Strengthening Relationships with Families in the School Community: Do School Leaders Make a Difference?

School principals can play a key role in family engagement by believing in the leadership capacity of parents and viewing families as partners in their school community.

Many family engagement programs logically focus on providing training and support for parent leaders, giving them the skills and knowledge necessary to effectively partner with schools. Yet in implementing family engagement programs, I have found again and again that the key to successful partnerships between families and schools is the school principal. Even with comprehensive parent leadership training, sustainable family engagement initiatives cannot truly take hold without buy-in, shared understanding, and a structure for parent engagement at the school level.

A FOCUS ON CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE PARENT ENGAGEMENT

For over twenty years, I have worked in programs providing parent leadership training to bilingual families in Southern California, first as the director of the  Multifunctional Resource Center (MRC) at the Center for Language Minority Education and Research (CLMER) at California State University, Long Beach, and since 2000, at the California Association for Bilingual Education (CABE). Because we work with parents who are culturally, linguistically, and racially diverse, the sessions are grounded in a “community learning theory” (CLT) approach, developed by Roberto Vargas (2008) and J. David Ramirez (2010), a cultural strategy that uses diversity-responsive processes and activities essential for developing the critical relationships that provide the foundation for individual and community empowerment, action, and change.

Multifunctional Resource Center (MRC) at the Center for Language Minority Education and Research (CLMER) at California State University, Long Beach, and since 2000, at the California Association for Bilingual Education (CABE). Because we work with parents who are culturally, linguistically, and racially diverse, the sessions are grounded in a “community learning theory” (CLT) approach, developed by Roberto Vargas (2008) and J. David Ramirez (2010), a cultural strategy that uses diversity-responsive processes and activities essential for developing the critical relationships that provide the foundation for individual and community empowerment, action, and change.

The CLT approach includes acknowledging and building on existing cultural “funds of knowledge,” or what Yosso (2005) and others call “community cultural wealth.” It also introduces Vargas’s (1987) concepts of the Unity Principle, which seeks to build a sense of conocimiento (“Who am I?” “Who is s/he?” and “Who are we?”) and unity through shared power and trust. Using this process, we learn about each person and the lived experiences that have given them cultural capital and wisdom that is now shared with others. Knowing individuals at a deeper level brings confianza (confidence and trust) to work together in unity and power. In his work in communities, Vargas (2013) has also introduced us to the concept of “co-powerment,” a practice that he believes is:

more collaborative than the hierarchical relationships often implied by the idea of empowerment. . . . Co-powerment is communication that seeks to lift the confidence, energy, and agency of another person, self, and the relationship. It is lifting the power of self and others. The better we become at co-powering, the more we grow deeper relationships that develop our power to create positive personal, family, and community change.

When we used this culturally responsive process, we were inspired by the transformation experienced by the parents attending our institutes – especially after they had attended several sessions. Parents who never shared or participated in the early discussions would freely and confidently do so during the final sessions; parents shared that they were more active in ensuring their child was getting on track for college. We were creating and fostering a sense of community, belonging, and personal power among the parents attending the sessions. Project staff developed a greater understanding of the families and became more adept at addressing the cultural, linguistic, social, economic, and political barriers they faced. They created activities that engaged parents through the use of art and metaphors, creating a safe place to share their lives and aspirations for their children. The parents recognized that we were reaching out to them in a very different way than schools usually did.

SCHOOL-LEVEL BARRIERS TO PARENT ENGAGEMENT

When I became the chief executive officer of CABE in 2000, we continued to offer the parent institutes, as well as a parent center, at our annual conference. As the CEO, I often ran into “transformed” parents who had previously attended our institutes. Many of them were frustrated and in some cases “militant” because they were going back to schools that were not transformed. Schools did not honor the role that parents can play in schools and share an understanding that parents are their children’s first teachers. Some parents had learned that the school budget required approval of the school site council, but their school only asked them to sign the budget without the opportunity to review or comment on it. The knowledge and skills they learned in our earlier institutes were not deep enough to work through the barriers created in some schools that were not prepared to “engage” parents in a meaningful and partnering way.

