Making Space for Collaboration and Leadership: The Role of Program Staff in Successful Family Engagement Initiatives

Parent engagement coordinators provide the foundation for family engagement by modeling shared leadership, facilitating trust, and creating space to build partnerships with parents and schools.

Since 1992, The Children’s Aid Society (CAS) has partnered with the New York City Department of Education, schools, and the community to provide resources and supports to students and their families using our community school model. The Washington Heights community schools have engaged in groundbreaking work with  parents and the community in developing parent leaders for more than twenty years. Four key elements serve as the foundation of the Children’s Aid approach to parent engagement and the development of parent leaders: parent resource centers, parent engagement coordinators, adult education classes, and leadership development.

parents and the community in developing parent leaders for more than twenty years. Four key elements serve as the foundation of the Children’s Aid approach to parent engagement and the development of parent leaders: parent resource centers, parent engagement coordinators, adult education classes, and leadership development.

In 2014, Children’s Aid was awarded a federal Investing in Innovation (i3) grant to expand the parent engagement work we had developed in Washington Heights into four schools – from pre-K to grade 12 – in the South Bronx. In our work, we have found that the success of parent engagement initiatives, particularly with a short-term grant such as the i3, depends heavily on the skills of parent engagement coordinators and the engagement levels of the school staff. Offering training, preparation, and support for parent engagement coordinators allows them to model collaborative leadership, value the voices of parents, and create space for building partnerships with parents within school communities.

Implementation of the South Bronx expansion began with the 2014-2015 school year. Our Family Success Network – a team consisting of four parent engagement coordinators and me, the i3 project director – spent the summer of 2014 preparing to begin our work with a full schedule of professional development, classes, and readings. In hiring our parent engagement coordinators, we required candidates to have experience providing services and supports in the South Bronx, and we gave preference to those who lived and/or were raised in the community, allowing them to connect immediately with the community and understand the perspective of parents and residents of the South Bronx. Three of the four coordinators are bilingual – a critical skill because of the large Spanish-speaking populations on our four campuses. We also spent a significant amount of time reading about community schools and how they function, which included both the positive and sometime negative experiences of partnering with a school as an external provider. These conversations made the coordinators very aware of their surroundings, much more attuned to the interactions they have with our partners, and able to identify potential pitfalls and plan around them.

On our first day of school, we started engaging parents while simultaneously building understanding of our role with partners, teachers, and administrators. We would spend time during school drop-off and pick-up sharing fliers about upcoming events for the school year. We developed “community builders,” typically a fun event that allows parents and school staff an opportunity to come together: movie nights, Halloween costume making, family game night, and a holiday dinner. Community builders welcome parents into the school environment and give the school staff an opportunity to develop relationships with families. During that first school year, we were able to engage a total of 878 out of 3,381 parents in a workshop, class, or volunteer experience. Parent participation across the four campuses ranges widely, from 27 to 83 percent. Although the campuses are in different places in their ability as a community to engage parents, the foundation of quality parent engagement is present at all of them.

Replicating the Washington Heights model required more than just providing the key elements on each campus. During our summer of learning, the Family Success Network spent time in Washington Heights learning more about implementation and developing our vision for the South Bronx. As the project director, my role is not only to develop systems and supports to promote intentional parent engagement but also to create an environment where the parent engagement coordinators understand the importance of reflection in the practice of engaging a community. We operate with the understanding that good engagement begins with ourselves and how we model partnership.

As we engage these new communities, our path to partnership requires much more precision and flexibility than just the implementation of the four elements. It requires spending quality time engaging parents in a meaningful way while being willing to learn how to improve practice. We must also understand what parents are interested in learning and what skill sets they would like to expand. We found that many parents were interested in adult education such as GED and English classes, and that parents also enjoy learning more about preparing healthier versions of their menus. These adult education pursuits allow parents to learn and grow, gaining the confidence and voice to actively engage in their children’s school. Valuing parent-focused supports while supporting student academic progress is the balance we like to strike.

