Time,” New York Times (August 15).

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2015. “New Pew Poll: Philadelphians View K–12 Education as Top Issue.”