As an organization that advocates for equitable programs for English learners and their families, CABE firmly believes that families are a child’s first teacher, and that they have the capacity to be strong partners with schools (Dantas & Manyak 2011). Being in a leadership role and with a deep commitment to engaging families and parents, I was searching for a way to, at minimum, lessen the frustration felt by parents who could not make inroads into their children’s schools.

In 2003, my colleagues and I submitted a proposal for a Parent Information Resource Center (PIRC) grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Innovation and Improvement. We were successful in obtaining the grant funds, and we were on our way to search for the best way to serve our parent communities. In 2006, CABE secured a second PIRC grant – this one with a statewide focus – to further develop our parent engagement program. Since this federal grant included funding to conduct research on family engagement, we had the opportunity to not only design a culturally responsive program for communities of color, but to also really look into the impact the program was having on parents and their children’s academic achievement. Eighteen treatment schools and eighteen control schools were randomly selected to participate in this study.

During the first year, we developed a three-level curriculum. The control schools did not receive any of the seesions that were provided in the treatment schools. Parents at the eighteen treatment schools received twelve three-hour modules at the Mastery level and eighteen three-hour modules for the trainer-of-trainers Expert level, both rooted in the CLT approach. Because of our experience with previous programs, we wanted to create a program where, at the end of the study, the schools would be left with “parent experts” who had the capacity to maintain the program at the conclusion of the grant. We had also learned that when families from the same school work together, they form supportive social relationships that can provide a protective function for families who face many challenges (Ramirez 2010; Yosso 2005; Henderson et al. 2007). This is especially true for immigrant families, who often lack the support of extended families and feel they are isolated in their communities.

The basic research question was, “Did the students whose parents attended the Mastery and Expert level sessions have an increase in achievement?” Our study showed that they did have significant growth over other students at the treatment and control schools. Another surprising result was that English learners whose parents attended the parent leadership development sessions also learned more English than students at the treatment schools whose parents hadn’t attended the program sessions, as measured by the gains on the California English Language Development Test.

Despite these gains, we once again found a key ingredient to be missing from the program: the school leader. While the principals were pleased with the outcomes for parents, they did not fully understand – nor did we make provisions for working specifically on – the knowledge and skills of the school leader that are necessary to engage the families at the school and to forge those important relationships. There were “bright spots” in about half of the eighteen schools, where the principals saw the power of having parents “join the team.” The principals at these schools1 shared, during individual interviews, the changes they saw in the parents at their school. They spoke of how the parents were “changing the dynamics” of teacher-to-parent interactions, and that parents had learned how to communicate effectively with them, so they were able to express their views about what changes were needed at the school. However, the research project was not designed to collect survey information to document these changes.

PREPARING SCHOOL LEADERS AND STAFF FOR FAMILY ENGAGEMENT

When we secured a federal Investing in Innovation (i3) Development grant in 2012 to study parental engagement, we were able to put all of our previous learning to the task. We have laid a strong foundation for the program by making sure that our previous shortcomings in designing a program for engaging parents were carefully considered. The i3 Project 2INSPIRE Family, School & Community Engagement Program now includes professional learning for everyone at the school; a strong emphasis on fostering relationships among the principal, teachers, and other parents; and the development of a yearly plan for parental engagement where parents help plan, monitor, and evaluate the plan, and where parent leadership development is only one of the components – not the total program.

The new program, which involves ten schools at three districts in southern California, offers professional development for school leaders, teachers, office support staff, and parents. The school leader and district representatives have attended a two-day session on parent engagement research, strategies, and practices and a two-day session on cultural proficiency in schools by noted experts (Michelle Brooks, Karen Mapp, and Randall Lindsay). They also have attended a two-day session on the Action Team for Partnerships (ATP) model led by Joyce Epstein and have written their action plan for parental engagement for their school (Epstein et al. 2002). In our previous attempts at designing programs for parents, we learned that unless there is a structure and shared understandings as to how to engage parents at the school level, the likelihood of sustaining the program is minimized.