The Family Success Network identified a platform for successful parent engagement based on the principles of shared leadership, space, cultural competence, advocacy, and trust. This platform creates the environment and shared understanding for parents to feel valued by the school community while working with school staff to support the academic goals of both their students and the community. This goes well beyond offering events to engage parents in what their child is learning. It extends to empowering and partnering with parents as critical stakeholders in school-wide gains.

MODELING SHARED LEADERSHIP

Establishing parent leaders is central to the work of parent engagement, and as newcomers to this work on our campuses we were very thoughtful about our introduction. The priorities during summer training were to prepare the team of parent engagement coordinators to enter a new community and to identify and train parent leaders. As a team, it is our responsibility to ensure that our team motto – “teamwork makes the dream work” – becomes a reality.

Developing a culture of shared decision- making was the first step to preparing the parent engagement coordinators to lead on their campus. The best way to establish a culture is not only by being specific about expectations and values but, most importantly, modeling shared leadership. Parent engagement coordinators may enter communities with stakeholders who are nervous about parent engagement or skeptical about parents’ roles as critical partners to academic improvement. It is critical that the parent engagement team operate with unwavering commitment to and belief in parents.

Since parent engagement coordinators are leaders in the promotion of family engagement for the campus, involving them in decisions about the program direction has become a way to model responsive leadership. Their ability to value constructive criticism and differing opinions takes practice; in our early trainings we talked at length about the various ways we may receive constructive criticism. We see these moments as opportunities to improve our practice and strengthen our understanding of parent needs and interests.

As members of the Bronx community and parents themselves, the coordinators’ insight is key to keeping the program relevant and receptive to all the skills and talents that parents bring to their leadership roles. This shared leadership practice has allowed the parent engagement coordinators to lead in various ways on behalf of the program and offers them a model of how to field parent input and feel empowered by parent voice. As their confidence blossoms and as they grow into the role, the coordinators’ comfort and confidence with shared decision-making is a team strength. As a team, they look to identify their differing skills to allow one another to lead in their area of strength. For example, one coordinator has a talent in developing workshop presentations. Because of her phenomenal ability to take critical information and turn it into an engaging visual experience, she has played a key role in our conversations as we develop and expand our workshops for parents and share information about our program to our community of stakeholders.

Committing to these operating principles has provided a model for collaborative leadership and decision-making. It also increases the parent engagement coordinators’ abilities to hear parent feedback and see it as the fuel that will allow parents to lead. Often those tough conversations uncover the changes we need for academic improvements. When parents are offering constructive criticism about school or our practices, we are comfortable about asking the important follow-up question: “What do you think would make it better?”

CREATING SPACE FOR PARENT ENGAGEMENT AND LEADERSHIP

Having a safe space for parents to learn, share, and create a parent community is vital to developing parent leaders. Identifying a parent-owned space on the campus also helps to build strong school and community ties, and creating a parent resource center sends a strong message of dedication and commitment to parents. Yet because space in schools is always at a premium, it is a struggle to balance the needs of students and adults, and dedicating a space for parents is a tough ask for most schools.

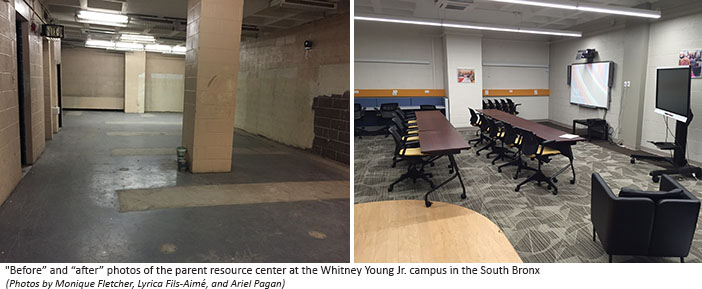

The new parent resource center on the Whitney Young Jr. campus, which includes three schools ranging from pre-K to eighth grade, is a great model for repurposing unused facilities to develop a welcoming space that promotes parent learning and engagement. Utilizing i3 grant funds, we were able to turn the school’s unused locker room into the parent resource center. It took removing the old lockers, painting, and adding lighting, tables, chairs, a couch, and a smartboard to turn the abandoned locker room into a flagship parent resource center that offers classes, workshops, and leadership training to parents in a safe space. The center’s computers also give parents access to technology that improves that learning experience. Along with the common space, the parent resource center also includes the office of the parent engagement coordinator, who serves as a supportive resource to parents in need and ensures that a variety of parent initiatives are offered.

The space also offers a starting place for parent engagement for school staff, where coordinators partner with individual teachers, life coaches, guidance counselors, grade-level teams, and principals to plan and support activities that promote parent engagement. For example, a team of second grade teachers was interested in developing strategies to increase their contacts with parents. After the team reached out to the parent engagement coordinator by visiting the parent resource center, the coordinator attended the next grade-level team meeting and worked with the team to develop their interests and ideas. The team began with a Halloween costume– making event that allowed families a creative and less expensive alternative to store-bought costumes. This hands-on community-building event provided an opportunity for parents, teachers, and staff to support their students’ creations and gave teachers a platform to meet their families while enjoying a fun evening of laughs and creativity. It is this consistent, collaborative, and team-oriented approach that sets the tone and displays the program culture of the Family Success Network.

SOUTH BRONX PARENT VOICES: THE ROLE OF A PARENT RESOURCE CENTER

What do you like most about the space?

“It’s really nice having a space that’s available to the parents. It’s also nice meeting new parents from other schools. I enjoy having a place to have workshops and our PTA meetings.” —Rondell

“It’s nice having so much space for us parents and a place where we have a kitchen and can use computers. It’s always nice to be thought of and be given a new updated room.” —Melissa

What would you say to other parents at other schools that don’t have a parent resource center?

“All parents need a space in our schools. A space where we can learn and have our own classes and where we can have a voice.” —Rondell

“It’s needed! Try to fight for a place. Parent engagement can’t happen in a place that you don’t own. It’s nice having a space that’s safe.” —Melissa

FOSTERING CULTURAL COMPETENCE

We understand the hard work necessary to ensure that all parents feel welcome and have access to ways of strengthening the home and school connection. It is essential that all students, regardless of their differences, are successful academically, and the same understanding is shared in our work with parents. This requires the team to be very thoughtful about four components of cultural competence: awareness of one’s own culture, attitude towards cultural differences, knowledge of different cultural practices and worldviews, and cross-cultural skills (Martin & Vaughn 2010).

The South Bronx has a growing population, especially with respect to residents new to this country. Currently, the four campuses are 72 percent Hispanic and 26 percent Black, but these statistics do not reflect the vast diversity within those two groups. There is also a large Spanish-speaking community that is more prominent on some campuses than others. We operate with the understanding that the most culturally competent team member is the one who is always in a place of learning. This allows us to let parents take the lead in making decisions around the timing, music, food, and agenda for parent engagement events.

For example, one partner school has seen a rapid increase in the African student population. After several incidents of bullying of the African students in regards to Ebola, the school became aware that their connection with the African parent community was limited, so the school’s life-coach team partnered with the Family Success Network to increase the engagement and address the needs of African families. The staff was faced with the challenge of engaging and supporting a community that did not seem to respond to the school’s traditional mechanisms of parent engagement, which included flyers posted around the school campus, flyers sent home in book bags, and the parent engagement coordinator’s direct outreach to parents. The first step in attempting alternative forms of engagement was creating a welcoming space – both symbolically, in the broader school environment, and physically, in the form of the parent resource center itself – for families and staff to build community.