We also felt it was important to provide teachers with sessions on building relationships with families, so every year we have Roberto Vargas facilitate a seminar introducing CLT to teachers participating in our program. During our spring 2015 meeting with district and school leaders, teachers suggested that office staff, and even our parent leaders, could benefit from attending alongside the teachers in learning how to build relationships. Therefore, school teams attended our October 2015 CLT session, which proved to be very effective, giving teachers, office staff, and parents the opportunity to learn about each other and form vital relationships. Project staff reported that after this session, they felt the climate at the school was much more inviting. A principal at one of the i3 schools also reported that an amazing thing had happened: an especially irate parent, who had a two-year battle with a teacher, had apologized to the teacher and pledged to work on their relationship.

Teachers are also improving their perceptions of parents. In the first i3 survey of teachers, 55 percent of classroom teachers said they felt that their students’ parents helped their children learn. In Year 2, 78 percent of school staff indicated that parents at their school who are actively engaged have a positive impact on student learning, and by Year 3, that number had increased to 88 percent of school staff. The i3 research project is documenting all of these activities and changes in the schools.

LESSONS LEARNED

The i3 Project 2INSPIRE schools are working with families to forge those important relationships and partnerships needed for school and student success. The concepts and outcomes presented in the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family School Partnerships (Mapp & Kuttner 2013) are becoming evident in actual practices of the program.

Because of the strength-based, collaborative leadership development program that provides families the necessary tools to participate more fully in the education of their children, school leaders are recognizing that parent leadership is important. On a yearly survey given at the beginning of each school year, principal responses have steadily increased on a survey item that asks them whether this description applies to their school: “Families and staff have opportunities to learn together how to collaborate to improve student achievement.” Out of the ten principals participating in our program, in Year 1, three indicated that this statement was “a great deal or a lot like our school”; in Year 2, it was five principals; and in Year 3, it was eight principals.

School leaders are recognizing the positive benefits of having a critical mass of parent leaders who work as a team and have reached out to them to form a stronger relationship, which has really added value to their schools. For example, one principal reported that the parents came to her to tell of their concern that the library was closed and not available for the children. The principal explained that she did not have the funds to pay for someone to reorganize the books into the new reading levels. The parents stepped up and worked as a team, and the library was available two months later.

Events like these are happening even in schools with a large number of families with racially, ethnically, and economically diverse backgrounds. In at least seven of the ten schools, the parents have developed the skills, knowledge, and confidence needed to negotiate the multiple roles – supporters, encouragers, monitors, decision-makers, advocates, collaborators – of effective family engagement (Mapp & Kuttner 2013). District staff, school leaders, teachers, and other school staff are learning that given relevant information about schools, families can participate fully in school activities and functions. Schools are learning to respect and honor families’ existing knowledge and their potential contributions to the work of schools. As one principal participating in our i3 initiative said:

At their LCAP2 parent meetings, parents and community members had a chance to receive an update on the school’s goals and performance and to voice their ideas about how they could further support students in their academic growth and overall well-being at the school. Parents attending had the chance to collaborate in small groups and chart their ideas under each of the three LCAP goals: Teaching and Learning, Enrichment and School Climate, and Safety. Each small group of parents had a facilitator that supported them in sharing their ideas. Many of the facilitators were other parents who participated in the Project 2INSPIRE parent leadership development classes.

These parents are now leaders on the campus, creating positive change and supporting our students in many roles, including being members of our School Site Council and English Learner Advisory Committee. The conversations consisted of high-quality, informed ideas and empowered all involved to make Martin Elementary the best it can be. The school doesn’t belong to any one person or any one group – Martin Elementary belongs to all of us whose children study here and all who work at the school to teach the children.

Measuring Principal Support for Parent Leadership

One thing all of our schools have learned is that engaging families is a process, and the first step is to demonstrate a commitment to family engagement as a core strategy to improve teaching and learning, as Jeynes (2011) states: “A school can run a parental engagement program with great efficiency, but parents can easily discern whether their participation is welcome and whether their input is warmly received.”

One of the measures we use to document progress in working with the schools is feedback about the program from the parent specialists who provide the parent leadership sessions at the schools every week. In these parent leaders’ responses to the question of rating the principal’s support for the program (1=strong, 2=supportive, 3=developing and 4=weak), they reported that five of the ten principals in the i3 project are “strong” supporters and are effectively engaging their families, two of the school leaders are “supportive,” and three others are “developing” their skills.