The team decided to hold an event celebrating the various African cultures represented in the school community. The life coaches and the parent engagement coordinator held several focus groups in the parent resource center to ask parents about their interests, needs, perspectives on the school, and what was needed for school improvement. The team utilized the life coach’s contacts to do individual outreach to parents who had already had contact with the school, and they encouraged those parents to reach out to other African parents they knew. This parent-to-parent outreach proved to be the most effective strategy, as the connection and trust that already existed between members of that community helped the other parents feel more comfortable to attend.

Not only did the focus groups offer an opportunity for parents to provide leadership, but they served as great community builders. The school team learned that the parents were very pleased with their children’s school experiences and would like to see some additional tutoring to support academic achievement. The parents were also able to talk more about their cultures and what they would like to see at the first “Celebrate Africa” event.

Once engaged, the parents from the focus groups took on leadership roles to make the event happen. They made decisions about food, recruited other parents by phone, and participated in and led other campus-wide recruitment efforts. The priority of this event was to celebrate the different African countries represented on the campus. The parent resource center was decorated with African flags, and one of the first activities involved the children identifying their home country on the map of Africa, with assistance from their parents.

As a result of the first annual Celebrate Africa event, the community began to unite. There were more than 150 attendees, including members of thirty-three families. The parent resource center buzzed with excitement. The aroma of African food was in the air, and the families wore their traditional African clothing. We learned that the majority of families are from West Africa, with many from Guinea and Mali. Parents, teachers, and students ate and mingled as they laughed and enjoyed the festive environment. Two fathers played the drums while mothers danced. They were proud to show their school appreciation and cultural traditions as they cheered each other on. The families connected with one another and met other families from their home country. It was a transformational experience for all as we were able to watch a new community grow.

By bringing parents into the planning process and executing their suggestions, both through Celebrate Africa and in response to their identified needs, we have seen measurable results in the community’s engagement. There has been a marked increase in the participation from the African community in parent classes, workshops, and volunteer opportunities. Being willing to acknowledge parents as experts in their culture promotes culturally responsive practice and allows parents to take the lead in teaching the team.

PREPARING PARENTS FOR ADVOCACY

Once a culture of shared leadership has been established, parent leaders themselves serve as important models to show the entire community how powerful parents can be. Developing parent leaders to be active members of the community through volunteering and advocacy requires not only a commitment to parents expanding their knowledge but also opportunities for parents to exercise their advocacy skills. The Children’s Aid Ambassadors Program trains youth and parents in advocacy strategies. The advocacy training – provided by Children’s Aid marketing, communications, and public policy staff – consists of topics such as how local, state, and federal policies are set; effective messaging; social media; and “telling your story.” After the training, the ambassadors agree to be available to speak to the press and/or elected officials to share their stories and identify issues that need to be addressed in the community. Having structures and supports to provide parents an avenue through which to advocate and let their voices be heard is vital.

During spring 2015, the Ambassador Program – in partnership with the Family Success Network – trained over thirty parents. One of the parents in attendance at the training was Nancy Maxwell, an active parent from the Whitney Young Jr. campus. Several weeks after the training, Children’s Aid reached out to Nancy in response to a budget released by New York City mayor Bill de Blasio that reneged on a promise to fund summer programming for middle school students. Children’s Aid faced losing summer camp slots for more than 400 young people, and across the city as many as 35,000 students would spend their summer without summer camps and activities. Along with other parents and staff from a coalition of youth-serving organizations, Nancy participated in a rally on the steps of City Hall. Nancy stepped to the podium to push the mayor to fix this mistake immediately. Later that evening, the mayor restored the 35,000 summer camp slots across the city.

This powerful experience for our parents is the key to keeping parents excited and passionate about their potential for changing their community. Not only did one of our parents play a key role in advocating for change, but all the parents were able to see how important and effective their voices can be in provoking change.