The principals identified as strong supporters are realizing that, as school leaders, they also have the skills, knowledge, and confidence to create welcoming and inviting learning communities for their families and parents. For example, as part of an assignment in the Expert level training, parents are asked to make presentations to the teachers at a staff meeting. At two schools with principals who are “strong” supporters, principals not only encouraged their parent leaders to present what they were learning to the teachers, but they worked alongside the parent specialist to prepare a parent team from each of the four i3 schools in the district to make a presentation to the school board about the i3 Project 2INSPIRE program. These two principals attended the district meeting along with the parents and spoke of how proud they were of the parents at their school. When one of the principals was transferred to a new school, some of the parent leaders from her previous school “transferred” with her.

On the other hand, the three school leaders who are “developing” seem to see many barriers to the engagement of parents at their school. In an individual interview, one of these principals told us that the parents at their school “just won’t do those types of activities,” referring to the presentations for teachers at staff meetings. In discussing the fact that our program’s “expert and advanced” parent leaders facilitate the parent leadership development sessions for other parents, one of the “developing” principals stated, “I am not sure if the parents at my school can ever manage being a facilitator and present the technical information we cover in the modules after they graduate from our Expert level.” It was interesting for me to hear this comment, because three of the four parent specialists who work with the i3 project schools are actually parent leaders from our former PIRC project, serving as proof that parents can rise to high levels when given the chance. In fact, parents at this principals’ school have demonstrated their leadership abilities in other ways, creating an Earth Day event for the kindergarten classes and making project t-shirts.

At another school with a “developing” principal, parents report that they continue to feel like they are on the “outside” of the school; the principal has parents at her school busy with tasks, but when it comes to deciding what happens at that school, the parents do not have a voice. This principal completed the school’s ATP plan on her own, without bringing in the parent leaders who attended the ATP session with Joyce Epstein. The parents do not feel that they can have a relationship that is based on mutual respect at this school. In her study of school leadership and family engagement, Auerbach (2009) reports that many principals “named ‘relationship building’ as part of their vision of parent involvement, but few could be observed actually engaging in it with parents.”

Parent Involvement vs. Parent Engagement

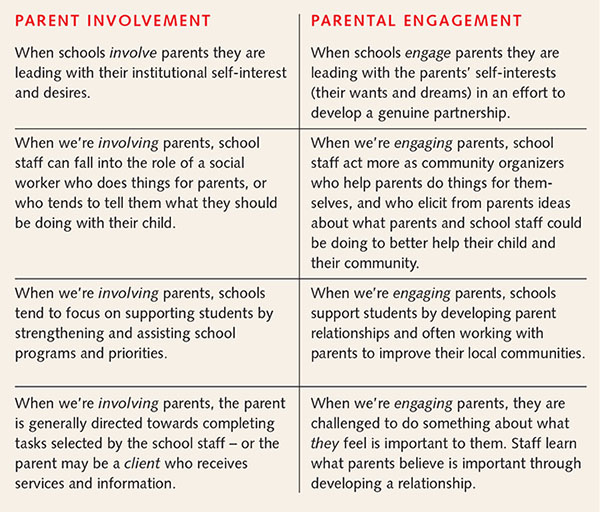

Mapp (2010) talks about a paradigm shift that is needed to redefine what it means to engage parents, and Ferlazzo (2009) outlines important distinctions in the way families become partners in the school, describing the differences between involvement and engagement:

When we’re engaging parents, the parent is considered a leader or a potential leader who is integral to identifying a vision and goals. He/she encourages others to contribute their own vision to that big picture and helps perform the tasks that need to be achieved in order to reach those goals.

The following matrix is an adaptation of his main points. It gives us a way to see the differences more clearly and then compare the engagement features found in our schools between “strong” principals and those who are “developing” their skills to fully engage the parents at their school.

PARENT INVOLVEMENT | PARENTAL ENGAGEMENT

In looking at the dynamics of the i3 schools, it seems that those five principals considered “strong” supporters have begun to make that paradigm shift from involvement to engagement as Ferlazzo describes. They see parents as leaders and have given them the space to use their newly developed skills as parent leaders. These principals tell us that their parents are transformed and have seen that their support and the relationship they developed with them over the last two years is making a difference.

The “developing” principals, while they are reporting that they have a relationship with parents, seem to be operating in the old paradigm of “involving” parents. These principals are providing more services to parents and offering them opportunities, such as “coffee with the principal,” to dialog with them or introduce topics they want to share with parents. Although they have the best intentions for the parents at their school, they have not shifted their perspective about what parents are capable of doing. This diminishes the role parents have in their school community.

Confidence in Relationship Building and Belief in Parent Capacity

For school leaders, building relationships with parents is not an easy task. It takes nurturing and persistence in order to develop and gain trust with the families in the school community, yet these relationships are of the utmost importance (Cunningham, Kreider & Ocón 2012). Strong family, school, and community engagement programs reach out to families and engage them in true partnerships, challenging parents to learn and apply the necessary supports for their children’s learning at home or school. It is a shared-responsibility, integrated, sustained, and family-strengthening approach that truly engages parents and fosters the relationships between schools and the home. We see this in schools when the school leader is confident in developing relationships with the families in the school.

What is becoming evident in our work is that families who have participated in the i3 Parent Leadership Development Program have the tools they need to feel connected to the school, understand how the school functions, and participate in the school more readily. The missing link in some schools is for school leaders to truly believe that parents – especially those who have taken on the challenge of becoming parent leaders – are an asset to the school.

In the i3 project we have seen shifts in principals’ perceptions of parents. It usually comes about when there is an event at the school where parents have taken the lead and carry out the event in a very professional manner and with great results. This then triggers a change in the perception and they begin to trust that parents have the ability and knowledge. This success also leads to a measureable change in the principals’ own confidence to let this happen. Those school leaders who recognize that parents are assets and resources for their school will see their schools change and become better, and as a result, will see a positive impact on student learning and well-being.

1 Part of the criteria used in the selection of the schools in the 2006–2011 study were what we called “readiness factors” for parental engagement. We felt it was important to have schools that were not dealing with many other challenges and could participate fully in the program.

2 Local Control Accountability Plans (LCAPs) are part of California’s new local control funding formula, which dictates that districts obtain input from parents and the community on their school plans.

Auerbach, S. 2009. “Walking the Walk: Portraits in Leadership for Family Engagement in Urban Schools,” The School Community Journal 19, no. 1:9–32.

Cunningham, S., H. Kreider, and J. Ocón, J. 2012. “Influence of a Parent Leadership Program on Participants’ Leadership Capacity and Actions,” School Community Journal 22, no.1:111–124.

Dantas, M., and P. Manyak. 2011. Home-School Connections in a Multicultural Society: Learning from and with Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Families. New York: Routledge.

Epstein, J., M. Sanders, B. Simon, K. Salinas, N. Jansorn, and F. VanVoorhis. 2002. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Washington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

Ferlazzo, L. 2009. “Parent Involvement or Parent Engagement,” Learning First Alliance blog (May 19).

Henderson, A., K. Mapp, V. Johnson, and D. Davies. 2007. Beyond the Bake Sale: The Essential Guide to Family-School Partnerships. New York: The New Press.

Jeynes, W. 2011. “Parental Involvement Research: Moving to the Next Level,” The School Community Journal 21, no. 1:9–18.

Mapp, K. L., and P. J. Kuttner. 2013. Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity- Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships. Austin, TX: Southern Educational Development Laboratory.

Mapp, K. L. 2010. “Setting the Stage: Reframing Family and Community Engagement,” address given at the National Policy Forum for Family, School and Community Engagement (November 9), Washington, DC.

Ramirez, J. D. 2010. “Building Family Support for Student Achievement: CABE Project INSPIRE Parent Leadership Development Program,” The Multilingual Educator (March).

Vargas, R. 2013. “Co-powerment,” Rockwood Leadership Institute blog (January 10).

Vargas, R. 2008. Family Activism: Empowering Your Community, Beginning with Family and Friends. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Vargas, R. 1987. “Transformative Knowledge: A Chicano Perspective,” In Context, A Quarterly of Humane Sustainable Culture 17:48–53.

Yosso, T. 2005. “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth,” Race, Ethnicity and Education 8, no. 1:169–91.