HELPING TO BUILD TRUST BETWEEN PARENTS AND SCHOOLS

With the pillars of space, cultural competency, leadership, and advocacy, the foundation for successful implementation of parent engagement is trust. It requires trust from all stakeholders to facilitate the home-to-school connection. Trust involves the willingness to be vulnerable based on the belief that the other party is benevolent, reliable, competent, honest, and open (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy 2000). Working to earn the trust of parents, teachers, students, and administrators is an ongoing priority, requiring us to partner in a way that is transparent and has a clear focus on promoting academic improvement. Our ability to connect and honor parent voice feeds the efficiency in relationship and community building. Partnering with parents about their interests, thoughts, celebrations, and struggles allows us to develop a relationship of mutual respect, honor, and trust.

Getting to a place of trust is not an easy process and is often the most difficult part of bringing a parent engagement initiative to scale. School culture plays an important role in how quickly stakeholders can move to a place of trust. Some schools – even those with very strong parent leadership – struggle to bridge the gap of trust with parents, while parent engagement coordinators find more success (see sidebar).

SOUTH BRONX PARENT VOICES: SCHOOLS WITH A LACK OF TRUST

“Parents feel unsafe when it comes to their children. School staff feel social services needs to be called against parents. It’s not all staff, it’s some staff. Teachers put the blame on the parent. The first question that shouldn’t come out is, What’s going on in the home? That automatically gives a parent a blockage of trust. It makes them feel like teachers are trying to pin issues and concerns within the home.” —Arelis

“Parents need to feel safe with whoever they are talking to about their kids. There is always going to be that fear of saying the wrong thing and they will try to do whatever to take away your children. A lot of parents don’t feel safe going to school to get the help that they need. But the parent and parent engagement coordinator have already built a relationship. There is trust there. I can let loose. I don’t have to watch what I say.” —Reggie

Partnering with parents may come easily to us, but some of the most challenging work for our team can be helping to bring the teachers and parents to a place of partnership. Developing a partnership with school administration can provide an opportunity for systemic influence. For example, before the first parent-teacher conference of the school year, one principal requested parent engagement training for the entire school staff. This afforded us an opportunity to help them understand how hard it is to make sense of words such as “literacy” and phrases such as “deep dive” for people whose first language is not English. This simulation training asked teaching teams to unpack a series of loaded words and phrases so they are easy for parents to understand. Teachers found the training to be eye opening, and several reported changing parts of their presentation so they are easier for everyone to comprehend.

Providing this kind of professional development to school staff helped them expand their understanding of the nuances of responsive parent engagement, see success in increasing parent engagement, and identify potential pitfalls.

BUILDING A COMMUNITY OF LEARNERS

We continue to learn more about our community of parents and how that engagement will influence academic outcomes. Implementing shared decision-making and leadership requires trust in the group’s ability to focus and make informed decisions. Providing a safe space to learn and build community allows parents to feel welcome and valued in the school and is a first step to building partnerships with parents.

If our definition of trust involves a willingness to be vulnerable, then actively working to partner with new parents puts us in a place of constant discomfort in our practice and gives us the motivation to keep fine-tuning our work and reaching new stakeholders. Our challenge is to strike a balance. We need to embrace vulnerability and discomfort enough to push the practice and see real results, but without discouraging our partners. In fact, we need to encourage our partners to embrace the discomfort required for trust to be established.

On several campuses, working to bridge the trust between parents and teachers has become our priority. We have a lot of work to do to meet the goal set by the team: engaging 80 percent of the parents across four campuses. This ambitious goal is a reflection of the team’s willingness to stretch into success and their dedication to excellence in engagement.

Building a successful family engagement initiative must involve setting the groundwork for the parent engagement coordinators to build their practice and develop the skills to foster partnerships and a culture of shared leadership in the school. This will prepare parent engagement coordinators and parents to understand the often-difficult process of moving a school community to trust and partnership on behalf of student well-being and success.

Martin, M., and B. Vaughn. 2010. “Cultural Competence: The Nuts & Bolts of Diversity and Inclusion,” Diversity Officer Magazine (25 October).

Tschannen-Moran, M., and W. K. Hoy. 2000. “A Multidisciplinary Analysis of the Nature, Meaning, and Measurement of Trust,” Review of Educational Research 71:547–593.